On James Agee’s Birthday: Celebrating New York Beginnings With Grace Kelly and Lou Reed

By Stuart Mitchner

New York City, how I love you, blink your eyes and I’ll be gone

just a little grain of sand.

—Lou Reed (1942-2013),

from “Nyc Man”

If anybody starts using me as scenery, I’ll return to New York.

—Grace Kelly (1929-1982)

Writing shortly after he’d moved to New York in August 1932, James Agee, who was born on November 27, 1909, describes listening at night to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on a phonograph in his office on the 50th floor of the Chrysler Building: “An empty skyscraper is just about an ideal place for it … with all New York about 600 feet below you, and with that swell ode, taking in the whole earth, and with everyone on earth supposedly singing it …. With Joy speaking over them: O ye millions, I embrace you … and all mankind shall be as brothers beneath thy tender and wide wings.”

Writing shortly after he’d moved to New York in August 1932, James Agee, who was born on November 27, 1909, describes listening at night to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on a phonograph in his office on the 50th floor of the Chrysler Building: “An empty skyscraper is just about an ideal place for it … with all New York about 600 feet below you, and with that swell ode, taking in the whole earth, and with everyone on earth supposedly singing it …. With Joy speaking over them: O ye millions, I embrace you … and all mankind shall be as brothers beneath thy tender and wide wings.”

Typically, the author of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and A Death in the Family balances his swelling rhapsody with some topical reality, referring to “all this depression over the world” and of two feelings the city inspires, “one the feeling of that music — of a love and pity and joy” for people and the other for the “mob of them in this block I live in … a tincture of sickness and cruelty and selfishness in the faces of most of them.”

Coming to the City

Until I started relistening to Lou Reed’s music, I hadn’t intended to write about the singer songwriter and self-described “New York City man” who died at 71 on October 27. My plan, after a birthday nod to Agee, had been to focus on Grace Kelly, whose life is the subject of “Beyond the Icon,” the lavish exhibit that will be at the James A. Michener Museum in Doylestown through January of next year. Although I’m still absorbing Reed’s music, his identification with New York is reason enough to bring him on board. Some 40 years after Agee came to the city, Reed released his best-known solo album, Transformer, featuring “Walk On the Wild Side,” an edgy ode to people drawn to Andy Warhol’s Manhattan domain, namely Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, Little Joe Dallessandro, Sugar Plum Fairy Joe Campbell, and Jackie Curtis. Joining them in two other great Lou Reed songs are “Sweet Jane,” who knows “that women never really faint/and that villains always blink their eyes,” and seven-year-old Jenny in “Rock and Roll Music” who “one fine mornin’ puts on a New York station” and “starts dancin’ to that fine fine music. You know her life was saved by rock ‘n’ roll.”

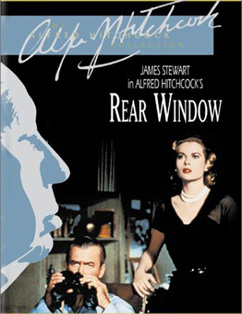

New York was also 18-year-old Grace Kelly’s destination in 1947 when to the chagrin of her well-heeled Philadelphia family (her father saw acting “as a slim cut above streetwalker”) she decided to devote herself to a career in the theater. Living at the Barbizon Hotel for Women might not exactly be a walk on the wild side (men were denied access above the street level foyer), but there were lovers to come, and it’s fitting that her two most memorable performances are in movies with Manhattan settings, The Country Girl, for which she won an Oscar cast against type as the nagging adulterous muse to a drunken actor played by Bing Crosby, and Rear Window, which gave her the sexiest role of her brief career thanks to Alfred Hitchcock’s talent for turning his erotic fantasies into cinematic art.

The Plot Thickens

As for Andy Warhol himself, he came to New York from Pittsburgh two years after Grace’s arrival; meanwhile Brooklyn born Lou Reed grew up on Long Island and definitively entered the life of the city in 1964 after graduating from Syracuse University, where he studied with the poet Delmore Schwartz (“the first great person I ever met”). Reed showed his appreciation by dedicating the Velvet Underground song “European Son” to his mentor and later by composing a tribute called “My House” (“to find you in my house makes things perfect”). Another Brooklyn native, Schwartz had settled in Manhattan in the late 1930s and just as Reed would find himself as an artist in the Warhol/East Village scene, Schwartz flourished through his connection with the Partisan Review, where he befriended the wildly talented, driven, reckless human being laboring for Fortune and Time 50 floors up in the Chrysler Building. As it turned out, James Agee would make his name writing the column on film for The Nation that W.H. Auden dubbed “the most remarkable regular event in American journalism.” Had Agee’s hell-bent heavy-drinking lifestyle permitted it and had he stayed on as a film reviewer into the 1950s, we might have known his thoughts on Grace Kelly and Rear Window, which was released the year before he died and a mere two years before Grace became a princess, an event that Hitchcock helped make possible by casting her in the film (To Catch a Thief) that took her to Monaco.

