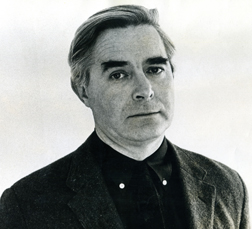

Pairings and Passings: It’s Never Too Late to Read Julian Moynahan (1925-2014)

By Stuart Mitchner

I watched him work in the back house where his study was located, his silver hair framed by the window and I wished I had something interesting to tell him.

—Molly Moynahan

It’s been said that if you throw a stone in Princeton you’ll hit a writer. Molly Moynahan’s picture of her father at work would make a good cover image for a book on the subject: the writer daughter peering wistfully at her writer father in the lighted study window.

Last Tuesday I was checking over the page proofs at Town Topics and there in the middle of the obituaries was a photo of Julian Moynahan. It was a proof to read, a fact of working life, but the room felt different, as if all the air had been sucked out of it. He was 88 and I hadn’t seen or spoken with him for years. In that moment at the window, his daughter wishes she had something interesting to tell him. I’m thinking about what he can tell me in a book I’ve been meaning to read for the better part of 20 years. The only issue was whether or not I still had my copy of his novel from 1963, Pairing Off. As soon as I got home, I hurried down to the unsorted no-man’s land of books in the basement, my former study, where, to my great relief, I found it, and a good thing, too, because the Princeton Public Library no longer has a single one of his four novels, nor his study of D.H. Lawrence, nor his Princeton University Press book on Anglo-Irish literary culture.

The last time I remember talking with Julian was in that “back house” mentioned by his daughter Molly. I’d been there to pick up several bags of donations to the Friends of the Princeton Library Book Sale. Since most were review copies from his days writing for the New York Times, the Observer and numerous other newspapers and journals, his scribbled notes could be found tucked between the covers and sometimes penciled in the margins. Now here I am scribbling notes and marking up the margins in my copy of Pairing Off.

Visions of Julian

Led by Richard Poirier, the English Department at Rutgers was an exciting place to be in the late 1960s. Arguably the best-looking man in the department, Julian was the one who made you think of terms like “dashing,” “breezy,” “witty,” and “roguish.” He was, in other words, refreshingly counter to the remote, buttoned-up academic, which is why I wasn’t the only grad student who felt comfortable calling him by his first name, a liberty we were less likely to have taken with his colleagues. Julian has always been Julian, never Mr. Moynahan, never Professor Moynahan, and, perish the thought, never Dr. Moynahan.

The first time I had a real conversation with him was at a cocktail party where he was, as they say, in his cups, three sheets to the Irish wind, feeling no pain, etc. etc., while serving up juicy slices of literary gossip. In time I would see a more subdued Julian the evening he hosted and fed the members of his D.H. Lawrence seminar at his home on the Princeton-Lawrenceville road near Squibb, the model for the corporate monolith in his third novel, Garden State. His wife Elizabeth and daughters Catherine, Bridget, and of course Molly, must have been visible on the fringes, but all I remember is Julian holding forth near the hearth and the blazing fire like an inn keeper conversant with all things Lawrentian. The daughters turned up again a few years later in the Rutgers suite at the New York Hilton, where he was calmly, even heroically, counseling semi-hysterical job seekers in the high energy environment of the Modern Language Association convention. The girls must have been in their teens, coming and going, red-cheeked and giddy with the afterglow of Christmas in the city. The interaction of father and daughters in that otherwise feverish, monomaniacal atmosphere was refreshing, a breath of fresh air in the MLA hothouse.

The Christmas snapshot of the daughters leads to the saddest image of Julian, the one I will never forget. A decade or more after that particular MLA, my wife and I ran into him while walking on the path along the lake between Kingston and Princeton. Usually we’d have stopped to talk, for it was unusual to see him simply out walking by himself; instead, after saying hello and exchanging knowing glances, we moved on. There was nothing to say. We had only just learned that his eldest daughter, Catherine, had been killed by a hit and run driver while crossing a street in Hoboken.

