Sneaking Through Baltimore With Lincoln, Pinkerton, and America’s First Female Private Eye

By Stuart Mitchner

He reached the Capital as the poor, hunted fugitive slave reaches the North, in disguise, seeking concealment, evading pursuers … crawling and dodging under the sable wing of night. He changed his programme, took another route, started at another hour, travelled in other company, and arrived at another time in Washington. We have no censure for the President at this point. He only did what braver men have done.

—Frederick Douglass,

Life and Times (1881)

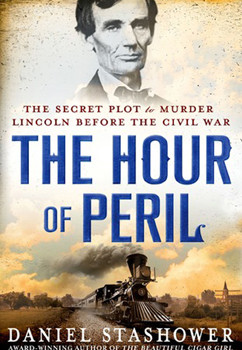

There are many reasons to think well of Baltimore, in spite of its being the place where the plot to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln was hatched and might have been carried out but for the counter machinations described in Daniel Stashower’s The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (Minotaur Books $26.99).

Let’s start with the fact that the Baltimore Ravens are the only professional sports team in the world named for a poem. When the owner of the Cleveland Browns decided to move his NFL franchise to Baltimore, a telephone survey and a fan contest came up with a list of 17 names that was trimmed to three by focus groups of 200 Baltimore area residents and a phone survey of 1000 people. A fan contest drawing 33, 288 voters picked Edgar Allan Poe’s immortal bird over the Marauders and the Americans.

It’s hard not to like a city that chooses for its team’s mascot and emblem a bird of ill-omen from a poem dreamed up by a dissolute genius who died under suspect circumstances on that same city’s mean streets. And how have these Ravens fared under the curse of Poe’s “grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore”? A year after taking the field in 1999, they won the Super Bowl. Last year Edgar’s team did it again. All told, since they moved to Baltimore and became the Ravens, they have made the play-offs nine times.

Other reasons to hang four big stars on Baltimore: the Florentine tower once crowned by a giant bottle of Bromo Seltzer; the red neon of the Domino sugar sign reflected in the harbor; the Fells Point diner immortalized in Barry Levinson’s Diner, and, of course, Camden Yards, a throwback to baseball’s glory years built on a site associated with the proposed assassination of the man who saved the Union. Meanwhile let’s add a fifth star for David Simon’s peerless five-part portrait of “Bulletmore Murderland” in The Wire, and Randy Newman’s “Baltimore,” arguably the best song ever written about an American city. Whether or not it’s true that Newman composed it without ever having actually experienced the place, the way he sings the bluesy lament over an edgy, atmospheric piano vamp (“It’s hard just to live”), you know he owns Baltimore the way Ray Davies owns Waterloo Station and Wordsworth owns Westminster Bridge and Keats owns the Grecian Urn.

Travel back to February 1861 in The Hour of Peril and the city’s not something you want to write a song about, it’s the “mob-town” of secessionist riot, bristling with weaponry, like a malevolent juggernaut set in motion to crush the new president before he can reach the nation’s capitol. In Stashower’s book, Baltimore is the epicenter of villainy, a haven for radicals such as Poe’s eerie double, the assassin-in-waiting John Wilkes Booth, who, like Poe, is buried in Baltimore. Stashower’s compulsive page-turner becomes a litany of threats until the sheer magnitude of the communal death-wish expressed in vows to shoot, stab, bludgeon, or bomb the despised “tyrant” makes The Hour of Peril seem nothing less than a prologue to the moment Booth fired the shot heard round the land on April 14, 1865.

And in case you think everyone in Baltimore has come round to agreeing with the rest of the country that Lincoln was our greatest president (per Nate Silver’s composite FiveThirtyEight poll on nytimes.com), you need only look up the assassin on welcometobaltimorehon.com, to find, from March of this year, “a gaint [sic] who killed a midget god bless john wilkes booth,” and from September 2012, “God Bless the Great Maryland Hero.”

“All Was Confusion”

Apparently there are people who still contend that Baltimore posed no serious threat to Lincoln’s life, that he could have moved from Calvert Street Station to Camden Depot as scheduled. At the time, security constraints precluded disclosure of the evidence that might have silenced those who were lambasting him for not riding proudly into town to make a speech like the ones he’d been delivering to cheering crowds on his triumphant post-election whistlestop tour from Springfield, Illinois through Indiana, Ohio, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

Besides being a compelling narrative, The Hour of Peril makes a strong, thoroughly researched case for the life-saving necessity of presidential subterfuge on February 22-23, 1861. No one but the most blindly biased reader will finish the book believing that Lincoln could have passed through Baltimore unscathed. The Pratt Street riot that occurred two months later and cost the lives of four Union soldiers and 12 civilians (historians consider it the first bloodshed of the Civil War) offers a hint of the calamity prevented by Alan Pinkerton’s detective work, among numerous other factors that convinced the president-elect to let discretion be the better part of valor. And, as Lincoln feared, the decision to sneak through Baltimore incognito in a different train hours ahead of schedule (arriving in Washington, as he put it himself, “like a thief in the night”) exposed him to ridicule from newspapers both north and south.

