Searching for a Phantom Melody on Ravel’s Birthday

All of life’s pleasure consists of getting a little closer to perfection, and expressing life’s mysterious thrill a little better.

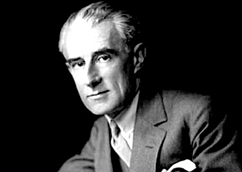

—Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

For the last four years of his life Maurice Ravel, who was born 137 years ago today, suffered from a form of aphasia so severe that he could only dream of expressing “life’s mysterious thrill.” After witnessing a performance of his great “symphonie choréographique,” Daphnis et Chloe, he’s said to have lamented, through tears, “I still have so much music in my head, I have said nothing. I have so much more to say.”

It’s painful to imagine what Ravel went through, exiled from his genius, his will in limbo, apparently the delayed result of a blow to the head suffered in a taxi accident in 1932. That he would be dealt this ultimately mortal injury in a car makes for a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction coincidence, given his fascination with mechanical devices, a quality inherited from his father, whose inventions included an internal-combustion engine and an automatic loop-the-loop circus machine known as “the Whirlwind of Death” that was popular at the Barnum & Bailey Circus — until it resulted in a fatal accident.

A Debonair Wizard

Ravel was intensely, severely handsome, 5’4, slightly built, and sensitive about his small stature. In his prime, he cultivated an enlightened dandyism inspired by Baudelaire’s ideal, which was to combine simplicity and elegance while carrying out “a dignified quest for beauty.” Léon–Paul Fargue described him at the time as “a sort of debonair wizard … telling me endless stories — he could tell an anecdote as well as he could compose a waltz or an adagio.” He was a heavy smoker, a serious gardener, a bird-watcher (he excelled at bird calls), with a fondness for spicy, exotic dishes, cocktails, fine wines, Spain, Morocco, books (he had a large library), and Siamese cats. He never married, though he is said to have proposed to and been refused by violinist Hélène Jourdan-Mourhange (apparently he returned the disfavor when the situation was reversed). He did, however, enjoy playing with the children of his friends and would tell them fairy tales. One such child said that when she heard the news of his death it was like losing her own father for a second time.

Ravel’s ideas on the nature and meaning of art were primarily based on his reading of Baudelaire and Edgar Allan Poe. During his highly successful concert tour of the U.S. in 1928 he made a pilgrimage to Poe’s home in the Bronx, visited 25 cities from New York to California, enthused about skyscrapers and jazz (“I am seeing magnificent cities and enchanting regions,” he wrote to Jourdan-Morhange). He began a lecture at Rice Institute in Houston with reference to the “singular importance” for him of “the aesthetic of Edgar Allan Poe, your great countryman.” In the same lecture, he talked about the blues “one of your greatest musical assets,” and mentioned the blues element in the second movement of his sonata for violin and piano.

In fact, American music took more from Ravel than the other way around. Listen to the orchestral pieces, notably Daphnis and Chloe, and you know that Hollywood composers like Miklos Rosa and Bernard Herrmann have been there, not to mention bandleader Stan Kenton, whose signature theme, “Artistry in Rhythm,” borrows from the ballet’s opening sequence, “Invocation to the Nymphs.” You can hear echoes of Ravel in the mood-drenched music of film noir and 1940s classics like Hitchcock’s Spellbound, and numerous rock and heavy metal barn-burners have fed on the hypnotic rhythms of his Bolero, which spawned the 1934 film of the same name wherein Carole Lombard and George Raft (and their long-shot doubles) perform to Ravel’s music what may be the most erotic dance sequence in all of pre-code Hollywood.

Pilgrim’s Progress

Jazz pianist Bill Evans openly declared his debt to Ravel, and turned Miles Davis on to A.B. Michelangeli’s recording of the piano concerto in G, which eventually “became something of an obsession with Davis,” to the point where he “proselytized about it for years,” according to John Szwed’s So What: A Life of Miles Davis.

“When he plays something,” Davis said of Michelangeli’s interpretation,” it sounds like he’ll never play it again.” The words “never play it again” have a poignant resonance, for this work was first performed in 1932, the year Ravel suffered the blow that extinguished his career. The endgame quality is best heard in the original recording by Ravel’s friend, Marguerite Long, the French pianist to whom the work was dedicated. In the world of beauty created by the Adagio assai, the pianist seems to be tracing a pilgrim’s progress through dark woods shadowed by a vague furtive menace, the right hand’s walk through the shadows at times nearly thwarted, halting, almost wavering, before thoughtfully, steadfastly moving on, then simply ascending, beautifully buoyed by strings and woodwinds, to a blissful extinction, with the orchestra, reportedly conducted by Ravel himself, swooning into silence at the gates of the heavenly city.

Linking Melodies

It’s said that Ravel composed the Bolero by picking out the melody on the piano with one finger and commenting approvingly on its “insistent quality,” which he decided to try repeating a number of times “without any development, gradually increasing the orchestra as best I can.”

