Twists of Fate — 50 Years After “Blonde on Blonde,” Bob Dylan Picks Up Some Fallen Angels

By Stuart Mitchner

The girl from L.A. had just arrived in Venice and was sitting at a cafe on Piazza San Marco being hassled by a Yugoslavian when she noticed a bedraggled individual shuffling across the great space, probably on his way to the American Express office to check for mail. His hair was long and scraggly and his jeans were baggy and halfway falling down, as if he had recently lost a great deal of weight. For the better part of a year she’d been exchanging letters with a guy she’d met in Berkeley; they had arranged to meet at the foot of the campanile on the evening of June 21. She’d been working as a telephone operator in L.A. to help save money for the journey. As she began to realize that her correspondent and the shabby figure who had just crossed her field of vision were one and the same, she frantically sorted through her options, considering a change of plan, but what could she do? She was alone in Venice and the Yugoslavian was becoming obnoxious, so she followed her fate to a summer on the road in Italy and Greece, marriage in New York, and 50 years later she’s living in Princeton with the Venetian apparition, who is struggling to begin a column about Bob Dylan without mentioning the fact that his life was changed by a meeting 50 years ago somewhere between the Piazza San Marco and American Express.

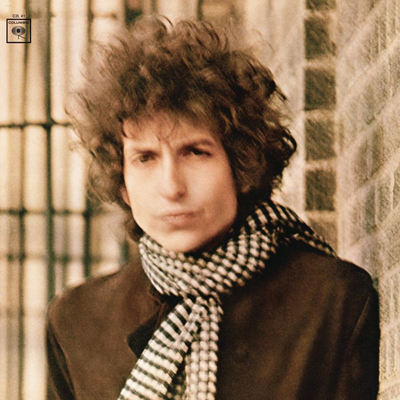

Backing Into Blonde on Blonde

The proof of a great songwriter is that somewhere in his repertoire is a lyric or a melody to fit any occasion. Some lines from Dylan’s “Simple Twist of Fate” (“They walked along by the old canal/A little confused, I remember well/And stepped into a strange hotel with a neon burnin’ bright) work for what happened that day in Venice.

It makes some kind of deranged Dylanesque sense to bring a meeting in Venice and a song from 1975’s Blood On the Tracks into a column about Blonde On Blonde, which came out 50 years ago, and Fallen Angels, which Columbia released last month to coincide with Bob Dylan’s 75th birthday.

I was too preoccupied that road-and-love-dazed summer to listen to a new album by Dylan or anything else with the exception of the Beatles’ Revolver, which became our first purchase as a couple. Blonde on Blonde had been celebrated, wondered over, studied, dissected, and debated for three years before I backed into it. At the time my reaction to the phenomenon from which so many people were deriving worlds of meaning was a zigzag pilgrim’s progress that involved performing spirited impersonations of Dylan’s outlandishly drawn-out phrasing: “I want you soooooo bad.” “Sad-eyed laydeee of the looooooow lands,” “ohhhh, maaamaaa, can this really beeee the end?” I was in graduate school at Rutgers at the time studying with Richard Poirier, author of The Performing Self, and essays like “Learning from the Beatles” and “The Politics of Self-Parody,” a concept that worked for stanzas like “See the primitive wallflower freeze/When the jelly-faced women all sneeze/Hear the one with the mustache say, ‘Jeeze/I can’t find my knees.’”

Shakespeare in the Alley

I finally bought Blonde on Blonde because not having it in my rapidly growing record collection would be like not having Moby Dick or Ulysses on my book shelves. To own it was to love it. In certain ways, my feeling for it symbolizes my liberation from the academic rat race of about-to-be-delivered PhDs. Much of my enduring fondness for “Stuck Inside Of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again” has to do with its real-life adaptability as a remedy for the slings and arrows, longeurs, and stalemates of existence, so if you’re bored with grad school or Princeton, just substitute it for “Mobile” and then add the place you’d rather be for “Memphis.” Still and all, the zany allusive energy of the song brings back the moment I abandoned the dissertation-littered base camp at Mt. Hamlet for Dylan’s Shakespeare “in the alley with his pointed shoes and his bells speaking to some French girl who says she knows me well.”