In fact, even friendly crowds proved to be dangerous. There were crushes at every station, near-riots, injuries, drunken brawls, squads of police “swept aside,” soldiers called in to maintain order. In Albany, “all was confusion, hurry, disorder, mud, riot, and discomfort.” In New York City, where the security and crowd control were impressively managed, there was still “much anxiety,” according to the poet Walt Whitman, who “had no doubt” that “many an assassin’s knife and pistol lurk’d in hip or breast pocket.” It was worse in New Jersey, which Lincoln had failed to carry in the election and “where signs of ambivalence, if not outright hostility, were plainly visible along the route.” In Newark, Lincoln’s carriage “passed a black-bearded effigy swinging by the neck from a lamp post.”

Lincoln’s Character

Stashower’s account of Lincoln’s words and actions during the 13-day tour provides some unusual glimpses of the man, some less than flattering, but all in the arc of his character as history and legend have shaped it — unaffected, down to earth, fond of a quip or a good story, cool under fire. But then his virtues were also seen as defects. Old Abe the country wit was no more than a bumptious fool with delusions of grandeur to his enemies, and even his friends thought some of the speeches he made along the way weak and foolishly out of touch with the plight of the nation.

The Movie

The Baltimore Plot inspired Anthony Mann’s 1951 film, The Tall Target, as exciting a train movie as Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. Dick Powell stars as John Kennedy, a New York City police detective named after the real-life New York police commissioner who vied with Pinkerton for the credit in warning Lincoln away from Baltimore. While the narrative excitement in The Hour of Peril develops out of the struggle to ensure Lincoln’s safe passage to Washington, The Tall Target takes the term “action-packed” to another level. Along with Paul Vogel’s richly film-noirish cinematography, the fun of the movie is in the way the life-and-death struggle meshes with details of the mid-19th-century train, the curtained berths, the engineers and firemen, the horse-drawn passage of the carriages through the streets of Baltimore, the interplay of passengers unaware of the high-stakes battle going on around them (one such scene takes place at the New Brunswick station). Powell/Kennedy’s life is inadvertently saved by one of his enemies, a conspirator (played by the ever-effervescent Adolphe Menjou), and then by a conflicted black servant (a sweetly sympathetic Ruby Dee) who has a warm quasi sibling relationship with her mistress (Paula Raymond). Judging from the number of times Powell is either hanging by one hand from the moving train or crawling along on top of it or chasing after it, his performance must have been the most exhausting of his Hollywood career.

The Captivating Widow

At the end of The Tall Target the female Pinkerton agent who discreetly boards the train in Baltimore with the disguised president-elect is played by an actress with a name (Katherine Warren) almost identical with that of her real-life counterpart Kate Warne. Quoted in The Hour of Peril, Pinkerton depicts the first female detective in America as a “slender, graceful … perfectly self-possessed” young widow with “captivating blue eyes — sharp, decisive, and filled with fire.” Half a century ahead of her time (the NYPD’s first female investigator was hired in 1903), she proved to be “a versatile and utterly fearless operator,” as when she forged “a useful intimacy” with the wife of a suspected murderer and posed as a fortune teller (“the only living descendant of Hermes”) in the investigation of a superstitious suspect. Her role in the uncovering of the Baltimore plot was essential. She infiltrated Baltimore society as a “Mrs. Barley of Alabama” with “an ease of manner that was,” in Pinkerton’s words, again, “quite captivating” as she cultivated “the acquaintance of the wives and daughters of the conspirators.” While standing up to male operatives and others trying to bully classified information out of her, Mrs. Warne successfully delivered the messages that helped convince Lincoln to go along with Pinkerton’s plan and board an earlier train in the guise of her invalid brother for the last perilous stretch of the journey to Washington; it was also up to her to make sure they had berths in the rearmost part of the car. Mrs. Warne recalled that the president was “so very tall that he could not lay straight in his berth” and that he “talked very friendly for some time …. The excitement seemed to keep us all awake.”

Pinkerton’s habit of using the word “captivating” in regard to Kate Warne has tempted some to wonder if they had a relationship outside the profession (at 42, he was almost 20 years her senior). Perhaps someone will remake The Tall Target with a romantic subplot in which the Dick Powell character’s accomplice is a mysterious female who appears at crucial moments and by the end has everyone, including Abraham Lincoln, under her spell. Randy Newman could compose a soundtrack worthy of her -— and Baltimore.