Reading Brooklyn Without a Map, or Henry Miller Saves the Day

By Stuart Mitchner

The largest and most unknown continent of all is Brooklyn. You can say that I’ve gone out into the wilderness five hundred times armed with a trusty map, now worn to tatters, and have prowled about, exploring the place in the dark hours of the night as not even Stanley explored Africa in his search for Dr Livingstone.

—Thomas Wolfe (1900-1938)

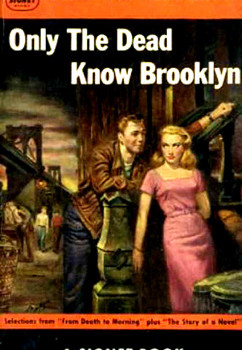

It can also be said that the man with the map — a writer of immense, notoriously verbose novels — summed up the story of his writing life in a six-page monologue about someone attempting to do the impossible. The situation described in Thomas Wolfe’s letter of December 11, 1933, from 5 Montague Terrace in Brooklyn Heights, is the subject of “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn” (1935), a story told in a Brooklynese dialect in which the 6’6 Wolfe is the “big guy” with the map asking a Brooklynite how to get to Eighteenth Avenue and Sixty-second Street. In the letter, the prosaic statement, “The Brooklyn people boast that you can live here a lifetime and never get to know their town,” becomes the story’s punchline, “It’d take a guy a lifetime to know Brooklyn t’roo an’ t’roo. An’ even den, yuh wouldn’t know it all.”

Williamsburg Surprise

Brooklyn’s on my mind after three hours wandering around Williamsburg while my son attacked acres of used LPs in the Academy Records warehouse on North 6th Street. I’ve never looked forward to these Brooklyn visits, thanks to past misadventures driving across the Williamsburg Bridge. Not even the knowledge that the saxophone colossus Sonny Rollins used the bridge’s walkway as a practice space during his sabbatical in 1959-61 could soften the blow of being shunted onto the vehicular Russian Roulette of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway or airhorn-blasted into a near-fatal panic by a tailgating truck.

What a difference a book makes. Take my copy of the 1938 Obelisk Press/Paris edition of Henry Miller’s Black Spring, the pages yellowed and brittle and drenched with atmosphere, as much a place as a book, the opening chapter, “The 14th Ward,” bearing an in-your-face epigraph, “What is not in the open street is false, derived, that is to say, literature.” It’s Henry Miller all the way, still feeling the creative headwind that produced the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, he’s asking no questions, he’s got no map in his hand, he’s grabbing your arm, you can almost hear his Brooklyn accent, “I am a patriot — of the 14th Ward, where I was raised. The rest of the country doesn’t exist for me, except as an idea, or history, or literature.”

So why am I excited? Why has Williamsburg suddenly become a desirable destination in spite of the dreaded crossing? Because just around the corner from Academy Records is the house Henry Miller grew up in. I’m in the 14th Ward. Whatever they may call it these days, it’s his ward. No longer do I have to kill three hours in a place without a single inspirational association. I knew Miller had lived in Brooklyn, I’ve heard recordings, he may not be as extreme with his “t’roo and t’roos” as the character in Wolfe’s story, but you know where he’s coming from. I’d always assumed he grew up in one of those far-flung spots on Wolfe’s tattered map, like Bushwick, Myrtle Avenue, or the street where 13-year-old Henry’s life was changed one day when a book peddler sold him what he thought was a cops-and-robbers penny dreadful called Crime and Punishment by some Russian writer with an unpronounceable last name. In Black Spring, “It was exactly five minutes past seven, at the corner of Broadway and Kosciusko Street, when Dostoievski first flashed across my horizon.”

As soon as I dropped my son off at Academy, I walked a few short blocks and found myself face to face with Henry Miller’s boyhood home, which is still standing at 662 Driggs Avenue, a modest three-story red-brick building with a whole block to itself. My guess is Miller would be glad to know that no historical marker has been hammered in place next to the painted-over shop windows on the ground floor. Here it is, as he writes in Black Spring, “The house wherein I passed the most important years of my life.”

Miller’s house made my day. Out of the labyrinth of streets that fascinated and challenged and submerged Thomas Wolfe, here’s the place where Miller, “born and raised in the street,” began living the book of his life: “To be born in the street means to wander all your life, to be free. It means accident and incident, drama and movement. It means above all dream.” And across the way, still there, is the “ideal street,” Filmore Place, described in Tropic of Capricorn: “Ideal for a boy, a lover, a maniac, a drunkard, a crook, a lecher, a thug, an astronomer, a musician, a poet, a tailor, a shoemaker, a politician.”

