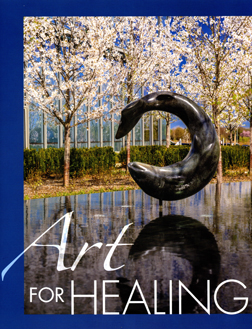

Art Is Part of the Healing Process At the New Hospital in Plainsboro

ART FOR HEALING: At the new University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro, art is playing no small part in patient recovery. Research shows that an environment that includes works of art such as Gordon Gund’s life-affirming sculpture, “Moment,” can help combat stress. Serene images by local artists are all around the building, in corridors and lobbies, waiting areas and patient rooms. And it’s not just patients who benefit, those who work there every day are also finding solace in the artwork. (Image Courtesy of UMCPP).

Art is playing no small part in the process of patient recovery at the new University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro (UMCPP) and local artists feature most prominently among the work on display throughout the building, in corridors and lobbies, waiting areas and patient rooms, and in the Art for Healing Gallery.

The new hospital is not such a surprising place for a collection of artwork as you might at first think. Artists and art lovers have long found solace and comfort in forms of art. Now scientific research is bolstering their intuition by demonstrating ways in which art contributes to healing.

According to Barry S. Rabner, president and CEO of Princeton HealthCare System (PHCS), the design of the new hospital buildings was guided by recent scientific research, which demonstrates the measurable effect that art has on patient recovery. Images of nature in particular, can alleviate anxiety and stress, reduce blood pressure, shorten hospital stays, and even limit the need for pain medication.

A tour of the four conjoined buildings that make up the medical campus (the main hospital, emergency and surgery center, Medical Arts Pavilion, and education building) on Monday revealed that indoor art as well as views onto external gardens with sculpture, not to mention vistas of Princeton set among a landscape of trees on the other side of Route 1, can be seen from multiple vantage points throughout. “Every elevator lobby has a piece of artwork,” said public affairs coordinator Andy Williams, as he described the numerous sculptures, oil paintings, watercolors, and fabric pieces on display, each accompanied by signage with details of the artist and often the donor who made the acquisition possible. Charles McVicker’s 2009 painting, The Sandy Road, for example, was a gift from the Community Connection of PHCS, formerly known as the Women’s Auxiliary.

Flukes, a bronze by the blind sculptor Gordon Gund, takes pride of place in the Meditation Garden, while his Moment, enhances the east entrance to the main hospital building. Ernestine Ruben’s 2008 giclee print with drawing, Waterrings (made possible by Barry Goldblatt) is in the Atkinson Pavilion. Naomi Chung’s 2011 oil on canvas, Mimosa Tree is on the fourth floor in the east elevator lobby and Carol Hanson’s stunning 2010 View of the Delaware from Bordentown distinguishes a lobby space on another floor. Elaine Vrabel’s 2010 pastel on paper, Far View of the Marsh is featured in the Matthews Center for Cancer Care, where you will also find a series by Lucy Graves McVicker.

Cafe visitors, will discover two enormous canvases by Eve Ingalls (also made possible by Barry Goldblatt). Her acrylic on paper, We’ll Leave a Light On dates to 1984, and her oil and acrylic on canvas, Is Someone There to 1995.

It seems that art of some form can be viewed from almost any point in the hospital. This is far from accidental. “When we designed the building, we had art in mind and the specific placement of sculpture and graphic art. We even designed places for them. Besides being beautiful, art can be an effective way of helping people find their way through a building. A huge pink flower is much more memorable than a direction to turn left or right. Art is also placed where people are likely to linger, in waiting areas, in lobbies. Ninety percent of our areas have natural light, which is also shown as having an effect on recovery.”

The “huge pink flower,” referenced by Mr. Rabner is muralist Illia Barger’s large canvas, Natasha, 2009, which provides a focal point at the end of a long corridor and has become a reference point for visitors.

Asked why there was a preponderance of landscapes and organic forms on display, Mr. Rabner explained that the choice was deliberate and was driven by the findings of “evidence-based design.” “A lot of research has shown that art has a measurable impact on the speed of patient recovery and reduce rates of infection,” said Mr. Rabner. “Exposure, particularly to landscapes, can reduce stress and a hospital is a stressful environment not only for patients and their families but also for those who work here every day.”

Still, those choosing artwork for UMCPP’s Art for Healing initiative could easily have gone with cookie cutter reproductions, Monet’s Waterlilies, say, or any number of readily recognizable works of art. Instead, they chose to focus on original works by New Jersey artists.

Made up of physicians and staff members, local art curators and experts from Princeton University and other area colleges, the selection committee included Mr. Rabner, Princeton architect J. Robert Hillier (a Town Topics shareholder), and design expert Rosalyn Cama, who chairs the Center for Health Design, which fosters a respect for natural scenes as well as natural light through its healthier hospitals initiative and its promotion of evidence-based design.

Born and bred in the Garden State, Mr. Rabner is very happy about the committee’s decision. “These are artists who know New Jersey and it is great to be able to showcase the beauty of our Garden State instead of other aspects.”

But none of this would have been possible, he said, without philanthropic support. “If the hospital had to choose between a work of art or a linear accelerator, we would choose the latter, obviously. But we are lucky in having great supporters.” The purchase of artwork is funded by donations to the PHCS Foundation.

The Art for Healing program and a permanent collection boasting some 350 paintings, photographs, sculptures, and other original works by local artists with deep connections to Princeton and New Jersey has artwork by artists familiar to Town Topics readers. Besides those named above, you will find work by Hetty Baiz, Jim Perry, Thomas George, Ernestine Ruben, Yolande Ardissone, Joan Becker, Pier Hein, Francois Guillemin, among others.

In addition to the art on permanent display, UMCPP’s Art for Healing gallery offers rotating exhibitions of work by an artist whose work is in the permanent collection. Each show is up for between three and four months. Currently, “Paper as Canvas: Variations on a Theme,” showcases large pieces by Anita Bernarde, for sale in the range of $575 to $1,250. Twenty percent of each sale benefits the hospital.

Incidentally, if you go to see the artwork, don’t miss the Visitors Chapel on the main floor. It is a serene spot for reflection, whatever your religion, although copies of The Bible and Koran are available as are prayer mats and kneelers.

International Trend

According to Mr. Rabner, the design of the new medical campus illustrates an international trend toward designing healthcare settings that promote healing. The Art for Healing program offers a series of regular talks by experts from the Princeton University Art Museum and is working to engage patients with the arts in the Acute Care for the Elderly (ACE) Unit and, in future, in the Matthews Center for Cancer Care.

On Wednesday, April 23, at 7 p.m. Dr. T. Barton Thurber, associate director for collections and exhibitions will discuss “The Art of Observation: Museums and Medicine Today,” at the hospital, followed by an art tour. Anyone who would like to attend, should call Susanne Hall at (609) 252-8704.

And if you are wondering what happened to Seward Johnson’s lifelike sculpture of doctor and patient, complete with wheelchair, which formerly graced the entrance to the “old hospital” on Witherspoon Street. It can be found just outside an entrance leading to the Medical Arts Pavilion.