Nights of Wonder: Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in Hollywood and Beyond

By Stuart Mitchner

The reading of this play is like wandering in a grove by moonlight ….

—William Hazlitt (1817)

Hazlitt ends his short essay on A Midsummer Night’s Dream by suggesting that “Fancy cannot be embodied” on the stage “any more than a simile can be painted ….The boards of a theatre and the regions of fancy are not the same thing.” In other words, the act of reading allows imagination full play while a staged performance turns “an airy shape, a dream, a passing thought” into “an unmanageable reality.” Hazlitt compares the stage “to a picture without perspective” where “everything there is in the foreground.”

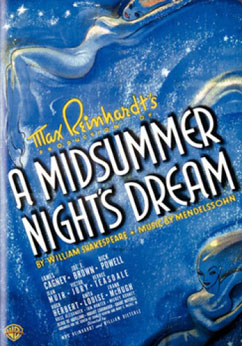

Some 34 years into the 20th century, an Austrian theatrical director named Max Reinhardt brought Shakespeare’s “regions of fancy” to life on a Warner Bros. soundstage in Burbank, California. While there’s no knowing what Hazlitt would have made of a cinematic spectacle that sweeps foreground and perspective into luminously fluid new configurations, he’d have most likely been both appalled and amazed. Perhaps once he’d adjusted to the boundless new medium, he would have calmed down enough to appreciate James Cagney’s ecstatic Bottom, a character he called “the most romantic of mechanics” and one “that has not had justice done him.” As for Mickey Rooney’s Puck, “a mad-cap sprite,” as the essay has it, “full of wantoness and mischief,” Hazlitt would see that fancy could indeed be embodied much as he’d described it, “borne along … like the light and glittering gossamer before the breeze.”

Mickey Rooney (1920-2014)

Mickey Rooney (1920-2014)

When I heard the news of Mickey Rooney’s death, my first thought was not of Andy Hardy or Boy’s Town or his M-G-M soulmate Judy Garland, but of his performance as Puck. By all rights, Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, co-directed with William Dieterle, should be a Hollywood milestone, universally acknowledged, admired, and discussed, like The Wizard of Oz, which was made five years later at M-G-M and has as its source a book for children written by L. Frank Baum, and with music by Frank Loesser. Dream comes from Shakespeare, with music by Felix Mendelssohn, an unbeatable combination, you might think. In fact the stigma of those names scared off audiences and alienated reviewers who considered themselves protectors of Art, dismissing Warners’ Shakespearean adventure as overblown airy-fairy folderol. According to one of the most intelligent reviewers of the day, Otis Ferguson in the New Republic (16 October 1935), any film that runs “well over two hours,” costs “more than a million,” and was “press-agented for months ahead” is doomed to be discussed by “culture clubs” and critics who “will put on their Sunday adjectives,” and as for “American husbands,” as soon as they “get one load of the elves and pixies,” they’ll go back to the “sports page.”

Ferguson singles out Rooney’s Puck as being “too ill instructed and raucous to be given such prominence.” This is a 14-year-old half-naked youth in the grip of his demon, a creature David Thomson calls “truly inhuman, one of the cinema’s most arresting pieces of magic.” Rooney does have some raucous moments in the roles that made him the most popular male star of the late thirties, but if you revisit any of his M-G-M films, you’ll see how thoroughly his lively genius has been contained and “instructed” within the regimen of that studio’s polished production values. At Warners, whatever the genre, the actors are given more space, especially when navigating a work of word-drunk virtuosity, whether Shakespeare’s lines are chortled by Rooney or roared by Cagney. It’s fun to see two such in-your-face personalities mining the raw essence of their actor egos, giddy with glee, Cagney a fountain of laughter, Rooney’s “What fools these mortals be” guffaw bubbling up through him with each fantastical prank.

650,000 Candles

Because lighting on the sound stage was a challenge (it’s said that 600,000 yards of cellophane and 650,000 candles were used), cinematographer Hal Mohr sprayed the “67 tons of trees” in Shakespeare’s forest with aluminum paint and covered them with cobwebs and tiny metal particles to reflect the light. In spite of its failure at the box office, the films’s wondrous visuals created enough word-of-mouth excitement that A Midsummer Nights Dream became the first (and last) write-in winner of an Academy Award, for cinematography. It was also nominated for Best Picture.

