“My Stars Shine Darkly Over Me” — Shakespeare Says It, Charlie Parker Plays It

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

A soft summer’s day in New York. When the rain falls, you can count the drops. I’m sitting on a bench in Tompkins Square Park reading Twelfth Night as a drop kisses the page, then one or two or three more, just enough to ripple the paper. My afternoon in the city began well with the discovery of a shady parking spot on Charlie Parker Place, free for the duration, no $3.50 an hour Muni Meter. My CRV is parked a few yards down the street from the house at 151 Avenue B where the jazz legend lived from 1950 to 1954.

The 1924 Oxford thin-paper edition of Shakespeare’s Works spread open on my lap is bound in soft leather like a Bible, with paper so delicate that it takes a touch as gentle as the rain to separate one page from the other. My reason for reading Twelfth Night; or What You Will (Harold Bloom thinks the secondary title more fitting) is that I’d been planning to write about the centenary of Alec Guinness, who played Sir Andrew Aguecheek at 23 and Malvolio at 55. Everything changed when I found that parking spot on Charlie Parker Place. It’s a “what-you-will” situation, by way of the “divinity that doth shape out ends.” Goodbye Sir Alec (for now), hello Shakespeare, hello Charlie Parker.

On this balmy Thursday afternoon everything makes Shakespearian sense, the diffidence of the rain, the interplay of sun and shadow, the sparrows’ chirping, the pigeons rumbling, a society of dogs romping in the dog playground, children squealing and screaming, a jazzy free-for-all of a comedy from 1601 spread open before me in bold black type on white India paper, and less than a stone’s toss to my left, the austere three-story brownstone rowhouse from 1849 where dwelt the man named on plaques from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the New York Landmarks Preservation Foundation. The latter plaque notes the Gothic Revival style of the residence, “a style most often used for churches,” and refers to “the world-renowned alto saxophonist” and “co-founder of bebop.”

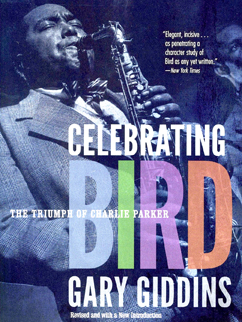

Jazz critic Barry Ulanov called him “the Jazz Mozart,” and Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz said he was “the jazz world’s Mozart” because he “gathered together” the styles that had come before and transformed them into “a brilliant new design,” everything “fresh and whole” and “precisely right.” When Gary Giddins cites Mozart at the conclusion of Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker (University of Minnesota Press $17.95), he’s thinking of more than the music: “As with Mozart, the facts of Charlie Parker’s life make little sense because they fail to explain his music. Perhaps his life is what his music overcame. And overcomes.”

But Mozart isn’t enough. For the music, you need to bring in, among others, Bach, Beethoven, Liszt, Chopin, Debussy, Stravinsky, Gershwin, Cole Porter, Moondog, and the Rubiyat, which contains a stanza Parker was fond of quoting, the one that ends “the Bird is on the Wing.”

“That strain again!”

When it comes to quoting, however, there’s nothing to equal the supple book of riches in my lap. For instance the opening line of Twelfth Night, “If music be the food of love, play on!” And in the same speech, the most eloquent player of them all, he whose 450th birthday is being celebrated this year, plays on: “That strain again! it had a dying fall/it came o’er my ear like the sweet sound/That breathes upon a bank of violets” and over and among the flowers blooming in Tompkins Square.

The “dying fall” will make Bird sense to listeners who recall the dismissive moves the master performs in mid-flight, when as if to relieve himself of a cluster of “nipping and eager” notes, he simply drops them and soars on. He says it himself — “There’s too much in my head for this horn” — in Robert Reisner’s oral history, Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker (DaCapo 1991), where he tells Charlie Mingus “Would you die for me? I’d die for you.” It’s easy to hear a cadence resembling that one-two punch in the mid-flight moments that sometimes move audience members at certain crudely recorded club dates or concerts to shout, “Kill yourself!” Knowing his days were numbered, it was as if he had a special claim on death. More than once, as recounted by friends and acquaintances in Reisner’s book, he says his goodbyes days and months before 8:45 p.m. on March 12, 1955. Again, Shakespeare has a phrase for him — in Twelfth Night when Sebastian says “My stars shine darkly over me.”

