On and Off the Crooked Road of Genius — A Shady Dog Story

By Stuart Mitchner

If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.

—George Harrison, from “Any Road”

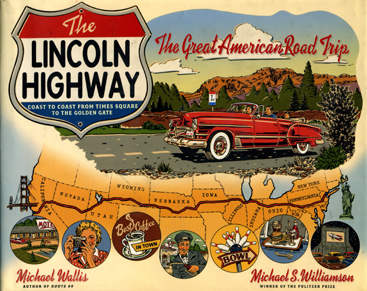

First off, I didn’t know that last week’s trip to the Shady Dog Record Shop would lead to the now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t legend of roadside Americana celebrated in The Lincoln Highway: Coast to Coast from Times Square to the Golden Gate (Norton $39.95). It wasn’t until the day after the trip that I found a perfect match for this column in Michael Wallis and Michael S. Williams’s book, where the introduction, “Mister Lincoln’s Highway,” stresses the “curving and bent, even sometimes warped” nature of the subject by quoting from William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “Improvement makes straight roads: but the crooked roads without improvement are roads of genius.”

Road Music

Though I’m not looking forward to a drive to Berwyn in the northwestern suburbs of Philadelphia, there’s a certain warped, crooked appeal in a destination called the Shady Dog. As usual, my son has brought along some CDs to listen to on the way, and since this trip to a never-before-explored second-hand record store is the coda to a never-ending birthday present, I’m okay with whatever the vinyl warrior wants to hear as we head out of town on 206. Without any apparent intention of playfully linking it to the name of our objective, he suggests The Dog That Bit People, a 1971 album by a group from Birmingham (U.K.). At the moment the only copy of the actual Parlophone original on the market is going for the tidy sum of $2,000. Besides being a reminder of James Thurber’s popularity in England (witness John Lennon’s In His Own Write), The Dog is a nice, solid, melodic, progressive album with a country flavor, it’s indeed easy to drive to, and it’s not worth $2,000.

On the Turnpike

The first time my parents and I drove to New York from Indiana, the Pennsylvania Turnpike opened the way east for us like a dream unimpeded by stoplights and cross roads and frustrations like the pre-bypass endlessness of getting through Columbus Ohio on U.S. 40. Whenever I flash on turnpike moments, it’s night and we’re entering one of those tunnels that to adolescent readers of Ray Bradbury always had a smooth surreal quality closer to sci-fi or the twilight zone than the publicist’s “Magic Carpet Through the Alleghenies.”

But that was then. Today’s 25-mile stretch of turnpike is strictly functional, the best thing about it the poetry of place names like King of Prussia and Valley Forge and Tredyffrin.

Roadside Surprises

The shades-wearing mutt on the Shady Dog sign is just the sort of roadside novelty that used to make traveling fun in the days before turnpikes, interstates, and strip malls. There are other glimmers of roadside America along U.S. 30, which doubles as Lancaster Avenue, but for me the star attraction is the Anthony Wayne, an Art Deco dream of a movie theatre named after the fiery Revolutionary War general who was was born nearby. At first it’s so unlikely an edifice, so eerily out of time, that you can’t quite trust your eyes. Rush-hour gridlock gives me time to take it in. Atop the marquee two sand-colored pillars stand on either side of an elaborately shaped proscenium arch with a scalloped top. Wonder of wonders, it’s not a RiteAid or a CVS, it’s still in use, with five screens. According to cinematreasures.org, when the Anthony Wayne opened its doors as a movie house in 1928, the first feature was a silent, In Old San Francisco. Built and operated by one Harry Fried, the theatre was known for a time as “Fried’s Folly” because “such a grand movie palace” was located “on the edge of the suburbs.” (A sketch of the planned facade design was signed by a young Philadelphia architect named Louis Kahn.)

While another after-the-fact search online tells you all you need to know about Mad Anthony’s tempestuous military career, I’m more interested to learn that the general’s last name inspired Batman’s alter ego Bruce Wayne; that he turns up in Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night as an ancestor of Dick Diver; and that in the opening chapter of The Catcher in the Rye, “old Spencer,” Holden’s history teacher at Pencey Prep, lives on Anthony Wayne Avenue. The great man’s greatest gift to American popular culture, however, involved the ultimate, the one and only iconic Wayne of all Waynes, who in 1930 was still known as Marion Morrison (imagine The Alamo or Red River starring Marion Morrison) when Raoul Walsh, his director on The Big Trail, pulled Anthony Wayne out of his hat, wisely dumping “Anthony” for “John,” and the rest, as they say, is history.