Olivia’s Debut

Shakespeare aficionados who might wince at the cavorting of Cagney and Rooney should have no problem with Olivia deHavilland, now 97 and one of the few surviving members of the 1935 cast. Dream was her debut and though she’s best known for Melanie in Gone With the Wind and as Errol Flynn’s perennial love interest at Warners, she makes a definitive Hermia. Her plan had been to teach English (she had a scholarship to Mills College) when Max Reinhardt saw her playing Puck in a community theatre production of Dream and cast her as an understudy to Hermia in the version he was staging at the Hollywood Bowl. In true storybook fashion, the other actress dropped out, Olivia got the part, and played it through the entire engagement and a four-week tour, one reason she does full justice to her role.

Shakespeare in the Park

With Shakespeare’s 450th birthday looming a week from today, I’ve been reading in the new Library of America anthology, Shakespeare in America, which includes an excerpt from Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place that offsets Hazlitt’s claim that fancy can’t be embodied on the stage. Something wonderful happens when a weary, embattled single mother named Cora Lee takes her children to see a neighborhood production of A Midsummer Nights Dream directed and performed by African Americans. Based on Naylor’s childhood visit to a Shakespeare in the Park staging of the play, Cora’s experience has an affecting simplicity. At first she “couldn’t understand what the actors were saying,” never having heard “black people use such fine-sounding words” (“and they really seemed to know what they were talking about”). Then, as has happened through the centuries, the setting of the forest scenes (“huge papier-mache flora hung in varying shades of green splendor among sequin-dusted branches and rocks”) casts a spell (“the Lucite crowns worn on stage split the floodlights into a multitude of dancing, elogated diamonds”) that anyone with a sense of wonder would be responsive to: for Cora, it’s “simply beautiful,” even her restless son is “awed.”

Naylor’s account of the action through Cora’s eyes gets down to the basics: “The fairy man had done something to the eyes of these people and everyone seemed to be chasing everyone else. First, that girl in brown liked that man and Cora laughed naturally as he hit and kicked her to keep her from following him because he was after the girl in white who was in love with someone else again. But after the fairy man messed with their eyes, the whole thing turned upside down and no one knew what was going on — not even the people in the play.”

Cora is struck and saddened by the fairy queen’s resemblance to her daughter, who may never go on to college. Worse, Cora and her children are so shabbily dressed that she has to hold them back when the audience is invited onstage to join the cast, “not wanting their clothes to be seen under the bright lights.” As Puck (“the little fairy man”) delivers the closing lines, Cora applauds “until her hands tingled,” feeling “a strange sense of emptiness” now that it’s over.

On the way home, the kids try to “imitate some of the antics they had seen,” one wonders if Shakespeare’s black, and Cora remembers that “she had beaten him for writing rhymes on her bathroom walls.” At home the bedtime ritual goes more smoothly than usual, for “this had been a night of wonders.” In the last sentence, Naylor allows herself a Shakespearean flourish as Cora “turned and firmly folded her evening like gold and lavendar gauze deep within the creases of her dreams.”

And so Shakespeare, as Emerson expresses it, “delights in the world, in man, in woman, for the lovely light that sparkles from them,” and “Beauty, the spirit of joy and hilarity” is shed “over the universe.”

If you’re a determined YouTube searcher, you can find scenes from the Max Reinhardt film online, if not the whole thing. You can also see the Beatles doing their version of the Pyramus and Thisbe play within the play. A long TCM interview with Mickey Rooney in which Puck is never mentioned can be found by Googling watch-mickey-rooney-career-spanning-interview with Robert Osborne. The quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson is from his essay, “Shakespeare, Or the Poet,” included in The Library of America’s Shakespeare in America, which is edited by James Shapiro; the quotes by William Hazlitt are from the Everyman edition of Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays; David Thomson’s is from his Biographical Dictionary of Film (1994 edition).

Saved by the Record Exchange

I found the DVD of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the ever-amazing stock of the Princeton Record Exchange, which can almost always be counted on to come up with CDs, DVDs, and LPs that can be found nowhere else. Record Store Day is coming to Prex this weekend. For details see the story on page 23.