Of Mice and Men and Player Poets — Alec Guinness at 100

By Stuart Mitchner

An actor is an interpreter of other men’s words, often a soul which wishes to reveal itself to the world but dare not, a craftsman, a bag of tricks, a vanity bag, a cool observer of mankind, a child, and at his best a kind of unfrocked priest who, for an hour or two, can call on heaven and hell to mesmerise a group of innocents.

—Alec Guinness (1914-2000)

Sir Alec Guinness would have enjoyed our mouse. More than that, he’d have been studying it, absorbing its essential mouseness, the intensity of its beady-eyed hold over two fascinated humans and two frustrated felines. For the better part of 20 minutes, the mouse occupied a miniature proscenium formed by the frame at the top of the bedroom window, poking its head over the lacy fringe of the curtains as it stared down at the brother and sister tuxedo cats glaring up at it. Every now and then the little rogue would run teasingly back and forth along the top of its curtain-rod runway or skitter up and down the outer fringe of the curtain before leaping onto a nearby wall hanging, where it was finally trapped in a plastic container and delivered to the wild the following morning.

For Sir Alec, the anthropomorphic fun would have been secondary to a meditation on what it was to be “in and of” such an agile life-form. “I go to the zoo,” was his answer when asked about “building a character” during a 1977 television conversation with Michael Parkinson. While working out the part of the Prufrock-turned-criminal in The Lavender Hill Mob, he visited the small rodent house, fixing his attention on “a nervousy little character rather sort of fluffy” and thinking “maybe something on those lines.” Looking for ideas when playing crookbacked Richard the Third onstage in Canada, he came to a zoo “every two or three days” to commune with “The Unsociable Vulture.” You can see hints of the bird-of-prey in the capacious hovering presence of his Fagin in Oliver Twist (1948), the role that launched his film career. There’s also an aspect of the Unsociable Vulture haunting his Malvolio in an “unfortunate” television production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (1969).

“I Hate Great Acting”

Well into his memoir, Blessings in Disguise (Knopf 1986), Guinness delivers the sort of statement you’d expect to see at the beginning of the book. Recalling the words of actor/writer Alan Bennett — “I hate Great Acting” — he writes, “I know what he meant: the self-importance, the authoritative stage position, the meaningless pregnant pause, the beautiful gesture which is quite out of character, the vocal pyrotechnics, the suppression of fellow actors …, the jealousy of areas where the light is brightest, and above all the whiff of ‘You have come to see me act, not to watch a play.’”

The quality setting Guinness apart from most of his stage and screen peers is articulated in Keats’s definition of the poetical character, which has “no self” but is “every thing and nothing,” delights as much in playing “an Iago as an Imogen,” has “no Identity” but “is continually in for — and filling some other Body.”

Guinness also kept faith with Hamlet’s instructions to the players, not to “out-Herod Herod,” nor to “tear a passion “to tatters,” but rather to “use all gently” to “acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness” and like Keats’s “chameleon poet” to enjoy “light and shade” and live “in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated.”

A Very Literary Man

Shakespeare, Dickens, and Keats were divinities to Guinness, who was, as Gore Vidal observed first-hand during the filming of The Scapegoat, “a very literary man.” The actor visited the poet’s grave in Rome before, during, and after the Second War, and undoubtedly read Keats’s letter defining the “poetical character.” Guinness not only loved poetry and literature, he lived it as a writer and reader, which is why Blessings in Disguise is one of the best books ever written by an actor, not so much for what you learn about acting, which is a great deal, but for the characters brought to Dickensian life in every chapter.

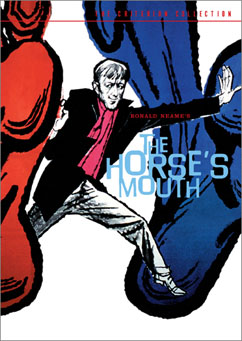

Guinness’s working interest in literature was not confined to the United Kingdom. In 1945, back from a tour of duty as an officer in the Royal Navy, he took on the formidable challenge of adapting The Brothers Karamazov for the stage, and although he terms the result “loose” and “lopsided,” the play was staged at the Hammersmith Lyric and directed by a young Peter Brook, with Guinness himself as the volcanic Dmitri. The year before the war he had adapted Great Expectations, which ran for six weeks after “a splendid notice” from James Agate. The adaptation for which he received the most attention, however, was Joyce Cary’s novel, The Horse’s Mouth, which he mined for one of his most memorable film roles. As Piers Paul Read notes in the 2003 biography, Alec Guinness, “the precise punctual, modest, conventional, buttoned-up Alec Guinness” played “the anarchic, boastful, egotistical painter Gully Jimson.” It was quite a coup, to write your own role on your own terms and receive an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay while winning Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival and coming in second for Best Actor in the 1958 New York Film Critics Circle Awards.

