Mystery Guest Marcel Proust Makes His Presence Felt in Atget/Friedlander Show

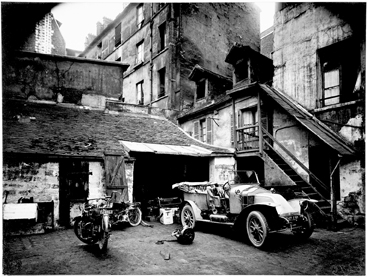

COUR, 7 RUE DE VALENCE: On display in “Two Views: Atget & Friedlander” through March 10, Eugène Atget’s photograph, printed by Berenice Abbott, is from “Eugène Atget Portfolio 1922,” printed 1956. Gift of David H. McAlpin, Class of 1920. (Courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum)

The mind-finger presses the release on the silly machine and it stops time and holds what its jaws can encompass and what the light will stain.

—Lee Friedlander (1934—)

These are simply documents I make.

—Eugène Atget (1857-1927)

No one knows who coined the phrase, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” It might have been an American newspaper editor in 1911 or it may go all the way back to Confucius. If you visit the Princeton University Art Museum’s new photography exhibit, “Two Views: Atget & Friedlander,” you’re almost sure to hear it or think it, but there’s a mystery guest in Atget’s Paris and Friedlander’s America who renders the old adage meaningless, turns it on its head, blows it to the moon. Depending on which translation of the four thousand-plus pages of Remembrance of Things Past (À la recherche du temps perdu, also translated as In Search of Lost Time) you’re referring to, Marcel Proust’s multi-volume work contains somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,200,000 words, any number or combination of which are worth a thousand pictures. You need more than mathematics to comprehend the magnitude of Proust (1871-1922). Walter Benjamin describes a “Nile of language” that “overflows and fructifies the regions of truth.” Virginia Woolf admits that her “great adventure is really Proust …. What remains to be written after that? One has to put down the book and gasp.”

A single sentence by Proust contains a quantity of phenomena even the most accomplished photographic artists would be hard put to keep up with, not to mention the translators E.M. Forster imagines confronting one such sentence, which “begins quite simply,” then “undulates and expands, parentheses intervene like quick-set hedges, the flowers of comparison bloom, and three fields off, like a wounded partridge, crouches the principal verb, making one wonder as one picks it up, poor little thing, whether after all it was worth such a tramp, so many guns, and such expensive dogs.”

Looking for Partridges

Besides the edition of In Search of Lost Time (2000) illustrated by Atget’s photography, there’s A Vision of Paris,in which Proust’s words accompany Atget’s images. Although the pairing makes decorative sense, Atget would have assembled his Paris no less memorably and selectively had Proust never existed. On the other hand, in introducing Lee Friedlander, Photographs (1978), Friedlander feels close enough to Proust’s way of reimagining reality to quote in full a sentence from the master every bit as far afield as the one Forster’s word picture of hedges and flowers is describing. Here it is in all its Proustian glory (see if you can find the “partridges”):

“Apart from the most recent applications of the art of photography — which set crouching at the foot of a cathedral all the houses which, time and again, when we stood near them, have appeared to us to reach almost to the height of the towers, drill and deploy like a regiment, in file, in open order, in mass, the same famous and familiar structures, bring into actual contact the two columns on the Piazzetta which a moment ago were so far apart, thrust away the adjoining dome of the Salute, and in a pale and toneless background manage to include a whole immense horizon within the span of a bridge, in the embrasure of a window, among the leaves of a tree that stands in the foreground and is portrayed in a more vigorous tone, give successively as setting to the same church the arched walls of all the others — I can think of nothing that can so effectively as a kiss evoke from what we believe to be a thing with one definite aspect, the hundred other things which it may equally well be since each is related to a view of it no less legitimate.”

The foremost partridges that Proust’s “hunting party” of prose has been deployed to shoot down are the verb “bring”andthe “kiss” that occasioned the whole fabulous outing in the first place. This is a kiss the narrator, Marcel, has been longing for, dreaming of, since childhood. When he finally plants his lips on Albertine’s cheek, the world turns over, the city of Florence is vigorously realigned, rebuilt, repainted, above all seen — much as an inventive American photographer chooses to see a world unencumbered by rules of time and space and logic.

Stroll through Friedlander’s half of the “Two Views” exhibit and there’s no doubt how closely the photographer’s vision coheres with and reflects Proust’s approach to time, place, and memory. It’s almost as if the theatre of Friedlander’s imagery were shaped according to the stage directions provided in that exhilaratingly interminable prelude to a kiss, spaces contracted, disparate elements brought together, structures displaced and thrust into new formations, along with the urban horizons, New Orleans, Cincinnati, Chicago, Kansas City, compressed within the spans of bridges, in the “embrasure” of windows and mirrors, or “among the leaves of a tree.”

