In the Month of His Birth, A Little Touch of Shakespeare in the Night

By Stuart Mitchner

Shakespeare, he’s in the alley with his pointed shoes and his bells ….

—Bob Dylan

You read me Shakespeare on the rolling Thames, that old river poet who never, ever ends …. —Kate Bush

Whatever, whoever he may be, Shakespeare is everywhere. Locally, he was just the subject of an early birthday celebration at the library. Universally, besides being caricatured in Shakespeare in Love (1998) and deified in Berlioz’s Memoirs (1865), he’s in Dylan’s alley “stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis blues again,” whispering poetry in Kate Bush’s elegant ear in “Oh England My Lionheart,” and now and forever, or so I like to think, he’s moving “with sweet majesty” among us like King Henry among his troops the night before the battle of Agincourt in Laurence Olivier’s film, Henry V.

If I were asked this week’s Town Talk question about a favorite work by Shakespeare, I’d give the lazy, easy, obvious answer. But Hamlet was more than a favorite, it was the great insurmountable mist-shrouded summit of graduate school, and by the time I bowed out of the program, I felt like the pilgrim in the old joke about the quest for the meaning of life who finally finds the master’s cave and throws himself at the enlightened one’s feet only to be told “Life is just a bowl of cherries, my son,” except instead of cherries the answer is Shakespeare. Just Shakespeare.

Berlioz knew. The great French composer’s avowed master was not a man of music but a man of words, of whom he wrote after the death of Harriet Smithson, the Irish actress he fell in love with watching her play Juliet and Ophelia: “Shakespeare! Shakespeare! I feel as if he alone of all men who ever lived can understand me, must have understood us both; he alone could have pitied us, poor unhappy artists, loving yet wounding each other. Shakespeare! You were a man. You, if you still exist, must be a refuge for the wretched. It is you who are our father, our father in heaven, if there is a heaven.”

Besides being the subject of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, the actress inspired the love scene from his choral symphony Roméo et Juliette that Toscanini once said was “the most beautiful music in the world.”

In Love

When I was lost in graduate school Elsinore, prowling in and out of the nooks and crannies of Hamlet’s castle, I had a fantasy where, very very late at night, I would zone in on one small glowing window, creeping close enough to peer over Shakespeare’s shoulder as he writes, watching the words being shaped on foolscap in ink as fresh as the moment. My fantasy came to life in Shakespeare in Love, at the end where the young poet is shown scribing two words in Shakespearean script at the top of a fresh white page, “Twelfth Night,” the play he’s writing for and about Viola, as Berlioz wrote for and about Harriet Smithson. Viola’s his muse, the love of his life, who smites him, as Smithson did Berlioz, when she’s playing Juliet. Sure, it’s only a high-tech Hollywood facsimile of the moment of creation, but that doesn’t make it any less thrilling to see on screen, the perfect ending for an unashamedly imperfect film, a brash, broad, wildly romantic, never uncolorful journey. After the words, “Scene One: A sea coast,” are formed, there’s a closeup of the playwright’s hand, thumbnail black with ink, scribing “Viola,” the image fading but still visible as his Viola appears striding along a distant shore, seemingly given life and motion by the movement of his pen.

A great many people, old and young, left Shakespeare in Love feeling good about life and Shakespeare and half in love with Gwyneth Paltrow. Although I had doubts about Joseph Fiennes in the title role, he played it with passion and panache, and who could complain about Geoffrey Rush’s vivid comic turn as Henslowe except maybe Henslowe? Paltrow’s lovely, spirited Viola won the Best Actress Oscar as much for sheer presence as for her performance; it’s her energy, charm, and beauty that gives the film its glow. And on top of that, this piece of commercial bardolatry scored at the box office and won seven Academy Awards, also including Best Picture. “Best” was a poor choice for Paltrow. It should have been “Most Radiant.”

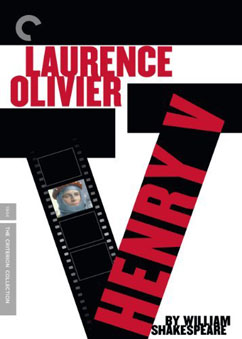

However, having just seen Shakespeare in Love for the first time in 15 years, I find that the glow has faded somewhat, and the film now and then seems forced, sloppy, bogus, and too amused with itself (as in the nasty-kid-who-grew-up-to-be-John-Webster gag). But then I came to it the day after seeing a vastly superior work with a similar subject and setting. Resplendently remastered in the Criterion DVD, Laurence Olivier’s Henry V makes the newer film’s charm, color, warmth, and Shakespearean ambience look one-dimensional.