By now it seems that once New York becomes the common denominator, all bets are off and the plot fantastically thickens. Though he lived outside Manhattan over the years (in Hollywood and up the Delaware River in Frenchtown), Agee was, like Reed and Schwartz, a New York City man right up to the day he died, stricken with a fatal attack of angina in a taxi in May 1955. What more Manhattan-centric place to make your quietus than in a Yellow Cab, commanded in this case by a driver who knew to rush his passenger to Roosevelt Hospital, the same facility to which an ambulance brought another New Yorker of note named John Lennon 25 years later on December 8, a day that coincides with the date of Delmore Schwartz’s birth — a hundred years ago this year.

Hitchcock’s New York

You might say that Hitchcock has “done” New York. There’s Cary Grant in Grand Central Station in North by Northwest (1959), Robert Cummings in the crown of the Statue of Liberty as the villain goes screaming to his death in Saboteur (1942), Grace Kelly as the victim in a New York apartment in a lesser film, Dial M for Murder (1954), Henry Fonda falsely accused in The Wrong Man (1956), Jimmy Stewart in a Manhattan apartment where a murder has been committed in Rope (1948), and most significantly in relation to the myth of Grace Kelly, Stewart is the central character in Hitchcock’s salute to the voyeur in all of us, Rear Window, where he’s in a wheel chair, his leg in a cast, observing with morbid fascination the play of life going on in the windows of the apartment building across the way. The scenario even provides a street address to help situate you, 125 West 9th, but this is strictly a Hollywood Manhattan made on a Paramount sound stage and the most New York thing about it is the voice and vigor of Brooklynite Thelma Ritter.

All Grace

All Grace

Rear Window is adored by Hitchcockians and film buffs in general for exploring the act of seeing, the voyeur as audience; it’s also appreciated for its automat-style tableau of city life (each little window a movie screen featuring the newlyweds, the quarrelling couple, the lonely woman, the composer at the piano, the party, the lady with the dog, the losers and winners, and the act of murder deduced by Stewart’s prying photographer), but the film’s most memorable, most glamorously cinematic moment is all Grace. Nowhere else in her career does the legend so enchantingly shine forth.

Hitchcock takes pride in having deliberately subverted the decorous Princess Grace stereotype. “I didn’t discover Grace,” he has said, “but … I prevented her from being eternally cast as a cold woman.” In an interview with Oriana Fallaci, after nastily disposing of Kim Novak and Vera Miles, Hitchcock has nothing but kind words for Kelly: “She’s sensitive, disciplined, and very sexy. People think she’s cold. Rubbish! She’s a volcano covered with snow!”

That oft-quoted metaphor is unworthy of what happens when we first see Grace Kelly’s Lisa Carol Fremont in Rear Window. This is an appearance, not an entrance, and far more subtle, stylish, and erotic than a snow-covered volcano would suggest. The sequence begins with the camera panning across the vista of windows Stewart has been inspecting; you hear a woman singing scales and you can see people walking and traffic moving on a portion of Ninth Street through a space between the buildings opposite. The disabled photographer in the wheelchair is dozing when a shadow falls over him. The shadow is characteristic Hitchcock, a sly tease leading you to imagine for a second that some malign force is about to descend on the helpless man. After all, this is an exposed first-floor apartment on a steamy Greenwich Village summer evening. But instead of the fearsome source of the shadow bending over its victim, a beautiful face is coming toward us, right at us, filling the screen (still with a hint of the sinister, could be a green-eyed vampire in a nightmare Stewart’s having, red lips parted, lusting for the bared throat), there’s the shadow again flowing over him as his eyes open, he looks up, and sees the luminous face of his lover bending close to kiss him, she in a swooning motion; shown in profile, it’s the epitome of a kiss, promising everything but only promising, as she asks, her lips touching his, kissing each question, how’s his leg, how’s his stomach, and then, smiling sublimely, “And your love life?”

This is the woman in the print Andy Warhol made after Kelly’s death in 1982, less Princess Grace of Monaco than Lisa Carol Tremont, who has definite features in common with Lou Reed’s “Sweet Jane.” Now imagine you’re 50 floors up in the empty Chrysler Building on James Agee’s birthday, it’s late at night, and instead of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy you’re listening to the long version of “Sweet Jane,” the one on Fully Loaded, the expanded version of the Velvet Underground’s 1970 album Loaded, where everyone “who ever had a heart…wouldn’t turn around and break it,” and anyone “who ever played a part…wouldn’t turn around and hate it,”— and the restored lines, all Grace, “Heavenly wine and roses/Seem to whisper to her when she smiles.”

Books consulted were Letters of James Agee To Father Flye and Donald Spoto’s High Society: The Life of Grace Kelly.