On the Money: Front Page Fun With Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Kelly Clarkson

By Stuart Mitchner

What’s not to like when two giants of English literature are making news in the 21st century? What’s not to like about seeing a portion of Shakespeare’s handwriting on the front page of the New York Times and Jane Austen’s face peering out from the 10 pound note the Bank of England will put into circulation in 2016?

Shakespeare made page one of the Times last week (“Much Ado About Who: Is It Really Shakespeare”) because a scholar in Texas has claimed that the Bard is responsible for 325 lines among the “additional passages” included in the 1602 quarto edition of Thomas Kyd’s play, The Spanish Tragedy. This claim has some residual merit, if only because Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Charles Lamb noted the possibility in 1833. It does seem odd that it’s taken 180 years before the news was deemed fit to print. Not that I don’t enjoy seeing Shakespeare’s name first thing in the morning in bigger type than Christie’s or Weiner’s or Bloomberg’s.

This was not the only time Shakespeare finds have been front-page news. In January 14, 1996, a professor at Vassar was toasted for having proven through computer analysis that a hitherto anonymous 578-line elegy was by Shakespeare. Six years later, when the dust of the ensuing debate cleared, the professor made news again by recanting his claim after overwhelming evidence showed that the elegy was by Shakespeare’s contemporary, John Ford.

Another bogus news flash in the name of the Bard lit up page one of the November 24, 1985 New York Times, to tell the world that Gary Taylor, a “32-year-old American from Topeka, Kan. has discovered a previously unknown nine-stanza love lyric” that “appears to be the first addition to the Shakespeare canon since the 17th century.”

An addition to the canon sounds exciting until you read the lyric in question, a piece of borderline doggerel that begins “Shall I die? Shall I fly” and features gems like “Suspicious doubt, O keep out” and “’Twere abuse to accuse,” “Fairest neck, no speck,” and “For I find to my mind pleasures scanty.” Besides being occasionally incoherent, it’s teeming with cliches like love/dove, fair brow, love’s prize, “gentle wind did sport” and so on and on.

Worse yet, the man from Topeka was allowed to include this embarrassment, this insult to Shakespeare, in the edition of the Works he was co-editing (don’t ask why or how). The only person quoted backing Taylor’s claim in the Times’ jump-the-gun story (“It looks bloody good to me”) was one John Pilcher of St. John’s College, whose position there is unstated, and no wonder. Meanwhile Taylor managed to insult yet another genius in the process of admitting that “while it’s not Hamlet,” it’s “a kind of virtuoso piece, a kind of early Mozart piece.” Taylor’s Wikipedia entry admits that his claim “has since been almost universally rejected.” Undaunted, unbowed, unashamed, the Florida State University professor is the author or editor of four of the volumes included on the Random House list of the 100 most important books on Shakespeare. In 2010, Oxford University Press named him the lead editor of The New Oxford Shakespeare, to be published in 2016, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. The mind reels at the thought of what may be done in the course of, in Taylor’s words, “determining what Shakespeare wrote” in the ensuing “enormous, international frenzy of historical research.”

As Fats Waller liked to say, “One never knows, do one?”

It would take Terry Southern come back from the dead to do black-comedy justice to the tale of two sixties-styled Americans, one from Texas with shoulder-length hair, in 2013, and one from Kansas with an earring in his ear, in 1985, who managed to parlay themselves into page one prominence as Shakespeare heavyweights. It could be really funny, painfully funny.

The Ring

So what’s not to like about putting Jane Austen on the ten pound note? Don’t ask Mark Twain whose admission in a letter from 1898 — “Every time I read Pride and Prejudice, I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone” — would delight some of the bloggers who attacked Austen after the Bank of England broke the news. Never mind the shin-bone: two women who lobbied for Jane have been threatened with bombing, burning, pistol-whipping, and rape.