Stunt Man

The centrality of cars to Friedlander’s art would seem to set his work apart from both Atget and Proust. It’s not the car as subject that attracts him so much as the car as force, catalyst, enclosure, and high-octane photographic accessory. In Friedlander’s Hillcrest, New York (1970) you sit in the driver’s seat watching automobiles moving in opposite directions, at clumsy angles, against multiple backgrounds, where a distant human figure is walking downhill while still more distant human figures occupy a bench, as if in another dimension, everything expressing degrees of impediment and displacement, the template of a degraded reality that Friedlander is attacking like a stunt man driving through a plate glass window.

I wonder if Friedlander knew about Proust and fast cars. According to William C. Carter’s biography, Marcel Proust: A Life (Yale 2000), the novelist enjoyed speeding around Normandy in a red taxi with a professional driver (“It’s like being shot out of a cannon”). Too bad Friedlander couldn’t be there to photograph “the distant spires” Proust saw “appear and disappear against the horizon in constantly shifting perspectives” as he “marveled at the phenomenon of parallax and relativity so keenly felt in an automobile.”

Concerning Atget, it’s worth noting that the brightest image in his predominantly sepia portion of the “Two Views” exhibit (Cours, 7 rue de Valance) is centered on a resplendent Renault touring car. In The World of Atget: Modern Times (Museum of Modern Art 1985), a note by editor John Szarkowski says that because Atget preferred to see Paris on his own terms (“I can safely say that I possess all of old Paris”), he “withheld recognition of the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe” and was equally reluctant to focus on automobiles — at least until he discovered that particular Renault, in Szarkowski’s words, “as handsome and strange as a heathen conqueror, in the homely, decaying courtyard.”

More important than the car, however, is the courtyard. Friedlander would appreciate the natural convergence of forms and angles (no need to do any fancy photographic shape shifting), and the same could be said of Proust, who would conjure wonders of literary art from this “homely” courtyard’s wealth of surfaces, the texture of the sloping roof of the garage and the masonry, the yawning dormer windows of the structure opposite with its stairway sheltered by yet another sloping roof. There are at least six or seven suggestively weathered canvases on which paintings could be imagined by the writer who turned a “patch of pale yellow” on a wall into “something rich and strange” in Remembrance of Things Past.

The End of Life

The month before Atget’s view of the “decaying courtyard” dated June 1922, Proust ventured outdoors for what may have been the last time (he died in November), his goal the Jeu de Paume, where one of his favorite paintings, Vermeer’s View of Delft, was on display. Even before he reached the street, he was feeling faint and needed help from a friend, who escorted him to the museum and the Vermeer and later said that he was shaken by the outing. Proust’s shaky last viewing of the Vermeer inspired one of the most celebrated and haunting sequences in his work: the death of the writer, Bergotte, who is also feeling unwell as he gazes into the View of Delft at the “little patch of yellow wall” that was “like some priceless specimen of Chinese art, of a beauty that was sufficient in itself.” His dizziness increasing, he fixes “his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious little patch of wall.” He finds himself thinking, “That’s how I ought to have written,” that he ought to have made his language “precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall.” Repeating it to himself, “Little patch of yellow wall, with a sloping roof, little patch of yellow wall,” he sinks down on to a circular settee, thinking it’s “nothing, merely a touch of indigestion” when a “fresh attack” strikes him, he rolls from the settee to the floor, and dies.

The long paragraph pondering spiritualism and other worlds that follows the moment of Bergotte’s death is, according to Carter’s biography, as close as Proust ever comes to “declaring some sort of belief in the afterlife.” The writing is also noticeably less difficult than the prose Forster playfully improvised on and Friedlander used for a preface. The paragraph ends with a rather flat summary, for Proust, “So that the idea that Bergotte was not dead for ever is by no means improbable.” Proust improves on the same idea after describing Bergotte’s funeral: “They buried him, but all through that night of mourning, in the lighted shop-windows, his books, arranged three by three, kept vigil like angels with outspread wings and seemed, for him who was no more, the symbol of his resurrection.”

Proust will experience a resurrection of sorts in 2013. It was 100 years ago, November 14, 1913, that Swann’s Way, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past was published in Paris. The Morgan Museum and Library’s upcoming commemorative exhibit, “Marcel Proust and Swann’s Way,” begins on February 15.

Curated by Peter C. Bunnell, photography curator emeritus at the Princeton University Art Museum and former curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, “Two Views” will run through March 10.