On His 450th Birthday: Imagining Shakespeare “Within the Consciousness of Our Country”

By Stuart Mitchner

I think Americans will be fascinated to learn of our deep and early connection to the Bard, how he inspired presidents and incited mobs, and how vivid the legacy of one Englishman’s imagination still sits within the consciousness of our country.

—Meryl Streep

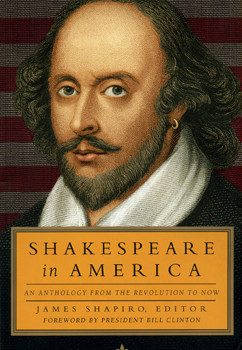

Funny, I was looking through Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now (Library of America $29.95), hoping to find just the right epigraph for this birthday column, and there was Meryl Streep’s on the back of the dust jacket, along with quotes from less celebrated members of the profession mentioning how P.T. Barnum loved Shakespeare so much “he tried to buy the Bard’s playhouse and bring it to America” and how Shakespeare has been “a battleground” where we have “fought about race, anti-Semitism, and gender equality.”

Right, and let’s not forget card games, board games, and movies. Just now I looked through an ancient deck of Authors, the game I grew up playing, where a full book of four Shakespeares was particularly coveted (wouldn’t you know, the only missing card in the deck is Hamlet), and I can’t tell you how many hours my wife and son and I spent playing the board game Shakespeare, rolling the dice and moving the chess-like pieces around in a race to get to the Globe. And the surest route there was to learn the language of the plays.

As for movies …

Hamlet in Tombstone

Garbed in black with the requisite medallion around his neck, Hamlet stands astride a tabletop stage in a Tombstone saloon declaiming the most famous soliloquy in all Shakespeare. The melancholy Dane is being played by a washed-up actor named Granville Thorndyke. As he comes to the line about “shuffling off this mortal coil,” he’s interrupted by a shout of “Enough” from a bearded critter at the foot of the stage who draws his gun and suggests it’s time to stop talking and start dancing. At this, the feared gunfighter Doc Holliday calls out “Leave him alone” and politely tells Mr. Thorndyke to go on. When the actor falters and forgets the lines, Doc Holliday, who has TB, helps him out and takes the speech thoughtfully, movingly, toward “the undiscovered country, from whose bourn no traveller returns” until a coughing fit sends him lunging out the door.

Although the scene described took place on a Hollywood soundstage during the filming of John Ford’s My Darling Clementine with Alan Mowbray as the actor and Victor Mature as Doc Holliday, real-life equivalents have been documented among the touring companies of players performing Shakespeare when the West was still wild. President Bill Clinton’s foreword to Shakespeare in America quotes Alexis de Tocqueville on the Bard’s popularity in the American wilderness, where “there is hardly a pioneer hut in which the odd volume of Shakespeare cannot be found.”

“Hallowed to the World”

Today is William Shakespeare’s 450th birthday. A century and a half ago on April 23, 1864, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who once observed that beings on other planets probably call the Earth Shakespeare, hosted a Tercentennial Celebration at the Revere House in Boston. The poem Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote for the occasion, which is reprinted in Shakespeare in America, speaks of turning away from “War-wasted … strife” of the Civil War to “Live o’er in dreams the Poet’s faded life.”

Three decades later and 1500 miles to the west, Shakespeare’s 330th birthday was celebrated by a University of Nebraska senior writing in a local newspaper to the effect that April 23 had come and gone again, “just as it has done … since it was made hallowed to the world.” After wondering “how many people know or care,” Willa Cather, then not yet 21, narrowed the number down to a few Shakespearean scholars, “a great many professional people, and perhaps the stars that mete out human fate, and the angels, if there are any.”

Also included in Shakespeare in America, Cather’s review of a local production of Antony and Cleopatra takes reverence for the Bard to the limit: “If I were asked for the answer of the riddle of things, I would as lief say ‘Shakespeare’ as anything. For him alone it was worth while that a planet should be called out of Chaos and a race formed out of nothingness. He justified all history before him, sanctified all history after him.”

Another American writer who expressed his passion for Shakespeare in cosmic terms grew up in a small town in Ohio in the 1850s where “printers in oldtime offices” could be heard “spouting Shakespeare.” At the age of 16, William Dean Howells thought that “the creation of Shakespeare was as great as the creation of a planet.” Looking back four decades later, the novelist, editor, and man of letters seems to be chiding “the ardent youth … falling slavishly before a great author and accepting him at all points as infallible,” but in the end he’s drawn back to his early sense of “intimate companionship” with the poet who “in his great heart … had room for a boy willing absolutely to lose himself in him, and be as one of his creations.”

