Living in Dostoevsky: Joseph Frank’s Acclaimed Biography Was Born in Princeton

By Stuart Mitchner

In Beat Generation scripture Carl Solomon asks Allen Ginsberg, “Who are you?” to which Ginsberg instantly replies, “I’m Prince Myshkin,” asking the same of Solomon, who says, unhesitatingly, “I’m Kirilov.” The two poets identifying themselves as the holy fool and the nihilist from The Idiot aren’t delusional, they’re just living in Dostoevsky. So was Jack Kerouac, who called him Dusty, and so are generations of readers, who, like actor/writer Stephen Fry, put him foremost among those great writers who were “not to be bowed down before and worshipped, but embraced and befriended,” and who “put their arms around you and showed you things you always knew but never dared to believe.”

It Began in Princeton

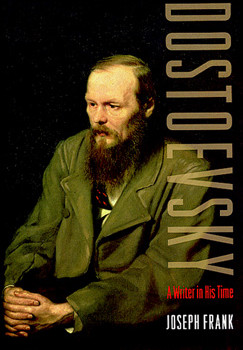

Award-winning Dostoevsky biographer Joseph Frank (1918-2013), who died in Palo Alto on March 3, wrote the first volumes of his magnum opus in Princeton, where he lived at various times during the 1950s and from 1966 to 1985. Early in his preface to Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time (2010), the one-volume edition of the five-part work published by Princeton University Press, Frank pays his respects to “the much lamented and gifted novelist” David Foster Wallace, “the most perceptive reader of my first four volumes.” The only sentence quoted from Wallace’s essay, however, is the one in which he contrasts Frank’s approach to that of James Joyce biographer Richard Ellman, who “doesn’t go into anything like Frank’s detail on ideology or politics or social theory.”

Enter David Foster Wallace

Intrigued by the appearance of the Generation X author of Infinite Jest in the preface to what was for all purposes the swan song of Frank’s great work, I sought out the essay in question, “Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky,” which originally appeared in 1996 in the Village Voice Literary Supplement as “Feodor’s Guide” and can be found in Wallace’s 2005 collection, Consider the Lobster.

The first thing that caught my attention in Wallace’s quirky, refreshingly candid, and highly personal essay was the way his presentation of the genesis of Frank’s book clarified Princeton’s place in the story, something the New York Times’s notably skimpy obituary failed to do: “In 1957 one Joseph Frank, then thirty-eight, a Comparative Lit professor at Princeton, is preparing a lecture on existentialism.” The text Frank is “working his way through” is Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, “a powerful but extremely weird little novel” whose protagonist’s “disease” is “a blend of grandiosity and self-contempt, of rage and cowardice, of ideological fervor, and a self-conscious inability to act on his convictions.”

After describing how Frank comes to realize that Notes from the Underground and its Underground Man “are impossible really to understand without some knowledge of the intellectual climate of Russia in the 1860s,” Wallace caught my attention again by expressing concern for Joseph Frank’s physical health: “The amount of library time he must have put in would take the stuffing out of anybody, I’d imagine.” He’s responding to the photo of Frank on the back jacket of The Miraculous Years, 1865-1871, observing that “he’s not exactly hale, and probably all serious scholars of Dostoevsky are waiting to see whether Frank can hang on long enough to bring his encyclopedic study all the way up to the early 1880s.”

Of course Frank, who must have been amused by the younger writer’s solicitude, not only hung on until 2002 when he delivered the final volume, The Mantle of the Prophet, 1871-1881, he was still around eight years later for the single-volume edition that gave him an opportunity to acknowledge “the much lamented and gifted novelist” who, a victim of chronic depression, had taken his own life in 2008.

What Wallace Needs

After getting marginally personal on the subject of Frank’s photograph, Wallace goes all the way to the other side of objectivity with the first of a series of intimate asides so much in the style of Notes from the Underground that if it were not for the double asterisks surrounding the paragraph, you might almost think he was quoting from Dostoevsky. By now Wallace definitely has my attention. What’s going on? Frank would surely have been asking the same question even as he recognized the obvious resemblance between Wallace’s manner and that of the Underground Man. Meanwhile, readers who think of Wallace as an ironist would be rolling their eyes or at least scratching their heads. In a 1996 interview with Laura Miller, Wallace mentions the conflict between “the part of us that can really wholeheartedly weep at stuff, and the part that has to live in a world of smart, jaded, sophisticated people, and wants very much to be taken seriously by those people.”