Dealing With It

I’m still in the dark about the origins of my copy of Pairing Off. The Rutgers University Library sticker inside the front cover states that it was “Presented by Julian Moynahan,” which would suggest that it came to me with the books Julian donated to our library. In effect, I’ve been reading an ex-library copy of a novel that begins in a Boston library, with a librarian protagonist, presented by the author to not one but two libraries. It’s also hard to ignore a certain gallows humor that the author himself might have appreciated, given the fact that he had to die before I finally got around to a book that had been languishing unread for decades in the basement. Most important of all under the circumstances is that death is what Pairing Off is essentially dealing with, at once sensibly, humanely, wittily, touchingly, and undepressingly. The dying of Milly Rogers, friend and lover of the rare books librarian Myles McCormick, is the heart and soul of a novel that ends, happily and improbably, in an Irish cemetery. Being by profession a nurse devoted to terminal patients, Milly herself is an authority on the subject and knows she’s dying more than a year before her clueless, self-involved lover figures it out.

One of the book’s charms is that for all the style, verve, intelligence, and metaphorical fancy the author employs on his behalf, Myles has a tendency to trip himself up, most painfully while courting Eithne Gallager, the other major female character, who also knows a thing or two about death, having lost her husband in a gruesome dockside accident.

At one point Pairing Off pictures a fate for Myles wherein he becomes a “kind father … to rosy-faced and elfin-limbed children, the doting husband of a clever, passionate, beautiful woman as yet unmet but not undreamed of, who would take him not for what he was, but for what he had in him to become” (he finds his dream in the closing chapter). Almost in the same breath, Myles improvises a playfully morbid bit of business about “Milly and Myles Mumblecrust, barkeep and barmaid in the Last Chance Saloon …. Only she had slumped suddenly behind the stained and bulletmarked counter, and he could do nothing for her now but carry her on the last ride to Boot Hill.” Indeed, Myles does everything for Milly, holds a wake, attends to her dying wishes, and carries her ashes on the last ride from Boston across the Atlantic to the Irish cemetery.

The closest Pairing Off comes to taking sentimental advantage of the situation actually provides one of its finest moments, when Myles buries Milly, the dust of death’s truth in his hand, and is “swamped by a feeling of wild, desolating tenderness” for her, wishing “that he had held onto her, gotten in bed with her to warm her … as her life lapsed, been with her then like a husband, or at least a lover, or even a brother.” It’s at the moment of this admission that the author blindsides the guardians of probability with the help of a Greek fairy godfather who produces Myles’s dreamed-of woman as if to reward him for that seizure of “desolating tenderness.”

Although the denouement of the novel is prefaced by an italicized meditation on its title — “Pairing off is the fate of mankind” — the darker truth behind the phrase is suggested earlier in the narrative after Milly dies: “He wondered how he would die, whether he would die alone, and knew there was no other way of dying.”

Father and Daughter

In the passage about watching her father at work, Molly Moynahan also refers to his first novel, Sisters and Brothers (1960), “a stunning account of the experience of a young boy who spends a year in a terrible orphanage while his mother struggles to support the family after his alcoholic father has disappeared.” She finds the novel “painful to read, but even more painful” when she learns from her mother “that his book was close to an autobiography. He had never told us anything about all that, and whatever he did to be a full scholarship student to Harvard remained unspoken, as well.”

The idea of revelations untold or unspoken brings to mind the daughter’s wish that she had “something interesting” to tell her father. One way to tell him would be to write three novels. Perhaps that’s what makes her recall the time her third book had been published and she was to give “a hometown reading in Princeton” at which Julian would introduce her. She was nervous because “most of the crowd” had known her “forever.” Father and daughter were sitting in the car together, parked across the street from where she’d been born. When she admits she’s scared, he tells her not to worry, that it’s a good book: “You worked hard …. I’m very proud of you.”

The quotes from Molly Moynahan were found in an article on Neworldreview.com. She also writes for the Huffington Post and at Mollymoynahanblogspot.com.