Doing “Gatsby”: F. Scott Fitzgerald and the Man With the Beautiful Shirts

By Stuart Mitchner

The Garden Theatre was filled to overflowing for the Friday evening showing of Baz Luhrman’s big, jazzy, flamboyantly picturesque improvisation on The Great Gatsby (see review in this issue). People were seated on the steps of the aisle between the stadium seats. You got the feeling half the Princeton student body was there, along with a goodly number of teenagers from the area schools. Most nights at the Garden or Montgomery, particularly when the film is a literary classic as was recently the case with Anna Karenina, you see very few people under 30 or even 40. Or 50. Or, well, you get the idea.

According to the “Arts, Briefly” column in Monday’s New York Times, Gatsby took in $51.1 million over the weekend, second to Iron Man’s $72.5 — “an astounding result for a period drama” that received, at best, mixed reviews. Only 33 percent of ticket sales were for the 3-D version. Apparently the word of mouth about Gatsby’s flying shirts was less than enthusiastic. If you’re interested, those “beautiful shirts” can all be had at Brooks Brothers, along with the regatta blazers and boater hats, bow-ties, and shawl-collar sweaters. According to Adweek, the film’s 500-piece wardrobe was modeled on Brooks’ early 1920s catalogue. It’s also reminiscent of the faux sixties marketing boom created when Mad Men was the rage, with cool, elegant Don Draper at the center, a self-created mystery man who has more than a little in common with Fitzgerald’s “elegant roughneck,” Jay Gatsby.

Anyway, with a score as ecstatic and multi-dimensional as Luhrman’s, who needs 3-D? Depending on your stamina, the film’s pounding over-the-top blend of rap and Gershwin, Lana Del Ray and Bryan Ferry, can either kill you or cure you. My advice is to forget what’s being done to Fitzgerald’s original and go along with the sights and sounds, ride the music, get drunk on the spectacle, and don’t worry about little things like the absurdity of Nick Carraway in a sanitorium writing Fitzgerald’s book as a form of therapeutic rehab. If anyone is Fitzgerald. it’s the man with all the beautiful shirts.

The spectacular score alone is more than enough to put the 2013 Gatsby on a level above the previous versions — which isn’t saying much when you consider the quality of the competition.

Herbert Brenon’s 1926 silent Gatsby with Warner Baxter is presumed lost, probably just as well. If you look online, you can see the preview, which features the novel’s signature vision, the immense billboard eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleberg. All the films are faithful to it in their fashion but fall short of Fitzgerald’s “blue and gigantic” eyes with retinas “one yard high” looking out of “no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose.”

The first sound version of Gatsby didn’t hit the screens until 1949, some 20 years after the talkies were born. For some unfathomable reason, Paramount gave the project to Elliott Nugent, a director of comedies who had just finished filming Mr. Belvedere Goes to College. The best thing about this version, which can be seen in full on YouTube, is Alan Ladd. The only Gatsby of the lot who can say “old sport” as if it came naturally, Ladd makes his first appearance in a moving car tommygunning a rival in case you doubt where he’s coming from, and if you think he’s going to be vanquished by Tom Buchanan, Daisy’s brute of a husband at the end, as are all the other Gatsbys including the real one, you don’t know Alan Ladd. When Tom threatens to break his neck, this Gatsby stands his ground (“I wouldn’t do that if I were you. I’m pretty good with or without gloves”) and leaves the scene with Daisy even more devoted to him than she already was. But he gets all noble, Hollywood style, at the end as Paramount pays contemptible obeisance to the Code by making him apologize for his evil ways.

The Gatsbys from 1974 and 2000 (a television movie) are both uninspired ventures, Jack Clayton’s Robert Redford/Mia Farrow debacle having been famously compared to a dead body by Vincent Canby.

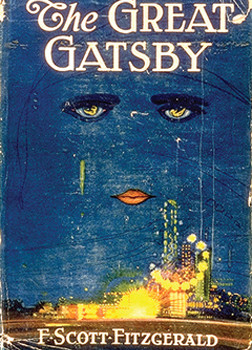

The Face of the Book

Now that we know the film had a strong opening weekend, what has been the financial fate of a novel about a man spending a fortune to win a girl whose voice is “full of money?” In 1925, given the popularity of Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise, sales and reviews were disappointing. In 2013, however, the Gatsby gold mine is working overtime. The paperback sells 500,000 copies a year, twice that many this year thanks to the film. Worldwide, the numbers approach 25 million in 42 languages, according to USA Today. In the rare book market, where literary stature makes all the difference, a copy of the first edition of The Great Gatsby sold at auction in 2009 for $182,000. Like all modern first editions, it attracts serious money only if it’s wrapped in its original dust jacket. The most you can get for a fine copy of an unjacketed Gatsby is a mere $8,000. With this novel, however, you have a double dose of value, for the Gatsby dust jacket is the Hope Diamond of cover art, the rarest and most celebrated in all literature.

