Woody Guthrie’s Book-Writing, Subway-Riding, Swamp-Crossing, 100th-Birthday Blues

“I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world.”

“I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world.”

—Woody Guthrie (1912-1967)

Hey, hey Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

‘Bout a funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ along.

Seems sick an’ it’s hungry, it’s tired an’ it’s torn,

It looks like it’s a-dyin’ an’ it’s hardly been born.

—Bob Dylan, “Song to Woody”

When the folks next door gave us the new Neil Young record, Americana, I wasted no time sliding it in the CD player on Moby, my four-wheeled stereo CRV. As happened last month with the Beach Boys’ new one, That’s Why God Made the Radio, I let the thing keep playing, five times at last count, as I drove around town. To borrow an old term from MTV’s heavy metal youth, it was a high octane headbanger’s ball as Neil and Crazyhorse beat the joyful daylights out of old singalong favorites, including “Clementine,” “Oh Susanna,” “Travel On,” and Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.”

Although I was unaware until a few days ago that Woody Guthrie’s centenary was upon us, what better prelude to the event than all this pounding, full-throated vintage Americana? It was Neil Young, after all, who inducted Guthrie into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988. In his remarks, Young said that when he was in high school he thought “maybe I’d like to be one of those rockers that could bend the strings and get down on my knees, and kind of make everybody go crazy. Then I wanted to be that other guy, too, that had a little acoustic guitar, and sing a few songs — sing about things that I really felt inside myself, and things I saw going on around me.” He doesn’t come right out and say so (“I don’t know which one of those guys I tried to be”), but of course Neil Young is not only one of the most go-crazy-everybody guitar madmen in the universe, he is a passionately committed, devoted-to-the-message singer songwriter with one of the great rock and roll voices, full of hope and heartbreak, and as searing as a siren in the night.

“It all seems to go back and start with Woody Guthrie,” Neil said near the end of the Hall of Fame remarks. “His songs are gonna last forever, and some of the songs of his descendents are gonna last forever.”

While the first such descendents to come to mind are Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, there’s also Johnny Depp, who grew up in Kentucky “on bluegrass and country music,” has listened to Guthrie all his life, and is editing with Douglas Brinkley Guthrie’s only novel, House of Earth, which will make its publishing debut next year. In the back page essay in last Sunday’s New York Times Book Review, Depp and Brinkley locate “the roots” of the novel in Guthrie’s Dust Bowl experiences, his reading of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and the writing of “This Land Is Your Land,” which he “conceived of” while hitchhiking to New York and wrote in late February of 1940, “holed up in a low-rent Times Square hotel.”

Not surprisingly, the version in Americana sung by Neil Young restores the more contentious verses, such as:

By the relief office I saw my people.

As they stood hungry,

I stood there wondering if God blessed America for me.

And:

There was a high wall there

That tried to stop me

A sign was painted that said ‘Private Property’

But on the other side it didn’t say nothin’

That side was made for you and me.

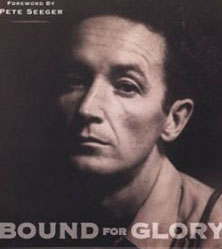

With a few adjustments, those words still have some significance in the time of the 99 percent. Centenary Princeton coincidences abound here, given what Woody reveals in his wordslinging memoir, Bound for Glory (1943): “Born 1912. That was the year … my papa and mama got all worked up about good and bad politics and named me Woodrow Wilson.” Only ten days before Woody came into the world, the other Woodrow, Princeton graduate, professor, and president, then governor of New Jersey, had been nominated for president on the 46th ballot at one of the wildest Democratic conventions ever, which took place 12 days before Woody came into the world on July 14.

Woody in the Apple

At the end of Hal Ashby’s visually stunning film version of Bound for Glory (1976), Woody (played wisely and well by the late David Carradine) is headed for New York City. The Times Square hotel where “This Land Is Your Land” was written was the Hanover House, located on West 43rd and Sixth Avenue, “a long block from the New York Public Library,” according to Ed Cray’s 2004 biography, Ramblin’ Man. Guthrie’s American anthem, orginally titled “God Blessed America for Me,” was written as a corrective to Irving Berlin’s forthrightly patriotic, “God Bless America.” The tune came from the Carter Family’s “Little Darlin’, Pal of Mine,” which, typically, derived from a Baptist hymn, “Oh My Lovin’ Brother.”

