“Woman As She Is”: Robert Louis Stevenson and His American Wife

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Born on this day, November 13, 1850, in Edinburgh, Robert Louis Stevenson was writing The Weir of Hermiston when he died of a cerebral hemorrhage on December 3, 1894, in Samoa. He dedicated the unfinished novel to his wife Fanny:

Take thou the writing: thine it is. For who

Burnished the sword, blew on the drowsy coal,

Held still the target higher, chary of praise

And prodigal of counsel — who but thou?

So now, in the end, if this the least be good,

If any deed be done, if any fire

Burn in the imperfect page, the praise be thine.

Although Stevenson considered his marriage “the best move I ever made in my life,” he described Fanny, in a letter to J.M. Barrie written the year before he died, as “a violent friend, a brimstone enemy.”

“Damn Queer”

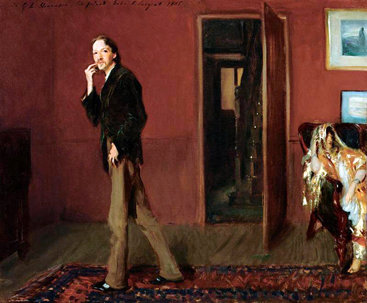

Painted at Bournemouth in the summer of 1885, John Singer Sargent’s portrait, Robert Louis Stevenson and his Wife, which was on loan to the Princeton Art Museum some years ago, has to be one of the strangest images Sargent ever put on canvas. For one thing, Mrs. Stevenson is seated off to the side, at first glance barely distinguishable from the decor, so much so that she draws attention to herself by almost not being there. This frame from a home movie on pause may say more than the painter intended about the couple’s relationship, though Sargent seemed in amused agreement when Fanny observed, “I am but a cipher under the shadow.” Stevenson looks too thin to cast more than a sliver of shadow. He’s wandering away from his wife, not deliberately, but as if he were following the course of a stray thought. In his own account, he judged the painting “excellent” but “damn queer as a whole” and “too eccentric to be exhibited. I am at one extreme corner; my wife in this wild dress, and looking like a ghost, is at the extreme other end.” Draped in a colorful Indian fabric, with one bare foot just peeping through, Fanny resembles not so much a ghost as a spaced-out gypsy dancing girl cooling her heels. The portrait may be to blame for the rumor that Mrs. Stevenson showed up barefoot at London dinner parties.

Books Without Women

In an essay in the April 1888 Century Magazine, Henry James, who was a frequent guest when the Stevensons were living in Bournemouth, points out that Stevenson “achieves his best effects” in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde “without the aid of the ladies …. It is usually supposed that a truly poignant impression cannot be made without them, but in the drama of Mr. Hyde’s fatal ascendancy they remain altogether in the wing.”

It’s no surprise that the author of The Portrait of a Lady and creator of numerous memorable female characters would be sensitive to their absence in Stevenson, as he noted at the outset of the same essay. After describing the “gallantry” of Stevenson’s style (“as if language were a pretty woman” and the author “something of a Don Juan”), James goes on to observe that “it is rather odd that a striking feature” of Stevenson’s gallant nature is “an absence of care for things feminine. His books are for the most part books without women, and it is not women who fall most in love with them.” James surmises that “It all comes back to his sympathy with the juvenile, and that feeling about life which leads him to regard women as so many superfluous girls in a boy’s game …. Why should a person marry, when he might be swinging a cutlass or looking for a buried treasure? Why should he go to the altar when he might be polishing his prose?”

In “real life” and real time (1880), Stevenson pursued Fanny all the way to California with the fervor of a cutlass-wielding, treasure-hunting action hero, risking everything, health, funds, work, parental disfavor, crossing an ocean and a continent to track her down and win her hand, though doing so meant taking responsibility for three children from her previous marriage.

Contrary to the situation pictured by Sargent, Fanny was an immensely formative force in Stevenson’s life. She was nearly as close to his work as he was, his first reader, his conscience, his antagonist. The writing he’s known and loved for, from Treasure Island on, was accomplished when she was by his side. How intimidating, then, to attempt to form a fictional woman when a very real and fearlessly judgmental one is peering over your shoulder. After reading the first draft of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Fanny was not only underwhelmed, she questioned the essence of his approach to the tale so heatedly that it led to “an almighty row,” after which, to Fanny’s horror, he threw the entire manuscript on the fire, having decided that she was right. The novel the world knows (or thinks it knows, given the liberties taken by various film versions) was written to address Fanny’s reservations about the first draft and in particular her insistence that he undertake to develop the “moral allegory” implicit in the situation.

