Debussy, Born 150 Years Ago Today: “One Can Travel Where One Wishes and Leave By Any Door”

Music is a dream from which the veils have been drawn! It’s not even the expression of a feeling — it is the feeling itself. —Claude Debussy (1862-1918), from a letter

Music is a dream from which the veils have been drawn! It’s not even the expression of a feeling — it is the feeling itself. —Claude Debussy (1862-1918), from a letter

On a spring morning in 1884 a classroom window at the Paris Conservatoire is open to the racket of horse-drawn omnibuses on the cobblestones of the rue du Faubourg–Poissonnière. At the piano sits a “dishevelled” 21-year-old student, “his shock of tousled hair constantly shaking,” as he produces “chromatic groanings in imitation of the buses … all the notes of the diatonic scale heard at once in fantastic arrangements; shimmering sequences of arpeggios contrasted with trills played by both hands on three notes simultaneously.” The performance continues until a supervisor hearing the “strange noises ringing through the corridors” puts a stop to it, branding the pianist “a dangerous ‘fanatic’ “ and ordering the “spellbound” students “to be off.”

In his rich two-volume biography, Debussy: His Life and Mind (Macmillan 1962), Edward Lockspeiser presents this “picturesque episode,” recalled after Debussy’s death by a fellow student, as an example of the way “all sounds must strike at some poetry” in “the mind of a musician.”

The same classroom observer, Maurice Emmanuel, was taking notes on a later occasion, during a conversation between the then-28-year-old Debussy and his former teacher, Ernest Guiraud. Debussy having just played a series of intervals on the piano, Guiraud asks “What’s that?” Debussy replies, “Incomplete chords, floating …. One can travel where one wishes and leave by any door. Greater nuances.” To which Guiraud responds, “I am not saying what you do isn’t beautiful, but it’s theoretically absurd.” Says Debussy, “There is no theory. You have merely to listen. Pleasure is the law.”

“Mystery in Art”

Drawn to that concept of composition, of music as a fluid infinitely malleable element and pleasure as the law, Debussy would surely have appreciated knowing that in a future time his work would be moving through the world at large giving comfort and joy and evoking wonderment and awe in intimate situations and unlikely environments far from the formal boundaries of the salon or concert hall, transmitted in forms undreamed of in his day, with plugged-in listeners walking, driving a car, flying across oceans and continents at 30,000 feet, or in the solitude of home, recumbent with headset in the dead of night, able to leave and return “by any door” with the push of a button, living, breathing, thinking music.

Debussy might be appalled at the idea of someone doing menial chores (the dinner dishes, in my case) while master pianist Aldo Ciccolini, born August 15, 1925, seven years after the composer’s death, is playing L’Isle Joyeuse, a work for piano composed in 1904. But this is Debussy, who could hear music in the sound of wheels on pavement while creating chromatic equivalents. Myself, I think he’d be tolerant of such mundane miracles, if not amazed and delighted, based on what evidence we have — the scene in the classroom, the conversation with Guiraud, and other statements, notably the one inspired by the paintings of JMW Turner, “the greatest creator of mystery in art.” Revert from the translation to Debussy’s actual words (“le plus grand créateur de mystère qui soit en art”) and it’s easier to see that he’s describing himself, his dream, his mission, which is how it often is when artists, whatever the medium, use works they admire to express the terms of their own aesthetic.

Admitted, “mystery” is a notoriously open term, but serviceable enough to express strange and wonderful transmissions such as the one from the young English poet who died in 1821, his name “writ in water,” the verse message reaching Debussy two months before his own death, sent by a friend who suggested the line, “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter,” from John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” was “implicitly dedicated” to a composer who once defined music as “the silence between the notes.”

Joy in Jersey

I mentioned L’Isle Joyeuse, which refers to Jersey, in the Channel Islands, where in July 1904 Debussy “eloped” with Emma Bardac (both being already married at the time), who would become his second wife and the mother of his only child. The composition for piano finds its way to La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, where it’s recorded in November 1991 by Ciccolini, one of the 16 pieces I’ve been listening to in August 2012 while the water’s running in the sink as I scrub and scour into the depths of a skillet that begins looking like one of Turner’s storms at sea as Debussy’s joyous Jersey idyll bursts forth from the Bose Wave sounding in the chiming trilling flux of demonically intense invention not unlike the “fantastic arrangements” and “shimmering sequences” that Debussy’s fellow student remembers hearing long long ago in the classroom. Next morning, already feeling worn out, not looking forward to a dreary errand, I get into my trusty four-wheeled stereo, put on the same CD (Piano Works, Vol. V) to a surefire energy source, Tarantelle styrienne (later simplified to Danse), some of the most exhilarating piano music ever written, and I’m revived in an instant, riding high, and what was a chore has become a mission.