Another song that to this day continues to liberate, charm, and disarm is “I Want You” with the deliriously straight-ahead music driving the word-joy of “guilty undertakers,” “lonesome organ grinders,” “silver saxophones,” and “cracked bells and washed-out horns.” There’s no resisting the freeflow programming on Radio Dylan (WBOB) where “Visions of Johanna,” the song that rhymes geez and knees, illuminates a place and a period and a mood (like 1960s Chelsea Hotel New York) in one line, “In this room the heat pipes just cough/the country music station plays soft/but there’s nothing really nothing to turn off.”

All these years later, I find the Jeeze/knees mantra a curseworthy part of my everyday life (impossible to say “Jeeze” without the rest) while the same song’s “ghosts of electricity burn in the bones of her face” induces a graduate-school-recall cringe and a smile to think how so heavy a turn of phrase would go down with Little Richard (“Oh my lord!”) or Fats Waller (“One never knows, do one?”). Otherwise such loaded lines make good bait for the Dylanologists, the same way the Proteus sequence in Ulysses (“the ineluctable modality of the visible”) does for scholar critics of Joyce. When Dylan is having fun, as he so often does in Blonde On Blonde, it’s like Fats Waller winking or Leopold Bloom feeding a kidney to a cat or Molly saying “Yes!”

Getting Carried Away

While the notes on The Best of the Cutting Edge, 1965-1966 by Sean Wilentz and Al Kooper provide a key source of inside information about the Nashville sessions that produced Blonde On Blonde, Dylan himself offers some insight into how the songs evolved on the spot. “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” the elegaic side-long closing track Dylan once described as “old-time religious carnival music,” started out “as just a little thing,” he says in a 1968 Rolling Stone interview, “but I got carried away somewhere along the line. I just sat down at a table and started writing … at the session itself … and I couldn’t stop. After a period of time, I forgot what it was all about, and I started trying to get back to the beginning.”

Meanwhile, “the tired, strung-along musicians shot the breeze and played ping-pong while racking up their pay.” Finally, at 4 a.m., Dylan was ready. Even then, he kept “polishing the lyrics in front of the microphone. After he finished an abbreviated run-through, he counted off, and the musicians fell in.” Drummer Kenny Buttrey “recalled that they were prepared for a two- or three-minute song, and started out accordingly,” but after “about ten minutes of this thing we’re cracking up at each other, at what we were doing. I mean, we peaked five minutes ago. Where do we go from here?”

“Melancholy Mood”

The best way to hear Fallen Angels, another album of Tin Pan Alley standards from the same session as last year’s Shadows of Night, is with headphones, preferably late at night, with the lights down low and no one else in the room. Released as a single, “Melancholy Mood” sounds the theme of lostness and loneliness suggested by the CD booklet’s reproduction of vintage ads (“Lonesome? Let us help you find that certain someone”). It’s not a song so much as a do-I-wake-or-sleep afterthought, as if the singer had wandered out of a dream (“melancholy mood forever haunts me, steals upon me in the night”), but you can see why the composer of “Absolutely Sweet Marie” (“just like me, obviously,” “like you, fortunately”) would be responsive to “love is a whimsy, as flimsy as lace/And my arms embrace an empty space.”

The saving grace of Fallen Angels is that, far from being alone, Dylan is in the best possible company — “accompaniment” is too small a word for guitarists Charlie Sexton, Stu Kimball, Dean Parks, bassist Tony Garnier, drummer George Recile, and the soul of the session, Donnie Herron on steel guitar and viola. This is probably the most significant element Fallen Angels has in common with Blonde On Blonde, where the playing of Buttrey, Charlie McCoy, Joe South, Wayne Moss, Robbie Robertson, and company is no less stunningly supportive.

The beauty of it is that in 1966 and 2016, the same leader is able to bring with him such a perfect complement of musical talent, and through it all, even when his voice cracks and you hold your breath as he reaches for a note, Dylan is picking up and reimagining these fallen angels, including “All the Way,” a song Sinatra owned. Dylan turns it around when he sings “Who knows where the road will lead us, only a fool could say.” The road belongs to Dylan. In his memoir, Chronicles Volume One, he says of his maternal grandmother, “She was filled with nobility and goodness, told me once that happiness isn’t on the road to anything. Happiness is the road.”

In music and life nothing is that easy. Back we go to the meeting in Venice and some more lines from Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, “still on the road/Headin’ for another joint/We always did feel the same/We just saw it from a different point of view/Tangled up in blue.”