No doubt about it, the intimate questionings inspired by Dostoevsky’s Notes were not written for “those people.” Asking himself whether he’s “a good person,” Wallace wonders does he even “want to be a good person” or does he only want to “seem like one,” and does he ever actually know whether he’s morally deluding himself? Another aside on the meaning of faith is no less naked, for “Isn’t it basically crazy to believe in something there’s no proof of?” or “is needing to have faith sufficient reason for having faith? But then what kind of need are we talking about?” At this point, it begins to seem that Wallace is no longer writing for the general reader but is deliberately, “wholeheartedly” laying himself open for Frank’s benefit: “Is the real point of my life simply to undergo as little pain and as much pleasure as possible? Isn’t this a selfish way to live? Forget selfish — isn’t it awfully lonely?” Then: “But if I decide to decide there’s a different, less selfish, less lonely point to my life, won’t the reason for this decision be my desire to be less lonely, meaning to suffer less overall pain?”

What’s striking about these heartfelt soliloquies is the sense that Wallace feels the closest he can come to communicating with Dostoevsky is through Frank since it’s Frank who is most intimately committed to the life and the work, so it’s to Frank that Wallace bares his soul. A decade later, when the biographer picks up the essay again while working on a preface for the one volume edition in the all but immediate aftermath of the young writer’s suicide, how could he not help but see a foreshadowing of Wallace’s fate in the naked need expressed in those anguished asides?

Two Wives

Any writer who depends on a partner for editorial and moral support will have a special interest in the relationship between Dostoevsky and his second wife, Anna, who came to him as a stenographer and a sympathetic reader. At the age of 15, as Frank relates, Anna had “tearfully pored over installments of The Insulted and the Injured,” with special sympathy for “the tenderhearted but hapless” narrator, whose “deplorable fate” she identified with “that of the author.” Frank suggests that even before Anna became Dostoevsky’s wife, she was an invaluable aide to his life and work: “Encouraged by Anna’s cool determination, Dostoevsky settled down to a regular routine … was much calmer … and became more and more cheerful as the pages [of his short novel, The Gambler] piled up.”

After acknowledging the “arduous” two-year task accomplished by editor Mary Petrusewicz in compressing five volumes into Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time, Joseph Frank takes the customary conjugal statement of gratitude to another level. Previous volumes had acknowledged Marguerite Straus Frank’s “linguistic and literary sensitivity,” and a draft of the fifth volume was actually withdrawn and rewritten in the light of her suggestions. Ahead of the one-volume edition, Frank explains that because she was dissatisfied with his treatment of “perhaps the most complex of all the female characters in Dostoevsky’s novels, the beautiful and ill-fated Nastasya Filippovna of The Idiot,” his wife had “so much altered and enriched” his own initial views that he “asked her to express them herself,” thus the pages devoted to Nastasya Filippovna in Dostoevsky: A Writer in his Time, “come from her pen.”

Marguerite Frank explained the difference of opinion in a 2009 interview with Cynthia Haven in the Stanford Report. “Joe’s not interested in Nastasya — he’s interested in the ‘Idiot,’” meaning Prince Myshkin. While Dostoevsky, like other great writers of the period, was “fascinated by fallen women,” Natasya is no fallen woman: “She’s an absolutely pure victim.”

Joseph Frank’s first book, The Widening Gyre: Crisis and Mastery in Modern Literature, was published in 1963 by Rutgers University Press, whose then-director William Sloane encouraged him to edit the Selected Letters of Fyodor Dosteovsky, which was eventually published by Rutgers in 1986. Though Frank taught at Rutgers, the definitive appointment (not counting his 1953 marriage to Marguerite) came in 1954 when he arrived in Princeton to give the Christian Gauss Seminars in Criticism, a program he would later direct for 18 years. In 1976, Princeton University Press brought out the first volume of the biography, The Seeds of Revolt. 1821-1849 (1976), which won both the James Russell Lowell Prize of the Modern Language Association and Phi Beta Kappa’s Christian Gauss Award in criticism. Volume Two, The Years of Ordeal, 1850-1859, won the National Critics Circle Award, the first Princeton University Press book to receive that honor.