Pumping Up the Sentiment

Among the anecdotal gems in James Shapiro’s introduction to Shakespeare in America is one concerning Ulysses S. Grant, the eventual commander of the Union forces and future president, looking “very like a girl dressed up” in the role of Desdemona for a U.S. Army production of Othello in Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1846. We’ll never know how this extraordinary staging of the play was received, since a professional actress had to be called in when the soldier playing Othello complained of being unable to “pump up any sentiment” with Grant for his Desdemona.

Othello’s wife surfaces as the subject of an essay by another U.S. president, John Quincy Adams, who finds her “unnatural passion” for the Moor to be “a salutary admonition against all ill-assorted, clandestine, and unnatural marriages.”

The short piece by Edgar Allan Poe that follows hard upon the sixth president’s exhortation puts things back in perspective by pointing out “the radical error” of “attempting to expound Shakespeare’s characters … as if they had been actual existences upon earth.” Speaking of Hamlet, Poe brands as “the purest absurdity” the critical urge to reconcile the character’s “inconsistencies” as if he were a living man when in fact “the whims and vacillations … conflicting energies and indolences” are those of the poet.

Nights at the Players

William Winter’s essay, “The Art of Edwin Booth: Hamlet,” includes a letter from the actor in response to someone asking about the “mystery” of Hamlet’s madness, a question Booth says he runs into “nearly three-hundred and sixty-five times a year.” His response is that Hamlet is not mad, which, he writes, “may be of little value, but ‘tis the result of many weary walks with him, for hours together.”

There’s something of Poe’s resistance to “the radical error” in the idea of the actor and the character walking for hours together sorting out “the conflicting energies and indolences” of the poet.

And there’s something of Poe in the 14 days and nights I spent among Edwin Booth’s costumes, props, posters, playbills, and portraits, sometimes imagining I could hear him and his most famous character pacing about on the top floor of The Players Club, which he co-founded in 1888. Lodged there at the behest of my publisher, I was working in a room that was barely large enough for a bed, a desk, a typewriter, a ream of paper, and the godsend of the air-conditioner occupying the bottom half of a window looking out on Gramercy Park and the Metropolitan Tower.

The Players seemed as much Shakespeare’s domain as it was Booth’s, though I was only 20 at the time, too young yet to have bonded with the Bard. Nor was I particularly thrilled to be surrounded by the personal effects of the brother of the man who had killed the most Shakespeare-centric American president, Abraham Lincoln. One of the items I passed every day was a display case containing the letter of apology Edwin Booth had written to the American people after the assassination. I also passed by mannequins dressed in the very costumes Booth had worn when playing Hamlet and Richard the Third. It was not that hard to imagine the “melancholy Dane” haunting the place, or, worse yet, that murderous, child-slaying Richard, who was in my thoughts whenever I passed by a case showing off the bejeweled sword Booth had employed in that role. There were arrays of swords, daggers, crowns, and tiaras flanked by walls crowded with portraits (and the occasional death mask) of actors, writers, financiers, and men about town who had been denizens of the club over time. I could feel those painted eyes staring disapprovingly at me whenever I climbed the carpeted stairway to my room, and none more sternly than the piercing eyes of Edwin Booth himself in the immense John Singer Sargent portrait above the fireplace.

With one happy exception, I never met anyone else on the top floor, thus my uneasy awareness of someone pacing in the hall outside my door when I was sure no one was there. One evening near the end of my stay, I heard a knock that sounded as momentous to me as the porter’s knocking at the gate in Macbeth. Who could it be? Booth or Hamlet or both? Or maybe Richard? Or Booth’s assassin brother who cited Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to justify his act? When I got up the nerve to open the door, I found a jovial, older man on the other side holding out his hand and introducing himself as Edward Everett Horton. Though the name sounded faintly familiar, I had no idea that I was shaking hands with one of the most beloved character actors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. “I hope I didn’t startle you,” Mr. Horton said, clearly aware that he had done just that. It may have been the old actor’s genial, welcoming manner, but after this encounter I felt more at home in the Players, no longer prone to imagine I could hear Edwin Booth and his most famous character making “weary walks … for hours together” outside my door.

Celebrating the 450th

As you might expect, Shakespeare’s homeland is going all out to celebrate his birthday. The Royal Shakespeare Company’s festivities will include a firework display from the rooftop of its theatre, which will follow Wednesday evening’s performance of Henry IV Part I. The display, which is being co-ordinated by leading pyrotechnic experts, will also include “an epic eight-metre-high fire drawing depicting Shakespeare’s face.”

And in New York? Why ask? The theatres of New York, on and off and off-off Broadway represent an on-going celebration of “one Englishman’s imagination.” Speaking of New York, the mob Meryl Streep refers to created a catastrophe in which 25 people died and hundreds were injured. The Astor Place Riots were set off by a dispute between the fans of the American actor Edwin Forrest and English tragedian William Charles Macready. The event is fully documented in Shakespeare in America.