Family

What sort of a family life did he lead with his white common law wife Chan in the ground floor of the brownstone at 151 Avenue B? His stepdaughter Kim, for whom he named one of his fastest, happiest compositions, remembers a black bedroom, a fireplace with a white death mask above it, and “family Sundays, family dinners.” In an online interview with Judy Rhodes, the eventual owner of the house, Kim remembers “Bird was a really wonderful father — very kind, very gentle with me.” When she was in first grade at a school “two or three blocks up the street” and had to make her own lunch and walk there by herself, she was “a nervous wreck” and would throw up every morning, prompting the school to send a note home demanding that she see a doctor. Her stepfather took her to an MD on 10th Street who said she was “terrified and needed to be reassured.” So “Bird walked me back to school and back to my classroom. I had no sense of colour or prejudice. When I walked into school holding my daddy’s hand I was at the top of the world — walking with this big Black man into the classroom full of little white snotty kids that I was terrified of. Being there with my daddy made it all ok.”

In Celebrating Bird, Gary Giddins quotes tenor man Al Cohn’s recollection of a visit to Avenue B (“They had a very nice place”): “It was a Ukrainian neighborhood and we went to three or four different bars. All the Ukrainians, working-class guys, knew him as Charlie. I don’t think they knew he was a musician, but it was obvious they liked him and were glad to see him. I saw a different side of him; he was like a middle-class guy with middle-class values.”

Interviewed in Ken Burns’s documentary Jazz, Giddins points out the daily challenge Charlie Parker faced during this period. He had to live three lives: the working musician, the drug addict constantly scuffling to raise money for a fix, and the family man.

The Open Door

Robert Reisner begins Bird with an account of his first meeting with “a large, lumbering, lonely man, walking kind of aimlessly” on a rainy night in 1953. It was just after midnight, Reisner was coming home from a party when he recognized Parker and wondered what he was doing “in this poor Jewish neighborhood, walking by himself in the soaking rain.” Parker said his wife was having a baby and he was walking off his nervousness. Asked where he lived, he said “In the neighborhood, Avenue B,” and seeing that Reisner wondered why “a guy of his tremendous reputation lived in such an out-of-the-way poor section,” he explained, “I like the people around here. They don’t give you no hype.”

Later, after Reisner decided to stop teaching art history at the New School to become a jazz promoter, the venue he picked was The Open Door on 3rd Street south of Washington Square, a place “that had enough seating capacity to pay for a band solely on admissions.” He launched his first “Sunday jazz bash” on April 26, 1953. Three months later, Chan left 151 Avenue B with the tape recorder she’d been given for her 28th birthday the month before. According to the liner notes for the 2-CD set on Ember, Charlie Parker at the Open Door, the tapes Chan made were stored away until she sold them to Columbia Records where they remained for decades in the vaults until they were smuggled out and released in Italy on the Philology label.

My copy of the Open Door performance has been sitting on the shelf for years. One reason is the poor recording quality. It sounds as if Bird and the band, in particular Art Taylor, the drummer, are playing in two different rooms, and on some of the uptempo numbers the drums seem to be crashing randomly about in a void. One of the perks of studio albums that include retakes are those moments when you hear a glitch and everything stops as Bird shouts “Hold it!” But in this acoustical shipwreck of a setting he has to keep bravely blowing, which is what gives low-grade live recordings an existential subplot. It takes several numbers to adjust to the unreality, but with “The Song Is You” the man from Avenue B takes command, changing the “You” to “Me,” and when he gets to “Ornithology,” you hear what Giddins calls “the uncorrupted humanity of his music.”

Shakespeare’s Weaver

It isn’t really all that much of a stretch to speak of jazz in the same breath as Twelfth Night because, as in other Shakespearian romps, the effect is that of a group of players jamming, drunk on the elixir of language. Between Feste the Clown, Fabian, the hapless Sir Andrew, the perpetually soused Sir Toby, and the madcap diva Maria, you have the equivalent of an extended cutting session, or at least that’s how it seemed reading Shakespeare on a Tompkins Square park bench off Charlie Parker Place. For now, listen to Sir Toby Belch in Act 2, when after the clown sings “Youth’s a stuff will not endure,” Sir T suggests rousing “the nightowl in a catch that will draw three souls out of one weaver.”

In case we need an explanatory note for Toby’s flight of fancy, the 1836 edition, the one Melville used, provides this: “Shakespeare represents weavers as much given to harmony in his time.”

And so it is at the Open Door on the night of July 26, 1953, as the weaver of souls, the stars shining darkly over him, plays on.