Henriques, Author of Book About Madoff, Details His Methods of Deceiving People

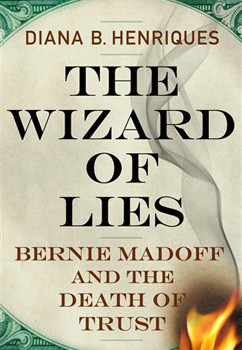

The crimes of Bernard Madoff have occupied journalist Diana Henriques since the details of his stunning, $65 billion Ponzi scheme began to unfold in December 2008. Ms. Henriques, a senior financial reporter for The New York Times and the only journalist to have interviewed Madoff in prison since his incarceration, has written a book about the scandal, The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust, published by Henry Holt and Company.

The crimes of Bernard Madoff have occupied journalist Diana Henriques since the details of his stunning, $65 billion Ponzi scheme began to unfold in December 2008. Ms. Henriques, a senior financial reporter for The New York Times and the only journalist to have interviewed Madoff in prison since his incarceration, has written a book about the scandal, The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust, published by Henry Holt and Company.

Ms. Henriques’s fascination with the now-legendary character continues. As guest speaker at the Princeton Regional Chamber of Commerce’s monthly luncheon at the Princeton Marriott on January 5, she expressed amazement at the way that Mr. Madoff, a quiet loner, was able to gain people’s trust and carry out decades of deception.

“We don’t know exactly when he stepped over the line and began to cheat,” she said, adding that her research leads her to believe it had definitely started by about 1987. “Regardless,” she added, “Madoff put his own distinctive stamp on what is an age-old crime: Robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Mr. Madoff conducted what is considered to be the largest financial fraud in U.S. history. In March 2009, he pleaded guilty to 11 federal felonies and admitted to turning his wealth management business into a massive Ponzi scheme that defrauded thousands of investors, from individuals to large, charitable foundations. Clients, located across the globe, ranged from friends and relatives of Mr. Madoff to foundations started by filmmaker Steven Spielberg and author Elie Wiesel.

Ms. Henriques, whose local connections include stints at The Lawrence Ledger and The Trenton Times, credits Mr. Madoff’s troubled upbringing in Queens, N.Y. to his criminal behavior. “His father’s serial business failures put the family in a precarious financial state,” she said, leading to his “nearly pathological inability to meet failure.” As early as 1962, when faced with the choice of admitting failure at one of his ventures, he lied.

“Even then, he found it easier to lie,” Ms. Henriques said. “When I first interviewed him in prison, he refused to even admit he had failed at his Ponzi scheme. He simply got tired of the constant tap dance he had to do to raise fresh cash, and he quit. He let it collapse.”

For several years before the 2008 scandal, Ms. Henriques knew Mr. Madoff as the head of a small firm that was often open past the market’s 4 p.m. closing time, making him a frequent source for late-breaking information. Never, in those days, would she have imagined him as a criminal mastermind, able to convince people to entrust him with their life savings.

“He was a quiet, soft-spoken loner who hated parties,” she said. “Unlike the classic Ponzi schemer, he treated you like you were the smartest person in the room. Instead of trying to impress you that he was a Wall Street wizard, he seemed impressed by you. It was a remarkable form of emotional jiu-jitsu. People were blinded by his quiet magnetism and laid-back confidence. He could win your trust, and that is the sine qua non of Ponzi schemers.”

While other Ponzi scheme masterminds exploited investors’ greed, Mr. Madoff exploited their fear. What people fear most, Ms. Henriques said, are the risks of an increasingly complex market that they don’t understand. “Consistency, safety, and security — that’s what he promised,” Ms. Henriques said. “Americans baffled by the market placed their trust in people like Madoff.”

By the time Ms. Henriques made her second visit to Mr. Madoff in prison, his son Mark, unable to withstand the constant implications that he and his brother were involved in the scheme, had committed suicide. “On the first visit, I could sense only self-deception and denial,” she said. “But on the second visit, I saw a shattered man, almost unrecognizable from the man I had met earlier. There is no doubt he feels remorse, but just how much, I don’t know.”

Ms. Henriques concluded her talk by speaking of lessons that can be learned from the Madoff scandal. “All of us need a crash course in the care and handling of the wizards in our lives,” she said, “before we encounter the next Bernie Madoff.” As an example, she mentioned former New Jersey governor Jon Corzine, who resigned last November from his position as chief executive officer of the MF Global securities firm amid an investigation into money that disappeared from client accounts as the company sank into bankruptcy. “Warnings were dismissed, because, well, Corzine was special,” she said. “He was a Wall Street wizard and seemed confident, until things blew up.”

Exceptions were made for Mr. Madoff despite many inconsistencies in his business practices because he, too, seemed like such a wizard. If more people had shared their doubts with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the outcome might have been different.

“We’ve got to figure out how to navigate in a world that runs on trust,” Ms. Henriques said. “The magic spell that keeps us safe from wizards is humility. I have a growing sense of certainty that we still haven’t learned our Madoff lesson. I just hope The Wizard of Lies can change that, one lesson at a time.”