Some of the most colorful prose in Bound for Glory is inspired by his response to the big city. Sixty-five stories up (“Quite a little elevator ride down to where the world was being run”), he riffs on the Rainbow Room “in the building called Rockefeller’s Center, where the shrimps are boiled in Standard Oil” (a line ready made for the song in which it became “they tossed their salad in Standard Oil”): “I was floating in high finances, sixty-five stories above the ground, leaning my elbow on a stiff-looking tablecloth as white as a runaway ghost, and tapping my finger on the side of a big fishbowl. The bowl was full of clear water with a bright red rose as wide as your hand sunk down in the water, which made the rose look bigger and redder and the leaves greener than they actually was.”

Subway

There’s a photo from 1943 of Woody playing and singing on the subway that belongs with the iconic New York images of an overcoated James Dean walking, hands in pockets, in the middle of a rainy night Times Square and a decade later, a tan-jacketed Bob Dylan walking down West 4th Street in the Village with Suze Rotolo on his arm. My first thought was of Walker Evans’s clandestinely snapped pictures of subway riders between 1938 and 1941, most of which show seated passengers, with the exception of a blind accordion player standing and playing in the middle of a crowded car. Evans’s slightly unfocused image pales next to Eric Schaal’s photograph of Woody, who is also standing in the middle of the car bundled in what appears to be a black pea coat with a dark cap pushed back on his head, his eyes closed or perhaps downcast in a singing trance that gives his face a naked, exposed, almost beatific quality. If you’re accustomed to the more common images of Woody as the craggy, raw-boned Dust Bowl wayfarer, you might not even recognize him. He looks exotic enough to pass for, say, Jean Louis Barrault’s street-singer brother, having climbed aboard the D train fresh from the Boulevard du Crime in Marcel Carné’s film, Les Enfants du Paradis, his face lit with the otherworldly radiance of the mime Baptiste’s in one of his dumbshow reveries.

Twenty-one of the pictures Schaal took as he followed Woody Guthrie around New York can be seen (and should not be missed) in Life.com’s 100th birthday tribute, “Woody Guthrie: Photos of an American Treasure” at http://life.time.com/culture/woody-guthrie-in-nyc-1943. Guthrie’s politically suspect wartime reputation presumably explains why these flattering, sympathetic photos of Woody as a folk hero never showed up in the pages of Henry Luce’s Life magazine.

Dylan Crosses the Swamp

In his memoir, Chronicles Volume One, Bob Dylan describes a visit to Guthrie at Greystone Hospital in Morristown New Jersey during which Woody mentioned some boxes of songs and poems stored in the basement of his house on Mermaid Boulevard in Coney Island. Having been told he’s “welcome to them” if he wanted them (Woody’s wife “would unpack them for me”), Dylan rides the subway all the way from the West 4th Street station to the last stop and finds himself walking across a swamp (“I sunk in the water, knee level, but kept going anyway — I could see the lights as I moved forward, didn’t really see any other way to go”). When he comes out on the other end, his pants are drenched, “frozen solid,” and his feet are “almost numb.” Guthrie’s wife isn’t there, just a nervous babysitter who wouldn’t let him in until Woody’s son Arlo tells her it’s okay. Nobody knows or can do anything about the box in the basement. Staying just long enough to “warm up,” Dylan turns around and trudges back across the swamp to the subway in his waterlogged boots. Like so much in Chronicles, this anecdote is a song in itself, waiting to be written, even though it would have been better yet had Dylan forged the swamp with his arms weighed down with boxes of Guthrie’s songs and poems.

As Dylan goes on to explain, Woody’s lyrics “fell into the hands” of Billy Bragg and Wilco, who “put melodies to them” and brought them “to full life” in the first of a series 40 years later. Mermaid Avenue: The Complete Sessions was released this year on Record Store Day, April 21, in a 3-disc box set to commemorate Woody Guthrie’s 100th birthday. Also in honor of the centenary, the Smithsonian has released Woody at 100, a 3-CD boxed set including 57 tracks and dozens of Guthrie’s drawings, paintings and handwritten lyrics.