Now’s The Time: Making History With Charlie Parker and Jerry Garcia

I consider life to be a continuous series of improvisations. —Jerry Garcia (1942-1995)

I consider life to be a continuous series of improvisations. —Jerry Garcia (1942-1995)

There’s too much in my head for this horn.

—Charlie Parker (1920-1955)

I am looking at a 12-inch Verve LP, Now’s the Time, the Genius of Charlie Parker #3, which is in the same dismal shape it was when the girl I married four years later unceremoniously presented it to me in San Francisco on my 24th birthday. “Bobby Petersen, the guy who gave it to me, stole it,” she said.

Not much of a birthday present, you may be thinking. In all fairness, the girl, who was 18 and in her first year at Berkeley, hardly knew me at the time. Strips of army-green friction tape had been clumsily applied to the entire top and bottom seams of the cover and another shorter piece was holding the spine together. Charlie Parker’s face, what you can see of it, has a cloudy, glazed-over look, though the original spotlight blue has sustained a certain luminosity in spite of the wear and tear. The vinyl is scuffed and scratched, but it plays fine, and the music is coming, after all, from a performer of such impenetrable charisma that the disc’s very flaws, its crackles and hisses, have an archival validity. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus tells Mr. Deasy history is “a shout in the street.” Now’s the Time says history is “a record with surface noise.”

By now I’ve sold or traded almost all my jazz vinyl, and I’ve got a CD of this album, so why am I hanging on to stolen merchandise in laughably bad shape with the name of the guy it was probably stolen from (“Wade November 1958”) written in blue ink on the upper right of the back cover? Just because it was my future wife’s first ever gift to me? Am I that sentimental?

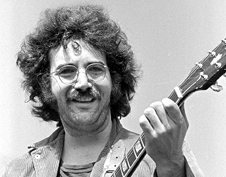

You bet I am. But even more, I’m looking for ways to tie together a column about two legends of American music, alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, whose 92nd birthday is today, and guitarist Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead whose 70th fell on August first.

The Petersen Connection

Early in his five-hour-long Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner and Charles Reich on January 20, 1972, Jerry Garcia recalls first getting together with Dead-bassist-to-be Phil Lesh and “this other guy named Bobby Petersen, who is like an old-time wine-drinkin’ convict post criminal scene, a great guy.” Blair Jackson’s Garcia: An American Life puts Petersen, along with Lesh and Garcia “and about two hundred other people,” at “a giant party dubbed the Groovy Conclave” that began on November 18, 1961, and went on for three days at a rambling Palo Alto “party house” known as the Chateau.

Meanwhile Petersen’s pal Phil Lesh had enrolled in the music department at Berkeley, where in addition to working as a volunteer engineer at KPFA, he helped the girl-who-gave-me-Now’s the Time with her homework for a physics class taught by Edward “Dr. Strangelove” Teller. Petersen most likely still had the record when he was hanging out with Garcia and Lesh and the Dead’s eventual music publisher Alan Trist. In Robert Greenfield’s Dark Star: An Oral Biography of Jerry Garcia, Trist recalls smoking grass with Petersen, Lesh, and Garcia, among others, at his house in Palo Alto (“my parents were away”), which happened to be in back of Ken Kesey’s cabin: “We got very stoned because we were young people whose systems were quite open. And we designed this fantasy of how we would like to be, where we would like to take all this beat stuff.” It’s not much of a stretch to imagine that during the designing of this fantasy, or during “the giant party” in November, my destined-to-be-24th-birthday copy of Now’s the Time was playing, either in the back or foreground, for this was the period, before Dylan and the Beatles, when the music of choice for stoned “young people” with “open systems” was jazz, along with blues, bluegrass, and folk, and the player of the hour and the era was Charlie Parker.

Years later, in his introduction to Alleys of the Heart: The Collected Poems of Robert M. Petersen (published in 1988, a year after Petersen’s death at 51), Alan Trist mentions the lyrics Petersen wrote for the Grateful Dead (“New Potato Caboose,” “Unbroken Chain,” “Pride of Cucamonga”) and describes the poet as “one true voice of a generation” who hopped the freights, played jazz saxophone, served time, “practiced freedom” and “bridged the beat scene of San Francisco to the rock era, like his sometime companion Neal Cassady.” In “Fern Rock,” one of the longest poems in Alleys of the Heart, Petersen describes Jerry Garcia “bending the frames of / reality … reaching into that system / pulling out dream after dream.”