Something Amusingly Else

Of course Debussy has much more to offer than morning euphoria and instant energy. Take one of the best-known and most-played of his compositions, Clair de lune, which begins in a state of tender hesitant beauty, builds to an emotional summit, and goes down like a sunset. It’s one thing to hear Ciccolini play it, and something amusingly else to see Spencer Tracy at the keyboard in Without Love, one of the lesser-known movies he made with Katherine Hepburn. If it had been Hepburn swooning elegantly over the keys, no big deal, but that’s Spencer Tracy tucking in the belt of his bath robe as he sits down to play. No ceremony, no airs, the most unceremonious of actors is making beautiful music as Hepburn listens transfixed on the stairs, in her bathrobe, about to dissolve into an amorous mist, just as my own mother did whenever my undemonstrative father played the same music.

The Anglophile

Debussy may not have spoken the language but, as Lockspeiser makes clear, he was thoroughly immersed in the culture of the British Isles, though it should be mentioned that Debussy was very much under the influence of France’s favorite American, Edgar Allan Poe, to the point of planning but never finishing operas based on The Devil in the Belfry and The Fall of the House of Usher. (In November 2009 Opéra Français de New York presented the enhanced remains.) Besides enjoying idylls in Jersey and Eastbourne with Emma Bardac, whom he married in 1908, Debussy hired an English governess for his daughter and was a steadfast admirer of English art (Turner, Whistler, the Pre-Raphaelites, William Morris, Walter Crane, Aubrey Beardsley, Arthur Rackham), poetry (Keats, Shelley, Swinburne), literature (J.M. Barrie, Oscar Wilde, Dickens, and above all Shakespeare). The original role of Mélisande in his opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, belonged to Mary Garden, a Scottish soprano with a voice he had “secretly imagined — full of a sinking tenderness” who sang “with such artistry” as he “would never have believed possible.” Perhaps the most whimsical indication of the extent of his devotion to things English is in Volume Two of the Preludes, the one titled Hommage to S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C. [Perpetual President-Member Pickwick Club]. He also composed preludes based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Peter Pan.

“Ever Higher”

“Anywhere out of the world” was Debussy’s half-facetious response to one of the questions (“Where would you most like to live?”) on a printed questionnaire from February 1889 included as an appendix in the first volume of Lockspeiser’s biography. Among Debussy’s more earthly enjoyments: reading “while smoking complex cigars” (les tabacs compliqués), the color violet; Russian cooking; and coffee. His favorite fictional hero and heroine were Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Rosalind. His idea of happiness: “to love,” his motto “Ever higher.”

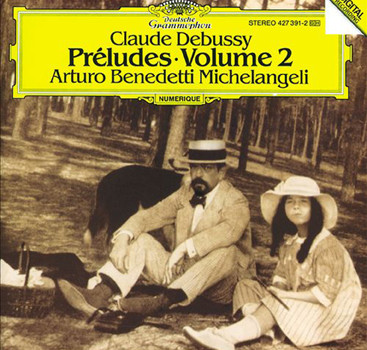

Twice married, Debussy had numerous affairs. Green-eyed Gabrielle Dupont, who can be seen in all her statuesque glory among the photographs in Lockspeiser’s book, attempted suicide when their ten-year relationship ended, and his first wife shot herself on the Place du Concorde after a letter from Debussy telling her that the marriage was over (she survived). That’s the composer’s 11-year-old daughter, Claude-Emma (Chouchou), sharing a picnic on the grass with her straw-hatted father in the photograph on the cover of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s 1988 recording of the Preludes. You can imagine something of the father-daughter relationship if you to go to “Debussy plays Debussy” on YouTube and listen as Debussy plays “Golliwog’s Cake-Walk,” from the Childrens Corner suite he wrote for Chouchou, whose smiles, he told a friend, “helped him overcome periods of black depression.” In a letter home, he writes of how sad he is “not to hear your songs and your laughter and all that noise which sometimes makes you an unbearable little person.” Before going into surgery in 1915, he tells his wife that she and Chouchou “are the only two beings who should prevent me from disappearing altogether.”

The Last Word

For Lockspeiser, Debussy’s child provides the most reliable eyewitness account of his death from cancer on March 25, 1918, as German artillery bombarded Paris. In a letter to her half-brother, she writes, “When I went back into the room Papa was sleeping and breathing regularly but in short breaths. He went on sleeping in this way until ten o’clock in the evening, and at this time, sweetly, angelically, he went to sleep for ever.” At the funeral, Chouchou did her best not to cry, for her distraught mother’s sake. “I saw him for the last time in that horrible box …. As I almost fell over I couldn’t kiss him.”

Chouchou herself had less than a year to live. Her death, during the diphteria epidemic, was thought to be due to an erroneous diagnosis.

Edward Lockspeiser’s biography was an invaluable resource that would not have been available but for the Princeton Public Library, which also had the Claudio Abbado Wiener Philarmonic recording of Pelléas et Mélisande, a hypnotic experience when listened to with headphones between midnight and three in the morning. I also consulted Debussy On Music, which I found at last year’s Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Book Sale.