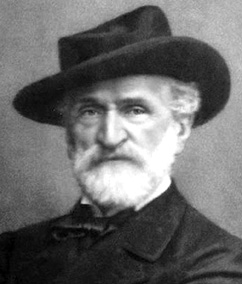

Beyond the Social Masquerade on Verdi’s 200th Birthday

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Before I plunge into a column on Giuseppi Verdi, whose 200th birthday was last Wednesday, I have to admit that it’s taken me an embarrassingly long time to come to my senses about opera. A random search on YouTube just now brought me to the Guardian music blog’s birthday celebration in which aficionados were asked to send a clip of their favorite Verdi moment. At the top of the list was a black and white video of Maria Callas as Violetta in a 1958 Lisbon production of Verdi’s La Traviata said to be “precious beyond price” because it’s the only surviving film of Callas “in a role she made her own.” The opening image of people in period dress — a party scene where no one looks comfortable, everything posed, stagey, static — shows that what made it hard for me to get into opera at a time when I was able to appreciate other forms of classical music was that it seemed to take itself so seriously — so much that it made you want to see Groucho and Harpo and Chico set loose on the scene, as M-G-M did so devastatingly in A Night at the Opera.

Opera suggests life on the grand scale. The first opera I ever saw, at 19, was a production of Puccini’s Turandot at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, where the scale was so grand that it got in the way of the music. Rome overwhelmed it. And the surroundings! I mean, Orson Welles was sitting five rows in front of me. My parents bought me an LP of the highlights for my birthday, but all I wanted to hear after that first summer in Europe were songs like “Nel blu dipinto di blu.”

The way Dominic Modugno’s “Volare” swept Europe that summer, on the street, in the air, everywhere, was a throwback to what happened the day after a new opera by Verdi (1813-1901) was performed, when his songs could be heard sung and played on the street by singers, bands, and organ grinders. Verdi was composing the equivalent of hits a century before “Volare.” Of course one of the stereotypes of Italy is that people of all social classes are mad for opera. One of my most memorable hitchhiking experiences was a ride to Naples with a neatly dressed man (suit and tie, expensive-looking footwear) who turned out to be an insurance salesman, and before you could say “Giuseppi Verdi” he was singing “Libiamo, libiamo” from La Traviata and singing it, to my untrained ear, magnificently. Having just seen Placido Domingo sing it in Franco Zefferelli’s spectacular 1982 film of that opera, I have no doubt that was the song — how could I forget? We were on the Amalfi Drive, winding around cliff edge curves, the singing salesman steering with one hand while lofting an invisible goblet with the other.

Setting It in Motion

Zefferelli’s La Traviata presents sensations no opera house in the world could create. After the rich dark depths of the funereal opening, in which Violetta (Teresa Stratas), the “strayed woman” of the title, seems to come back from the dead, Zefferalli sets everything in motion. No one’s standing around looking pompous or posed or static, the party’s in a whirl, the very lamps and candelabras seem to sing and shine and glow like gold. The camera makes music of movement, sweeping you here and there but always smoothly, always true to and in synch with the melodic contours of the sequence. What Zefferelli does with the great party and masquerade scenes in La Traviata was so intoxicating (sheer ecstasy of imagery, no wasted spaces, nothing left to mundane chance, every detail at once subtle and vivid, as if the very molecules had been painted with light) that I didn’t fully appreciate Teresa Stratas’s charming, passionate, down to earth Violetta. Slightly built, with a very expressive Greek face, which becomes irresistible whenever Zefferelli brings the camera into kissing range, Stratas is like one of the great courtesans from Balzac’s Lost Illusions come to life. There’s no way not to love this woman when she’s singing full out and feeling every note. And when the doomed beauty lets go and scampers wildly about that incredible interior — a fantasy of elegance even Balzac would be hard put to describe — singing of ecstasy, madness, freedom, and euphoria, “love a heartbeat through the universe,” she has you believing it.

The Social Masquerade

The experience of reading Frank Walker’s 1962 biography of Verdi has in common with Stratas and Zefferelli’s Traviata the shining central presence of a charming, intelligent, articulate woman, Giuseppina Strepponi, an acclaimed soprano in her time who came to Verdi with a shady reputation not unlike Violetta’s. The most interesting portions of Walker’s book are built around long letters from Strepponi, Verdi’s second wife, who called herself “your Nuisance” and “Peppina” and called him “my Pasticcio.” Their relationship began in 1847 and continued until her death in 1897. Her letters are full of fancy and feeling, warmth and wit (an entire chapter is titled “Giuseppiana at her Writing Desk”). In one, she expresses her less than positive feelings about Verdi’s hometown Bussetto (“And to think that that lofty soul of yours came spontaneously to lodge in the body of a Bussetano”) and prefers to imagine that “an exchange took place in your childhood and that you came into existence as the result of some sweet lapse of two unhappy and superior beings.” She goes on to a statement that seems to reflect the milieu of La Traviata: “We are still the whole world to each other and watch with high compassion all the human puppets rushing about, climbing up, slipping down, fighting, hiding, reappearing — all to try to put themselves at the head or among the first few places, of the social masquerade.”

In another letter, after referring to the esteemed Verdi who “goes to pay calls on ministers of state and ambassadors,” she writes that “many times I am quite surprised that you know anything about music! However divine that art and however worthy your genius of the art you profess, yet the talisman that fascinates me and that I adore in you is your character, your heart, your indulgence for the mistakes of others while you are so severe with yourself, your charity, full of modesty and mystery, your proud independence, and your boyish simplicity — qualities proper to that nature of yours, which has been able to preserve a primal virginity of ideas and sentiments in the midst of the human cloaca!”

“Let’s Do ‘Falstaff’”

Decades later when Verdi was approaching 80, the opera legend Adelina Patti observed that “he only looks sixty … jolly and gay as a lad.” Obviously Patti was picking up on the spirited overflow from the composition of Falstaff, which Verdi came to refer to as “The Big Belly” and began when he was 79. “What a joy!” he wrote to Boito, his liberettist. “To be able to say to the Audience: ‘We are here again! Come and see us!’ So be it. Let’s do Falstaff! Let’s not think of obstacles, of age, of illness!” The zany pacing and rhythms of the score are reflected in the madcap style Verdi gives to his accounts of it: “The Big Belly is on the road to madness. There are some days when he does not move, he sleeps, and is in bad humor; at other times he shouts, runs, jumps, and tears the place apart. I let him act up a bit, but if he goes on like this I will put him in a muzzle and a straitjacket.”

Falstaff was a triumph. The ovation at La Scala lasted a half hour. Boito said “All the Milanese are becoming citizens of Windsor [the opera was based primarily on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor].” When it was over, Verdi celebrated it in the same terms: “Everything ends! Alas, alas! too soon! The thought is too sad! It’s all Big Belly’s fault. What madness! Everyone … everything on earth is a joke!”

Verdi died at the age of 88 on January 27, 1891. At the funeral service in Milan, Toscanini conducted orchestras and choirs composed of musicians from throughout Italy. To date, it is said to have been the largest public assembly of any event in the history of Italy, with a crowd of 200,000.

Besides Frank Walker’s Verdi the Man (Knopf 1962), I consulted Mary Jane Philips-Martz’s Verdi: A Biography (Oxford 1995). Zefferelli’s films of Verdi’s La Traviata and Otello are available on DVD at the Princeton Public Library.