You Can Always Get What You Didn’t Know You Wanted at the Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Sale

Based on my experience last week, the best things to be found at used book sales like Bryn Mawr-Wellesley are the ones that you didn’t know you wanted and, in this case, that you didn’t know existed.

Based on my experience last week, the best things to be found at used book sales like Bryn Mawr-Wellesley are the ones that you didn’t know you wanted and, in this case, that you didn’t know existed.

What I was looking for when I walked into the sturm und drang of the Thursday preview was something with a story or a cover quaint and curious enough to write about and reproduce on this page. What I found was a new paperback edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and a like-new copy of Debussy On Music, both of which will be of use for future columns on Sinclair and Debussy, whose 150th birthday falls on August 22.

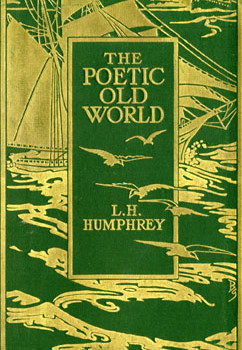

The closest thing to a “want” that I found at the preview was a volume from 1908 with a handsomely embellished Art Nouveau style cover titled The Poetic Old World: A Little Book for Tourists, which I abandoned on the cookbook table when the surprise announcement was made that Collectors Corner, the domain of rarities, was “open to everyone.” I naively assumed that my find (edited by one Lucy H. Humphrey) was safe tucked between Beard on Pasta and a trashed copy of The Joy of Cooking. When I got to Collectors Corner, a dealer was walking out with a big box in his arms and a big smile on his face. Five minutes later, after finding nothing in the CC, I went back to the cook book table and The Poetic Old World was gone. After rummaging around in the vicinity, I gave up. I felt only mild regret, not having had time to fully appreciate the gem I had so thoughtlessly thrown to the winds.

I left the vaunted preview with nothing visually enticing enough to show off here, except perhaps the third edition of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, with its tan buckram cover (the big red “T” set in a little gilt window). It always feels good to find anything early by Stephen Crane and it would have given me an excuse to write about a man who, if American literature were baseball, would be the catcher on my personal all-star team. A best-seller in its day, the Red Badge isn’t particularly rare in later editions, even ones from 1896, although most book people who can see beyond their scanners would have shelled out more than the $2 I paid for it.

“Tarry at the Taft”

What a difference a day makes. On Thursday afternoon, the first day of the regular free-admission sale, I immediately found six books I’d have gladly snatched up the day before, if they’d been there. One of the realities of the Bryn Mawr event is that dealers and book lovers gorging themselves on the first day often leave a few crumbs behind, most likely because the condition is just a bit off or the price a bit too high. With my small stack of dealer rejects in one arm, I went downstairs to the main room and found Lucy H. Humphrey’s The Poetic Old World among the neglected masses on the poetry table.

I was still smiling when I walked over to the literary classics table and found this year’s treasure, my heart’s desire, which had been picked up, stashed, pondered over, and tossed back into the Bryn Mawr book stream for some dutiful volunteer to fish out and return to its rightful place early that morning, and now there it was, waiting for me. Reader, how often do you see a small professionally bound hard cover copy of A Tragedy By the Sea and Other Stories by Honoré de Balzac with a decorated Deco cover featuring a raised image of the Taft Hotel and the words “Compliments of the HOTEL TAFT New York” imprinted in the lower right-hand corner? Open it and on the inside cover you see a simulated Ex Libris book plate with a space for the name of the guest (“This Book Belongs To”) under another image of the hotel (“Adjoining the Roxy Theatre”). Think about it: 70-plus years ago, a big New York hotel a stone’s throw from Times Square published Balzac’s stories under its own imprint (“Tarry at the Taft”) while alerting its guests to the fact that it adjoined, was connected to, in touch with (avoisiner in French) one of the city’s foremost movie palaces, which could be entered directly from the hotel according to an online website about the Taft.