The B-Word

When playing Fagin and Gully Jimson, Guinness speaks with uncharacteristic volume and vehemence; two such vivid characters almost demand to be performed. The risk in underplaying, in being too fine, too subtle, is the b-word. Discussing how to present Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai with director David Lean, Guinness flared up when Lean suggested that Nicholson would be “an awful bore” were they to meet him in a real-life situation (“You’re asking me to play a bore…No, I don’t want to play a bore”). The pernicious word surfaces again a decade later and suggests why Guinness remembered the television production of Twelfth Night as “unfortunate.” In Blessings in Disguise, he recounts watching a run-through of the film in the viewing box with Laurence Olivier, who zinged him thus: “Fascinating, old dear. I never realized before that Malvolio could be played as a bore.” Stung, Guinness heard the word “bore” running through the rest of his performance. According to Read’s biography, the production “left Alec on the verge of a breakdown, physically, mentally, and spiritually. To recover, he spent 24 hours alone in a suite at a grand hotel in Brighton.”

Any actor who does justice to a character as complexly fashioned as Malvolio deserves a weekend of downtime in a grand hotel. Harold Bloom sees the insufferable puritan as Twelfth Night’s “great creation” (along with Feste), pointing out that by the end “it has become Malvolio’s play.”

On YouTube there’s a sample of Stephen Fry’s Malvolio from the Globe production of Twelfth Night that migrated to Broadway last fall. The clip is from the denouement of the practical joke as Malvolio, gulled by a forged love note, struts before Olivia, the countess he serves, crooning and kissing his fingers at her while showing off his cross-gartered yellow stockings. Fry takes it over the top, milking the audience for laughs, no “bore” he. But Olivier was right, Malvolio is a bore, at least until he finds the forged letter. And so Guinness plays him, perusing and reading aloud the letter, which becomes in effect the script giving him, the actor/character, excellent material, his lines and cues, everything a plodding “bore” needs to appear light and amusing. In theatrical terms, this buoyant transformation allows him to take possession of the scene and eventually lay claim to the tragicomic soul of the play. Guinness is too subtle and wise an actor to milk the prank for laughs, though he enters like a peacock (remember his visits to the zoo), showing off his gaily embellished legs, at first plodding Big-Bird-like, but then stepping lightly, capering, almost Chaplinesque, coyly dandling a yellow-stockinged ankle. It’s his moment. And so his dark unfunny fate is to be “notoriously abused,” treated as a lunatic, and locked in a dark cell. Any actor playing Malvolio for laughs in the scene where he cluelessly struts his stuff is out of touch with the element of the play’s genius, its uniqueness, a work so deep that, as Bloom observes, “One cannot get to the end of it because some of the most apparently incidental lines reverberate infinitely.”

A Different Hole

The Criterion DVD of The Horse’s Mouth features a talk with the director, Ronald Neame, who died in 2010 at the age of 99. In marveling at the intensity with which Guinness attacked the part of Gully Jimson and his determination to become the character (his wife complained, “He won’t even clean his nails”), Neame tries to find words for Guinness’s uniqueness. I was struck by the figure he used more than once to describe Guinesses’s chameleon-like ability to “change colors” from part to part: “He comes out of a different hole every time.” In fact, the oddly resonant metaphor was suggested by Guinness himself. As Neame admits in a 2003 L.A. Times interview: “We knew that whatever Alec said he could play, he could play. You’d send him books and he’d say, ‘I’m immensely sorry, Ronnie, but I’ve done this. I don’t want to come out of the same hole. I have to come out of a different hole.’ “

Sort of like, you know, a mouse.