The Vinyl Connection

Such then is the provenance of my well-traveled birthday gift of Bobby Petersen’s stolen copy of Now’s the Time, which I’ve just been listening to in its original state, scuffs and scratches and taped-up sleeve notwithstanding, and after the first three tracks, I had to run up here to the “keyboard” — which I put quotes around because the only keyboard worth serious mention after listening to this record is Hank Jones’s, a subtle, solid, and ebulliently inventive complement to the brazen brilliance of Charlie Parker, superbly driven in turn by Max Roach’s drumming and Teddy Kotick’s bass.

One of the virtues of returning to the primal vinyl after a long absence (our only turntable has been my son’s domain for 15 years) is the sheer size and depth of the sound compared to that of a compact disc. When you listen to a record like this one, you’re closer not only to the music and the moment of its making, but to all the previous playings, from the first needle-in-the-groove moment in 1958 when “Wade,” the guy who wrote his name on the back, set the jazz genie free. Close your eyes, open your imagination, and you may hear, as on an extended voice mail playback, the various exclamations of delight and fanciful stoned dialogues of previous listeners at those Palo Alto parties Wade may have been attending when my wife’s long-ago friend Bobby P. ripped him off.

Or maybe Petersen lied about stealing the album in order to impress the impressionable Berkeley freshman he was generously introducing to Charlie Parker. As for the sorry condition of the thing, inside and out, the defects, like I said, are part of the historical profile, as are Bill Simon’s lengthy liner notes on the back of the worn and faded sleeve additionally marred by grease spots and the yellowish imprint left by years of sweaty-handed handling, not to mention an informational defect that has Al Haig and Percy Heath playing piano and bass on the first six tracks, from December 30, 1952 (they play on the last six, from the July 30, 1953 session). As for the surface noise, it’s only there for Bird to blow through when Jerome Kern’s “The Song Is You” explodes from the speakers, followed by two numbers named for children, the first, “Laird Baird,” a sassy and playful blues for Parker’s son Laird and the second, for his stepdaughter Kim, what else but “Kim,” a flight of fairytale fancy on the changes of Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.”

The Kern Connection

While several Jerome Kern standards were in Parker’s repertoire, notably “All the Things You Are” (reborn as “Bird of Paradise”), the composer’s association with Jerry Garcia began at birth when his father, a clarinetist and saxophonist who admired Kern, named him Jerome John Garcia. Students of Garcia’s improvisations with and without the Dead might be able to find instances where he quotes some melodic fragment of his namesake’s music, but the most obvious recognition of the connection comes in a recording of Kern’s “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” on the soundtrack album for Wayne Wang’s film Smoke, released two months before Garcia’s August 9, 1995 death. In retrospect, the video, which can be seen on YouTube, becomes a playful, quirky swan song, with a seated, Buddha-benign Garcia performing while a sexy earth angel in the form of Ashley Judd looks on, making love to the moment. Smiling just about all the way, Garcia appears in fine fettle, his playing bell-clear, as he performs an atypically lively version of one of the great ballad melodies of American popular music. In the last image, as the smoke fades, Jerome John Garcia sits all alone in the rear of the deserted night club.

The Connection Connection

Unfortunately, the most obvious parallel between Charlie Parker and Jerry Garcia is in the Faustian role hard drugs played in each man’s life. There’s the familiar quote from a doctor who upon examining Parker said that at the age of 33 he had the body of a man twice that age. Something similar was said of Garcia at 53.

Since it would take more listening than I have time for, and a lot more thought and knowledge, I won’t presume to make comparisons between these two masters, beyond wishing for a front row seat at the concert in music heaven where Bird sits in with the Dead, joining Garcia in mid-flight during a performance of “Dark Star” like the one on Live/Dead where you know he’s venturing into regions not unlike the “realms of gold” Charlie Parker traveled in.

Reading the guitar.com and Rolling Stone interviews with Garcia, I found a number of places where he said things that might have been said by or about Charlie Parker, for instance, “I consider life to be a continuous series of improvisations …. Because being high, each note, you know, is like a whole universe. And each silence. And … all of a sudden we find a certain kind of feeling or a certain kind of rhythm and the whole place is like a sea and it goes boom…boom …boom, it’s like magic and … you discover that another kind of sound will like create a whole other, you know ….”

He didn’t finish the sentence, and no need. All the better, in fact. Let it be “a whole other —.” Not that he was ever at a loss for words. Speaking of another musician, Garcia once said that “nobody has come up to the state that he was playing at — that whole fullness of expression, the combination of having incredible speed and giving every note a specific personality.” He was referring to Django Reinhardt, but he could have been talking about Charlie Parker — and Jerry Garcia.