When Fitzgerald had his first look at the cover image the summer before the novel’s April 1925 publication date, his excitement was such that he fired off an urgent command to his editor Max Perkins not to “give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it into the book.” He’s referring, of course, to the novel’s single most famous image, those giant billboard eyes that, “dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.”

Having seen the fascinating face that his work-in-progress would reveal to the world when published, Fitzgerald lets himself go and declares in the letter’s next sentence, “I think my novel is about the best American novel ever written.” It’s the sort of famous-last-words boast that even a writer less superstitious than Fitzgerald might want to take back. But the brilliant image has reinforced his enthusiasm for the brilliance of his conception. He knows he’s struck gold.

Scribners paid Francis Cugat $100 for the visionary cover art that captivated Fitzgerald. Not much is known about the artist except that he was the older brother of bandleader Xavier Cugat and that he worked in Hollywood as a technicolor consultant on number of films, including John Ford’s The Quiet Man. The eyes in Cugat’s image evoke Gatsby’s inspiration, his love and his doom, Daisy Fay Buchanan, “whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs … sad and lovely with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright passionate mouth.” It isn’t just that Cugat has shone a light on one of the visions haunting the heart of the novel, he’s found a way to visualize Daisy as Gatsby imagines her — the “colossal vitality of his illusion” that “had gone beyond her, beyond everything. He had thrown himself into it with a creative passion, adding to it all the time, decking it out with every bright feather that drifted his way.”

Again, the character capable of Fitzgerald’s conception isn’t Nick Carraway, it’s the man with the beautiful shirts. And if you have any doubt about where Gatsby’s “creative passion” is actually coming from consider the needless urgency of Fitzgerald’s message about the cover art, as if his editor really might let some other Scribner novelist snap it up. Fitzgerald is claiming possession of the treasure, it’s his, all his; and he’s already put it to use.

Gatsby C’est Moi

In the media frenzy generated by Baz Luhrman’s film, you hear a lot about Gatsby but not so much about Fitzgerald. He’s the forgotten man, overshadowed by his own creation. Gatsby lives, while his creator, the poet laureate of Old Nassau, is a tragic phantom. Online, on network and cable television, even on political talk shows like Chris Mathews’s Hardball, the charismatic Gatsby is front and center along with the Great Baz and a lot of chatter about poor boys, rich girls, and the American dream. Meanwhile Fitzgerald seems to be hanging on to his creation’s coattails. It’s almost as if Gatsby wrote Gatsby, and actually, that’s what I’ve been talking about: Fitzgerald and Gatsby are one; in Fitzgerald’s variation on Flaubert’s “Madame Bovary c’est moi,” the dreamer becomes his dream. Fitzgerald says as much in a letter to a friend written a few months after the novel appeared: “you are right about Gatsby being blurred and patchy. I never at any one time saw him clear … for he started out as one man I knew and then changed into myself.” Edith Wharton picks up on the connection when she says “how much I like Gatsby, or rather His Book” in a letter thanking Fitzgerald for sending her a copy.

A Radiant World

The first time Fitzgerald gives Maxwell Perkins a hint of what he’s up to with the book that became The Great Gatsby, he draws a line between it and his two previous novels and the “trashy imaginings” in his stories: this is “purely creative work … the sustained imagination of a sincere yet radiant world.” For that reason, it will be “a consciously artistic achievement and must depend on that as the first books did not.” In a brief letter to a magazine editor in April 1924, he describes his work in progress as [italics added] “a new thinking out of the idea of illusion (an idea which I suppose will dominate my more serious stuff) …. The business of creating illusion is much more to my taste and talent.” Gatsby could have been thinking along the same lines when he began amassing the fortune that would enable him to imagine he could create an illusion fascinating enough to capture Daisy. In August of the same year, in a letter to a rich friend, Fitzgerald is using similar language as he contemplates the story’s inevitable confrontation with the death of the dream: “the whole burden of this novel” is “the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world so that you don’t care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory.”

It’s finally pointless to say, as has been said of Baz Luhrman’s attempt, that Gatsby is “unfilmable” when it’s been filmed five times and will go on being filmed indefinitely. It seems clear by now, however, that no filmmaker can truly, in the Jamesian sense, do Gatsby.

———

Francis Cugat’s cover painting, Celestial Eyes, is owned by the Princeton University Library. With all the attention that’s being lavished on this latest and most lavish Gatsby, now might be a good time to display the work that inspired one of the novel’s most significant images.