Higher Ground

When Olivier was advised to film Henry V in “battledress,” — this being wartime, with D-Day looming — he said, “No, it’s got to beautiful.” Given the prevailing conditions — the need to shoot it in Ireland where sufficient numbers of men (650) and horses (150) were available and the sky was free of Luftwaffe planes on their way to the bombing of London — Olivier was too busy to know that his film would develop into one of the most beautiful ever made. Henry V also provided the Shakespeare of film reviewers, James Agee, with one of the great assignments of his life when it opened in the U.S. in the spring of 1946, a year and a half after its inspirational 1944-45 run in wartime England.

In his April 8, 1946 TIME review, which included a cover profile of Olivier, Agee was not as circumspect as he would be months later in his two-part article in The Nation. Under the one-word heading, “Masterpiece,” the review begins, “The movies have produced one of their rare great works of art.” No one distrusted freely dispensed superlatives more than Agee, but he must have known he was making journalistic history. The purpose of the first part of his Nation review was “getting off his chest” all he “could possibly find to object to.” In the TIME review, Agee pulls out the stops: “At last” there has been “brought to the screen, with such sweetness, vigor, insight, and beauty that it seemed to have been written yesterday, a play by the greatest dramatic poet who ever lived,” “a magnificent screen production,” “one of the great experiences in the history of motion pictures … a perfect marriage of great dramatic poetry with the greatest contemporary medium for expressing it.”

It’s worth noting that Henry V arrived in America at a time when Shakespeare was considered box office poison after the financial debacles of elaborate major-studio productions like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, As You Like It, and Romeo and Juliet. Between the complaints of censors worried about suspect references to God and exhibitors concerned with the film’s excessive length, the powers that be in the States seemed to be conspiring to tarnish Olivier’s triumph, but to no avail, thanks in great part to Agee’s send off in TIME, the most widely read magazine in America.

Agee is still the only writer I know of whose weekly film reportage endures as literature. Surely no one but he would make the effort to envision a future moment when “after many more seeings,” the setting and the casting, “which now seem as nearly perfect as I have ever seen in a film,” might seem “perhaps … a little predictable,” and where “Renée Asherson’s performance as the French princess, which now seems to me pure enchantment, will … look a little coarsely coy.” In fact, Agee is only cleverly covering all the bases, as the next sentence makes clear: “But if this time ever comes I fear also that I will have lost a certain warmth of spirit, and capacity for delight, which the film requires of those who will enjoy it, and which it asks for, and inspires, with a kind of uninsistent geniality and grace which is practically unknown in twentieth century art, though it was part of the essence of Shakespeare’s.”

In addition to indicating why Olivier’s Henry V will never cease to delight him while subtly prescribing the perceptual virtues that make an audience worthy of it, Agee is describing qualities in Shakespeare like those that Berlioz is responding to in his prayerful cry from the heart to the one who “alone of all the men who ever lived” could understand him.

Among the numerous instances in the plays and sonnets where Shakespeare’s humanity has been cited and celebrated, Henry V contains a passage in which the author not only seems to be speaking to us but visiting us, moving among us, a monarch of art in the guise of a king passing anonymously among his troops, a presence at once human and divine. On the night before the Battle of Agincourt, the film delivers a storybook image showing the lights of the French and English camps burning opposite one another like two encampments in a world of night as the chorus — read by Leslie Banks as if Shakespeare were truly speaking through him — sets the scene: “Now entertain conjecture of a time/When creeping murmur and the poring dark/Fills the wide vessel of the universe.”

The image held onscreen for the time it takes to speak those richly resonant words lives and breathes with its own mysterious beauty and suffuses the scene that follows, as the soldiers “by their watchful fires/Sit patiently and inly ruminate/The morning’s danger.” Borrowing a cloak to disguise himself, “the royal captain of this ruin’d band” walks from “watch to watch, from tent to tent … with cheerful semblance and sweet majesty,” so that “every wretch, pining and pale before,/Beholding him, plucks comfort from his looks.” As Olivier’s disguised king brings to life the words of the chorus, he embodies the virtues Agee finds in Shakespeare, “geniality and grace” and “sweetness, vigor, insight, and beauty.” He also has the benefit of one of the most endearing lines in literature, spoken like a father to all the children of the world as the chorus continues, with reference to “A largess universal, like the sun,/His liberal eye doth give to every one,/Thawing cold fear,” as “mean and gentle all/Behold, as may unworthiness define,/A little touch of Harry in the night.”

And a little touch of Shakespeare, still and forever moving among us.