Two Days in Washington D.C. — Stirred by Lincoln, Surprised by Whitman

Whitman’s Washington consisted of an unfinished Capital dome with blocks of marble and granite strewn about its grounds. The Washington monument was not yet half of its present height of 555 feet. The Treasury, Post-office, and Interior Department buildings were unfinished as well. There were few sidewalks and only one theatre.

Whitman’s Washington consisted of an unfinished Capital dome with blocks of marble and granite strewn about its grounds. The Washington monument was not yet half of its present height of 555 feet. The Treasury, Post-office, and Interior Department buildings were unfinished as well. There were few sidewalks and only one theatre.

—from Washington During War Time

Among a multitude of other things, bad and good, Washington D.C. is a city of statements on the Grand Scale. Right now one of the dominant statements is Construction, with Jobs as a positive subtext. The cranes are everywhere. Waiting in line for a cab at Union Station, you’re surrounded by a construction zone, with the dome of the capitol in the near distance looking a bit embattled. The cab must have skirted half a dozen such sites before it reached our destination, the Tabard Inn on N Street, one of the oldest continuously operating hotels in Washington. It’s also a survivor. According to the brochure at the front desk, efforts to demolish the property in the early 1970s “were halted when its neighbors rose up in protest.” If you happen to enter the lounge and restaurant during the dinner hour, as we did, you feel that you’ve walked into the busiest, most convivial gathering place in the city. There may be some other tourists here and there, but it soon becomes clear that the brochure is not stretching the truth when it claims that the spot “is a favorite haunt for journalists, publishers, and those involved in the arts and congressional intrigue.”

If “congressional intrigue” sounds like a line from a political thriller, no wonder, for it turns out that the Tabard Inn Hotel is a setting in numerous novels, including John Grisham’s Pelican Brief; Jerry Doolittle’s stories about Tom Bethany, “a Boston self-styled detective and wrestling buff who frequently visits his mistress in D.C.” Then there’s Les Whitten’s character “Frederick Tabard,” the senior partner of a prestigious law firm whose family founded the Tabard. It’s said that there was also a failed screenplay about a president “who hides in the Tabard’s secret Chrome Room to foil his pursuers.”

On the Mall

Construction is the story even on the National Mall, where visitors to the war memorials — World War II, Korea, and Vietnam — will find themselves navigating around the resurfacing of the walks and installation of sidewalks adjacent to the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool. Under construction in the other direction is the Museum of African American History and Culture. Other projects include memorials to President Eisenhower and American Veterans Disabled for Life, which the optimists among us can assume is so titled to include suicidal victims of post-traumatic stress disorder like the one mentioned in Nicholas Kristof’s column in this Sunday’s Times.

Numbers

Last Thursday we joined the crowd streaming toward the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. It seemed that all the kids from all the malls in America had been turned loose on the National Mall with the same objective: Maya Lin’s haunted and haunting black wall bearing the 58,000-plus names of the dead. The kids sustained a sort of easygoing decorum when they encountered the somber, stirring reality of the names. Not that they were quiet or even consciously respectful; it was as if the sheer power of the place created a hush in which they were submerged. I had no names to look for, but Richard Stuart Patterson caught my eye, my middle name being Patterson, which was my mother’s maiden name and the name on my uncle’s dog tag (Robert E. Lee Patterson, Jr.), which I keep close at hand; he was a bombardier, killed in a freak accident in February 1942. There are lots of Pattersons on the wall. Richard Patterson was born in Toledo, Ohio, spring of 1950, joined army September 1970, killed in action July 1971, one of the 58,000-plus.

Like the scale of the Mall, the numbers are extreme. Rounded off, World War I: 52,000, World War II: 415,000. Korean War: 34,000.

The staggering numbers of Civil War dead have recently been revised upward from 618,222 (360,222 from the North, 258,000 from the South) to 750,000, according to an April 2 story in the New York Times. Based on “newly digitized census data from the 19th century,” the death toll increased by more than 20 percent. You’d need another Mall, maybe ten Malls, to even begin to acknowledge the numerical no-man’s-land of the War Between the States. Against that unfathomable carnage, the National Mall exalts one leader above all others.