On a brighter note, there’s the saga of the Ring, not the Wagner Ring nor the Tolkien Ring but the turquoise and gold ring once worn by Austen and recently purchased at auction for £152,450 (about $230,000) by Texas-born pop singer Kelly Clarkson, whose worldwide hit single, “My Life Would Suck Without You” holds the record for the biggest leap to number one in the history of the Billboard Hot 100 Chart. Perhaps the most famous member of the American wing of the Jane Austen Appreciation Society, Clarkson seemed to take it in stride when the government refused to let the ring leave the country. If you want to read some generally amusing back and forth on the issue, visit the Guardian blog (“Jane Austen Ring: would its sale to Kelly Clarkson be a loss to the nation?”), where Clarkson comes out on top in a poll (the “no”s have it, 65 to 35 percent) and the target of choice is the Tory government.

I don’t have a problem with the surfacing of Jane Austen in the regions of pop culture graced by Kelly Clarkson. In fact, the Jane Austen people busy raising money to buy back the ring see only good things for their cause in the pop star’s devotion.

What would Jane Austen make of her ebullient American fan? An impossible question, of course, but my guess is that she wouldn’t take long to warm to Clarkson, and that in spite of the title, she might actually tolerate “My Life Would Suck Without You,” with all its joyous emotional energy. More to the Pride and Prejudice point, how could she resist the singer’s latest, a jaunty, jumping wedding number called “Tie the Knot”?

While Austen would no doubt need another internet crash course to travel through time from John Dowland’s “Weep No More Sad Fountains” to Schubert to the Beatles to an appreciation of Clarkson, music is very much “the food of love” when Elizabeth Bennet’s singing and playing and dancing help put things in perspective with Mr. Darcy. Earlier in the narrative, during a gathering at which Darcy is present, Elizabeth experiences “the mortification” of seeing her younger sister Mary, “after very little entreaty, preparing to oblige the company” with a song. After unsuccessfully attempting to discourage Mary with “significant looks” and “silent entreaties,” Elizabeth suffers through the performance with “the most painful sensations” and “an impatience which was very ill rewarded” when Mary is asked to sing another song and happily does so. The problem for Elizabeth is that “Mary’s powers were by no means fitted for such a display; her voice was weak, and her manner affected.”

Whether she’s singing “My Country Tis of Thee” at President Obama’s second inaugural or making the most of the cliched love-is-a-battlefield lyrics of “My Life Would Suck,” Kelly Clarkson’s considerable powers are definitely fitted for such displays.

A Delightful Creature

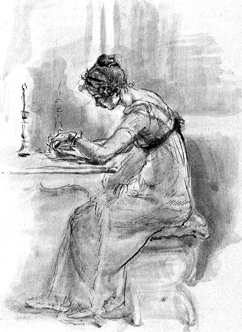

Published 200 years ago, in January 1813, Pride and Prejudice was Jane Austen’s “own darling child,” as she told her sister Cassandra. In the same letter, she called Elizabeth Bennet “as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print” and wondered how she “would be able to tolerate those who do not like her at least.” With those words, it’s as if the author were introducing one of her favorite characters into the society of the ages, where she will be liked and loved even into the 21st century, on the page and on the screen — and on the Jane Austen ten pound note, where you can see Elizabeth in the background above an image of Godmersham Park, home of Jane’s brother, Edward Austen Knight. She’s at her writing desk, an image that also suggests the author at work. The drawing, pen and black ink, gray wash, over pencil, is by the American artist Isabel Bishop (1902-1988), from the edition of Pride and Prejudice (E.P. Dutton 1976) that features 20 illustrations of the 31 she contributed, all of which are now at the Morgan Library and Museum. It’s impossible to regard Bishop’s depictions of the novel’s female characters without thinking of the girl friends, shop girls, and working women she drew and painted for the better part of 50 years in her Union Square studio.

To know Isabel Bishop was to sometimes feel that you were in a novel that, depending on the occasion, could have been imagined by Jane Austen, or George Eliot, or Henry James, or Edith Wharton. Isabel would have been amused to find that the Bank of England had put her image of Elizabeth Bennet on the ten pound note. What would Jane Austen think? Writing to her brother Frank in September 1813 when Pride and Prejudice was being read and wondered over, she observes “that the Secret [of her authorship] has spread so far as to be scarcely the Shadow of a secret now …. I shall not even attempt to tell Lies about it — I shall rather try to make all the Money than all the Mystery I can of it — People shall pay for their knowledge if I can make them.”

As for Shakespeare’s standing with the Bank of England, he’s got nothing to complain about. From 1970 to 1993 his was the face on the 20 pound note.