Perhaps it all comes down to attitude. In his own way, Miller, like Wolfe, attempted the impossible, but he never asked for directions. He found his voice in an attitude of joyous rhetorical arrogance of which Brooklyn native/resident Norman Mailer writes, “one has to take English back to Marlowe and Shakespeare before encountering a wealth of imagery equal in intensity.” Though Wolfe was a gifted mimic, as in “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn,” he didn’t live long enough to throw the map away and stand outside himself. William Faulkner’s oft-quoted rationale for ranking Wolfe at the top of his list of writers (he isn’t even on most lists in 2013) concerned the magnitude of the attempt — “his was the most splendid failure. He had tried hardest to take all the experience that he was capable of observing and imagining and put it down in one book, on the head of a pin.”

Working in Brooklyn

Thomas Wolfe was my heroic, word-drunk alter ego the summer I was writing my first novel and riding the 4th Avenue Local from 8th and Broadway in Manhattan into darkest Bay Ridge to work in the office of a hiring hall on the Bush Terminal docks. The best thing about the job was getting to say, at age 18, “Waterfront, Mitchner” every time I picked up the phone. On my way back to the subway each afternoon I had to run the gauntlet of stares and occasional taunts from tough-looking teenagers, male and female, hanging out on stoops (picture the ones in Bruce Davidson’s Brooklyn Gang: Summer 1959). I must have looked like an alien species, a hick from the sticks; at work I was greeted with friendly obscenities (here comes that “blankety-blank Hoo-sher so-and-so”) and kidded mercilessly about the fat love letters from my “little Hoo-sher sweetheart” that I arrived with every morning and read on coffee breaks. Among my co-workers was a sadistic, foul-mouthed ex-cop who delighted in tormenting the other non-Brooklynite, a timid Danish-American in his fifties who lived in a cheap hotel in lower Manhattan and rode the subway home with me every day miserably bemoaning his lot because of the way the ex-cop and the other people in the office harrassed him.

Crane’s Bridge

Two summers later when my first novel was published, complete with Wolfian cliches (“The rivers flowed”), I was staying on the top floor of a friend’s State Street brownstone in “dah Heights.” On hot summer evenings we would walk to the Promenade to admire the view of the towers of lower Manhattan, passing on the way Wolfe’s Montague Terrace residence (W.H. Auden lived in the same block five years later). Another Heights resident, poet Hart Crane, described the effect of the view soon after moving into the “quiet and charming” neighborhood in 1924: “It is particularly fine to feel the greatest city in the world from enough distance, as I do here, to see its larger proportions.” In another letter, he speaks of living “in the shadow” of the subject of his most famous poem, “The Bridge” (“It was in the evening darkness of its shadow that I started the last part of that poem”). Crane called the Brooklyn Bridge not only “the most beautiful in the world” but “the most superb piece of construction.” He didn’t know at the time that he was writing his poem in the room once inhabited by the bridge’s designer, Washington Roebling.

Whitman Opens His Arms

In the summer of 1878, some 50 years before Crane moved into the house on Columbia Heights, Brooklyn’s single most compelling literary figure was gazing beyond “the grand obelisk-like towers” of the then-unfinished bridge to “the grandest physical habitat and surroundings of land and water the globe affords — namely, Manhattan island and Brooklyn, which the future shall join in one city.”

While Wolfe made a subject of the impossibility of fathoming Brooklyn, Walt Whitman simply opened his arms and took it all in and all America with it, writing in the preamble to his first self-published song of himself, “Without effort and without exposing in the least how it is done the greatest poet brings the spirit of any or all events and passions and scenes and persons some more and some less to bear on your individual character as you hear or read. To do this well is to compete with the laws that pursue and follow time.”

Turn back to the title page and all you see is Leaves of Grass in massive letters and under it no publisher, no author, only this boldly printed evidence of time and place:

Brooklyn, New York: 1855.

On the facing page there he is, the sparsely bearded poet, sketched in an attitude of no-nonsense intensity, eyeing you, daring you to take the plunge, one hand in the pocket of his corduroy trousers, other arm bent, shirt open at the throat, dark undershirt showing at the top, hat at an angle, worn by a man who contains multitudes.