Follow the path from the Vietnam wall to the Lincoln Memorial and it’s like entering American history’s sacred ground. You feel you’re a pilgrim approaching some goal or concept beyond your power to comprehend. You seem to be looking at the summit of scale, above and beyond any horizon. One minute you’re admiring the way the magnitude of the monument overwhelms the tiny figures climbing the steps. Then you’re one of them, part of the scene, as you move slowly to the top, and there he is.

My favorite statue in the world is probably Rodin’s Balzac, not the one in the Museum of Modern Art’s sculpture garden, nor the one in the Rodin Museum, but the one occupying a polluted square in Montparnasse. But this white marble rendering of one infinitely human individual seated in a chair, less like a monarch on a throne than a tired father with a world of grief on his shoulders, warms me, chills me, fills me with love and hope, foolish though such thoughts may seem in view of what’s going on and will always be going on in the world, not to mention in this forever conflicted, problematic, scene-shifting, wheeler dealer dream of a city. Everywhere, on all sides, people are lifting an array of photographic devices, held high toward the massive presence, with the fond hope of taking home a portion of Lincoln.

Whitman’s Escalator

Washington’s grandeur is all the more impressive when you aren’t expecting it. In the DuPont Circle metro station the dizzyingly steep straight-up escalator tempts photographers to stand at the bottom taking aim to catch the uncanny effect of people gliding into view at the pinnacle of the mechanism, or else ascending like figures in some parable of heavenly ascension.

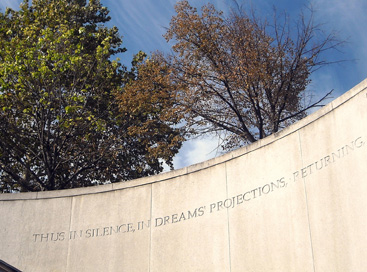

When the DuPont Circle escalator finally reaches the top and deposits you on firm ground, you may notice words engraved in capital letters along a sort of rotunda, THUS IN SILENCE IN DREAMS’ PROJECTIONS …. What’s that all about? Not exactly your run of the mill ceremonial platitude. Think how those six unlikely words might strike someone with an easily inflamed imagination who is perhaps already slightly drunk from the ascent. Imagine Camus or Coleridge or Emerson or DeQuincey, or any of their faithful readers, or any soul with a predilection for the unknown, rising from the subterranean depths to find that unfinished sentence waiting to be followed around to its completion on the other end of the rotunda. RETURNING, RESUMING, I THREAD MY WAY THROUGH THE… Unless you’re a student of the poet whose words you are now following, walking beside, as near as you can get to them without tumbling into the depths of the escalator pit, you will be wondering what dreams? returning from what? resuming what? threading your way where? Only when you arrive at the word HOSPITALS does the identity of the author become clear, and when it does, it makes perfect sense because of the thousands and thousands whose names were on that long black Vietnam wall, THE HURT AND WOUNDED I PACIFY WITH SOOTHING HAND which Walt Whitman did in one or the other of Washington’s 56 makeshift hospitals when he was living in Washington between 1862 and 1865. I SIT BY THE RESTLESS ALL THE DARK NIGHT SOME ARE SO YOUNG If you look at the online information about each of the soldiers named on Maya Lin’s wall, you’ll find that the majority were between 18 and 20. SOME SUFFER SO MUCH. It’s hard to make out the words on the far side: you practically have to tiptoe along the edge of the abyss (no one can put as much feeling into a simple “so” as Whitman, who nursed the wounded, wrote to their families, held their hands). I RECALL THE EXPERIENCE, SWEET AND SAD.

The last two lines of the stanza, from “The Wound Dresser,” have been left off, perhaps not because Walt crossed the line with references to soldier’s “loving arms” about his neck and “soldier’s kiss on these bearded lips” but because there simply was no room.

Reading Walt Whitman’s account of his time in Washington in Specimen Days and in his journals and letters, you begin to think that if Lincoln had not existed, Whitman would have invented him. Admiring the president on horseback, “dress’d in plain black, somewhat rusty and dusty, wears a black stiff hat,” Whitman approvingly observes that he “looks about as ordinary in attire, &c., as the commonest man.” In a letter written shortly after Lincoln took office, the Good Grey Poet sees a face “like a Hoosier Michelangelo, so awful ugly it becomes beautiful.”

———

Washington During War Time is an anthology published in 1902 by the Tribune Company.