In a letter to Henry James quoted in Claire Harman’s suggestively titled biography, Myself & the Other Fellow (2005), Stevenson describes the back and forth between husband/author and wife/critic, she “who is not without art: the art of extracting the gloom of the eclipse from sunshine.” He goes on to recount a recent falling out: “she tackled me savagely for being a canary-bird; I replied (bleatingly) protesting that there was no use in turning life into King Lear …. The beauty was we each thought the other quite unscathed at first. But we had dealt shrewd stabs.” No wonder Stevenson would call Fanny “the violent friend” and “brimstone enemy,” addressing her in letters as “Dear weird woman” and “my dear fellow.” In the same 1893 letter to J.M. Barrie he admitted, “She runs the show … handsome waxen face like Napoleon’s, insane black eyes, boy’s hands, tiny bare feet, a cigarette …. Hellish energy …. Is always either loathed or slavishly adored. The natives think her uncanny and the devils serve her. Dreams dreams, and sees visions.”

Maybe by now you’re thinking, as I am, “What a fantastic challenge such a character would be for any novelist.” Never mind James. Think Balzac or Dostoevsky or Proust.

From all accounts, Henry James knew Fanny better than did Stevenson’s other friends. He routinely added his “love” to her at the close of his letters, and the long letter he sent her after Stevenson’s death in December 1894 was warm and caring, yet he privately confessed to thinking her “a poor, barbarous and merely instinctive lady,” characterizing her to Owen Wister as “a strange California wife … if you like the gulch & the canyon, you will like her.” James’s invalid sister Alice compared her to “an organ grinder’s appendage” (her way of not saying “monkey”), with so large an ego that it “produced the strangest feeling of being in the presence of an unclothed being” (her way of not saying “naked”). Obviously, such comments say as much about James and his sister as they do about Fanny, but words like “barbarous,” the monkey reference, and Stevenson’s own use of “weird,” “insane,” “uncanny,” “devils,” “dreams,” “visions,” and “hellish energy” indicate qualities Mrs. Stevenson shares with Mr. Hyde. It was she, after all, who heard her husband’s scream and came to wake him when he was being consumed by the nightmare that inspired the transformation of Jekyll into Hyde.

Below Him

No less weird, uncanny, and barbarous is the P.S. that Stevenson appended to a letter praising Roderick Hudson, one of James’s lesser works. After prefacing the crude blow he’s about to strike as “a burst of the diabolic” (a Hyde-like note) he says, “I must break out with the news that I can’t bear The Portrait of a Lady …. I can’t stand your having written it; and I beg you will write no more of the like …. I can’t help it — it may be your favorite work, but in my eyes it’s BELOW YOU to write and me to read.”

This assault on a novel already being acknowledged as James’s masterpiece is wildly out of character. Perhaps Stevenson had had one drink too many. What was he thinking? What could have brought it on? More bewildered than hurt (“My dear Louis, I don’t think I follow you here — why does that work move you to such scorn?”), James knows better than to take it any further (“I feel as if it were almost gross to defend myself”). If nothing else, the outburst underscores the fundamental division James touched on when noting the “absence of care for things feminine” in Stevenson’s work, a point he comes back to decades later in his preface to the New York edition of The Portrait. Addressing the difficulty some novelists have with making a female character “the center of interest,” he observes that “even, in the main, so subtle a hand as that of R. L. Stevenson, has preferred to leave the task unattempted.”

Last Words

There’s no evidence that the female character at the heart of Stevenson’s last work, The Weir of Hermiston, was a considered response to James. If anything, making Christina Elliott “the center of interest” was a tribute to Fanny, as “the praise be thine” dedication implies. When the narrative breaks off in the ninth chapter, Christina is in emotional disarray, furious because the man she adores has come to her not to make love but “to trace out a line of conduct” for them “in a few cold, convincing sentences.” Her response is to subject him to “a savage cross-examination” that must have evoked smiles in readers familiar with the dynamic of Stevenson’s marriage, the “canary bird” meets King Lear.

The last passage Stevenson was ever to write, dictated to his stepdaughter the day he died, begins with a sentimental cliche with juvenile overtones (“He took the poor child in his arms”) — until “He felt her whole body shaken by the throes of distress, and had pity upon her beyond speech. Pity, and at the same time a bewildered fear of this explosive engine in his arms, whose works he did not understand, and yet had been tampering with. There arose from before him the curtains of boyhood, and he saw for the first time the ambiguous face of woman as she is. In vain he looked back over the interview; he saw not where he had offended. It seemed unprovoked, a wilful convulsion of brute nature ….”

And so everything ends with those two scarily resonant words.

It’s all there, as James would undoubtedly have recognized, from “the curtains of boyhood” to the “face of woman as she is.”