The seemingly random simplicity of that moment at the keyboard, the composer, in effect, taking baby steps on the way to a work of epic grandeur, suggests an analogy for the series of conundrums and coincidences that led to the writing of this anything but epic column. The wonder of music is that it can catch and disarm you in the most unlikely places, for instance when you’re being ministered to by a dentist who suddenly expresses his fondness for an album that contains a Billy Strayhorn composition you feel especially close to but whose title you can’t remember. So while the dentist is busy threading your gums with stitches, you’re racking your brain for the name of one of the moodiest and most classically nuanced numbers Strayhorn ever wrote. At this point, somewhere in the internet of your mind, a link is forming, with Strayhorn the primary subject, the bait that helps you reel in Ravel, whose mere name brings you closer to the music itself; you can almost hear Ben Webster’s tenor brewing and serving it up with a melodic sibling from Ravel that means more to you than it should because it briefly illuminates a distant scene involving a grand piano, and presto, that ghostly fragment of Ravel conjures up “Chelsea Bridge,” the title you’ve been trawling the web for. Returning home, you go straight to the most credible authority, Gary Giddins’s Visions of Jazz, and find that when composing “Chelsea Bridge,” Strayhorn “turned for instruction” to “Maurice Ravel.” Case closed? Not a chance. What about that “ghostly fragment of Ravel?”

A week later, looking ahead to the March 7 issue of Town Topics, I find that Maurice Ravel was born on March 7, 1875. No less important for the solving of the second mystery is the fact that he died on December 28, 1937, three days after my parents were married. Now the “distant scene” I saw in the dentist’s office comes into focus on the shiny black grand piano that was the great game-changer of my parents’ marriage, for whenever the tension reached the danger level, my cool, remote father would sit down at the keyboard and flood the living room with the warmth and power of his playing, pulling out the stops, unloading every weapon in his arsenal as he melted my sulking, formidably emotional mother. And what was one of my father’s primary weapons? A piece by Ravel, of course. That phantom fragment. But what was it?

The Thrill Is Not Gone

The first jazz record I played incessantly enough to provoke disparaging remarks from my parents was Chet Baker’s initial solo EP on Pacific Jazz. I was 14 and so enamoured of the music that I asked my father to give me piano lessons, a prospect that horrified him. He did, however, teach me how to pick out “Isn’t It Romantic,” my favorite song on the album.

Knowing what I know now, I wonder what his reaction would have been had I asked him to teach me my next favorite number, “The Lamp is Low”? Surely he’d have recognized one of his primary weapons in the melody, which was borrowed from Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Princess, otherwise known as “Pavane pour une infante défunte” and dedicated to the Princesse de Polignac, a.k.a. Winnaretta Singer, heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune.

That’s it. Mystery solved. After listening to numerous renditions of Ravel’s Pavane, I have no doubt that it’s the melody I was looking for, the one my father played. But there’s still another link to open, the one leading to “life’s mysterious thrill” in its purest form, which is when beauty appears unexpectedly in an unlikely place and in the guise of a dubious medium.

Working the internal internet again, I pull up my first summer in Europe. The student tour that had begun two months before in June is almost over and I’m sharing a moment with a fellow I’ve only really begun to know — a shambling, wisecracking Phil Silvers type, a sort of playful Teddy Bear who has let on that he’s a musician. We’re in an empty recreation room on a rainy day at a student hostel in the Lake District town of Patterdale and he’s at the piano playing an elaborate, astonishingly accomplished composition of his own based on a viscerally familiar melody. Speaking musically, the tour has been two months of drunken dissonance, which gives this moment with the rain pattering at the misty windows in Patterdale a special provenance, for it turns out that this amiable Teddy Bear isn’t just a gifted musician in a realm well beyond my father’s, he’s a genius who will go on to a recording and recital career in Europe accompanying famous lieder singers, and the theme he’s built his version of a “mysterious thrill” around is the phantom melody from Ravel’s Pavane that has been haunting me ever since that day with the dentist.

———

Of the quantities of Ravel material online, I’ve consulted and sometimes quoted from Roger Nichols’s biography, Ravel (Yale University Press 2010), Arbie Orenstein’s A Ravel Reader (Dover 2003), and Deborah Mawer’s Cambridge Companion to Ravel (Cambridge University Press 2000). The version of “Chelsea Bridge” referred to is from the album, Ben Webster Meets Gerry Mulligan. Although the music I’ve referred to is available online, notably Marguerite Long’s historic performance of that chillingly beautiful Adagio, the Princeton Public Library provided the CDs I’ve been listening to, the stand-out being Claudio Abbado and the London Symphony Orchestra’s Daphnis and Chloe, which filled my humble CRV with with its orchestral power and choral glory from here to Lambertville and back.