Last Picture Shows

That Deco movie palace in Wayne sends my thoughts back again to the days before interstates and multiplexes when every little town had its own movie theater. On hot summer childhood drives through Indiana, Illinois, Missouri and up and down in Kansas on the flattest and dullest of highways, the great treat for me was to check out the local cinema. Like all red-blooded American kids, I would beg the grown-ups to stop for a Coke and nag them with the eternal “how much longer till we get to so-and-so” mantra, but when it came to movie theaters, I had no shame. It wasn’t enough to simply drive by and look at the marquee and the name of the current attraction. I wanted to stop the car so I could feast my eyes on the posters and lobby cards. I found sustenance for another long hot stretch of road in titles like Johnny O’Clock and actors like Robert Mitchum, whose name in smalltown theater ads was sometimes misspelled as my father’s, Robert Mitchner in Where Danger Lives (there’s a clipping of that one somewhere in the family archives). Now and then you might get fortunate combinations like the Chisholm Trail Theatre in Newton, Kansas showing Fort Apache with, yes, John Wayne.

Looking for the Lincoln

As a college traveler for Norton, the publisher of The Lincoln Highway, I once drove from college town to college town across 11 states from Mississippi to North Dakota earning money for a trip to India. My last night on the American salesman road was spent sleeping in the company car in a Howard Johnson parking lot on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Though nine months of living in motels left me with a sadder but wiser sense of “The Great American Road Trip” spelled out on the cover of The Lincoln Highway, the images of roadside nostalgia depicted there and the red line of the route still rouse all the old feeling. The charming graphics also suggest a benign variation on the earthy art of R. Crumb, who contributed a childhood memory to the book. As a kid in the 1950s, he lived in Ames, Iowa, in “a big old house right on the Lincoln highway … at that time still just a two-lane thoroughfare that went straight through the heart of town. My brothers and I used to sit on the front step of our house and watch the trucks go by. We each had our favorite trucking line and would point and shout its name as it went barreling by.”

Music to my ears. I know what Crumb’s talking about. It all goes back to summers with my maternal grandparents who lived in a house facing on U.S. 69 in Overland Park, Kansas. Some things never change. These days we live close enough to 206 that we can see the cars and trucks going past from our back windows. My wife rolls her eyes when I tell her how much I love the sound of the big rigs that can make conversation on the deck a challenge.

Lincoln’s Among Us

Princeton has a place in the book, by the way. The same Lincoln Highway that begins on Times Square runs right through the heart of town disguised as our own Nassau/Stockton Street and Routes 27 and 206. How odd, that it took a big lavishly illustrated tome to remind me that we can claim not only Nassau Hall and the Battlefield, but the great national road. All these years driving between Princeton and New Brunswick on Route 27, all those nighttime bus rides back from the city, and I never once thought to myself, “Hey, I’m on the Lincoln Highway.” And we were on it again and didn’t know it Thursday driving south on 206 and again, oddly enough, on U.S. 30 in Berwyn and Wayne. Yes, the Anthony Lane and the Shady Dog are on the Lincoln Highway. You may rightly wonder how that can be when U.S. 30 begins its run in Atlantic City before cutting through Camden and Philadelphia to the Main Line suburbs. All I know is after a day that began with us heading south on Lincoln’s route, we landed on U.S. 30 heading west, in the right place at the right time in the national road’s strange slapdash relay race to the Golden Gate.

It works fine if you let it, the idea of a shape-shifting phantom highway named for a martyred president who loved Shakespeare making its mysterious way relentlessly westward, absorbing numbered identities with a Lincolnesque laugh at mandated designations.

If you want evidence of just how devious Lincoln’s road appears to the Philistines, google “Route of the Lincoln Highway” and consider Wiki’s boxed notice declaring “This article or section is written in the wrong direction. U.S. road articles are generally written in a south-to-north and west to east direction in order to follow the order of their mileposts. Please help by rewriting the article in the right direction.”

Do you believe it? East to West the wrong direction? And North to South? Time to listen to George Harrison’s joyous song “Any Road,” which opens his posthumous album Brainwashed telling us “we pay the price/with the spin of the wheel, with the roll of the dice.” We may not know where we came from, may not know who we are, may not “have even wondered” how we “got this far” but here comes the chorus, all join in, “if you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.”