So why this rush of mindless joy? Only because the book fates who gave me this gift obviously knew how I felt about New York and big New York hotels, thirties movies and the Roxy, not to mention Balzac. What really got me was the idea that the management of a major Manhattan hostelry during the Great Depression would go to such quixotically thoughtful lengths for their guests. Would you believe that Tarry at the Taft also published The Picture of Dorian Gray? And Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue? And at least half a dozen others, including Alice in Wonderland? Wilde, Poe, Balzac, and Alice! I mean, what sort of guests, aside from me, did they have in mind?

Imagine you’re coming to the city for the first time, a young writer in the 1930s, thinking to splurge by spending your first night at a great Times Square hotel, and you walk into your room and find this little orange book waiting for you on the bedside table. And outside maybe it’s windy and raining and the radiator’s knocking like a demented spirit, so you crawl under the covers, open the book, and lose yourself in Balzac’s Paris, which is to say, in Balzac’s mind, heart, and soul, and he’s writing about the great surgeon Despleins (in Balzac, as Swinburne observed, everyone is a genius), “this perpetual observer of human chemistry” who possesses “the knowledge of the elements in fusion, of the causes of life, of life before life, of what from its preparations it will be before it is” — okay, so it’s a clumsy translation, not to worry, life goes on.

The first paragraph is three pages long, no break, and every now and then you can hear the soundtrack from the movie at the Roxy (sounds like Henry Fonda taming the lynch mob in Young Mr. Lincoln), it’s not a smooth ride, you soar and sink, the unnamed translator staggering about as if in drunken awe as Balzac dissects the surgeon’s atheism, “recognizing in man a cerebral center, a nervous center, and an aerosanguineous center … convinced during the last two or three days of his life that the sense of hearing was not absolutely necessary for hearing, nor the sense of sight absolutely necessary for seeing, and that the solar plexus could replace them beyond suspicion of any change.”

Finally coming up for air, brought to attention by the horns honking down below on the passage au Commerce (except you’re no longer in Paris, it’s a line of Yellow Cabs on 50th Street), you begin to realize where you are. Only then does it hit you: that three-page-long Balzacian cadenza came with the room, compliments of a hotel that not only serves its guests but contains its own publishing venture, or so I like to think. So where did they get that weird translation? Nathaniel West worked in more than one Manhattan hotel during the Depression. Maybe he sent some down-and-out editor pal who’d lost his job to sell the idea of an in-house reprint line to the manager of the Taft, who then hired a needy writer (a Woody Allen type) to translate Balzac’s stories rather than pay some publisher for the right to use the existing translations of Clara Bell or Ellen Marriage. I can just see it: the hotel manager banging on Woody’s door — ”Get a move on, kid! We go to press in a month!”

Lucy and Henry

The dozen or so books I found at the big sale reflect two different states of mind. The first bunch came from the chaos of the preview; the second, better group from the relative calm of the following afternoon. The Poetic Old World bridges both days, since I found it, lost it, and found it again. I couldn’t learn much about Lucy Humphrey online beyond the fact that this was the sort of pocket-(or purse-) sized volume of “famous poems associated with historic and classic localities” that she herself had “longed for” when traveling in Europe. She compiled a sequel, The Poetic New World, that appeared in 1910. Otherwise she seems to have been known primarily for her translations, an art I became all too aware of while reading the Taft version of Balzac.

Who better to bring down the curtain on translations, finding and losing, and the old world, than Henry James? The 1889 edition of Guy de Maupassant tales called The Odd Number, a book I found on the first day, has an introduction by the Master, who begins to the effect that it is “embarrassing to speak of the writers of one country to the readers of another,” for “One should never go out of one’s way to differ, and translation, interpretation, the business of adjusting to another medium, are a going out of one’s way. Silence is the best disapproval, and to take people up, with an earnest grip, only to put them down, is to add to the vain gesticulation of the human scene.”

I bought 12 books altogether, two were $3, the rest were $2. Two of the $2 books have covers I’d show off here if we had room: from 1902, The Dragon of Wantley by Owen Wister (the third edition), nicely illustrated by John Stewardsom, and from 1889, The Bon Gautier Ballads, with illustrations by Doyle, Leech, and Crowquill. I was also glad to find the 1950 edition of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which I hope to read in connection with the Dickens bicentennial.