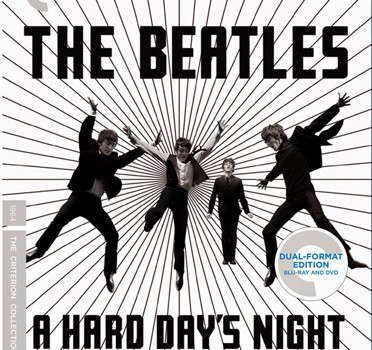

The Beatles and “A Hard Day’s Night” — Fifty Golden Years Making the World a More Companionable Place

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

When the closing credits of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood came on the screen at Princeton’s new community cinema Friday, people applauded. The Garden was full to overflowing, an extraordinary turn-out on a midsummer night, with the students away. The applause suggests that Princeton finally has a place where people go to share movies, not just to see them.

Fifty years ago this month, when the lights came on at Manhattan’s Trans-Lux East on 58th Street after a showing of A Hard Day’s Night, it wasn’t the clapping and cheering that told the story: it was the smiling. Wherever you looked there were happy faces. People were glowing, all ages sharing the euphoria, smiles here, there, and everywhere, a sense of unbounded excitement, such a surge of good feeling you thought it might be powerful enough to conjure up a personal appearance by Paul, John, George, and Ringo.

Not a Fan

At the time of that first viewing I was not a fan. It would be two years before I even owned a Beatles album. My heroes were Sonny Rollins and Charlie Parker. The Indiana couple I talked into seeing A Hard Day’s Night with me that first time weren’t into the music at all, even at the Top 40 Cousin Brucie level, but when we walked out of the theater, they were beaming like everybody else. By now I knew this was a film I didn’t want to see on my own; such joy had to be shared. I’d been living in the city just six months and my only other friend was a tall, super-talkative poet who had zero interest in popular music. She, too, had to be talked into going. So we went. As the picture ended, she said, “Let’s see it again, okay?” and we did. Next up was my best friend, who lived in New Haven, I paid a visit, stayed over, and he and his wife and I went to A Hard Day’s Night, and came out smiling in the afterglow, everyone giddy and loose, the same as the first time in New York. I was beginning to feel like a tour guide for the Fab Four.

Even people predisposed to hate the film loved it. Like that stodgy Elmer Fudd of film reviewers Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, who begins his review by saying, “This is going to surprise you — it may knock you right out of your chair — but the new film with those incredible chaps, the Beatles, is a whale of a comedy.” Who could believe it! The chronically buttoned-up Bosley who had scorned “the juvenile madness” afflicting “otherwise healthy young people” found the “good humor” and “rollicking, madcap fun” created by those incredible chaps “awfully hard to resist.” You had to think, “Something special is going on here,” something, you might even say, magical.

Liberation

Whatever you call it — serendipity might be preferable to magic — A Hard Day’s Night would not have been possible without an expatriate Philadelphian named Richard Lester, who had directed The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film (1960), a surreal 11-minute short starring Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan that was admired by the Beatles, and key to their comfort level with Lester and their own ideas about the zany ambience of the film being created around them.

If anything, The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film looks labored and limping compared to the pace and fervor and comic spirit of its rocking running jumping offspring. Take the romp in an open field scored to the full-tilt frenzy of “Can’t Buy Me Love,” where the film picks you up and runs off with you. Poet/critic Geoffrey O’Brien remembers walking into the theater “as a solitary observer with more or less random musical tastes” and coming out “as a member of a generation sharing a common repertoire with a sea of contemporaries, strangers, who suddenly seemed like family …. The world became, with very little effort, a more companionable place.” O’Brien’s response to the romp in the field was that “the effortlessness” of it “began to seem a fundamental value. That’s what they were there for: to have fun, and allow us to watch them having it …. The converted choose the leap into faith over rational argument. It was enough to believe they were taking over the world on our behalf.”

Charmed, I’m Sure

Imagine how it felt for first-time audiences when A Hard Day’s Night came rushing headlong at them on the wings of the iconic chord producer George Martin considered “the perfect launch,” the four lads pursued by howling teen and subteen furies, diving onto a train at Marylebone Station, driven by a breathtaking display of cinéma vérité virtuosity, genius editing, and dazzling interplay between a group of gifted non-actors from Liverpool and old pros like Paul’s grandfather, the “clean old man” played by Wilfrid Brambell, a leering embodiment of mischief straight out of an Alec Guinness Ealing-era comedy.

Everyone interviewed for the Criterion DVD, from the United Artists and EMI brass to the players of small parts, from Richard Lester to George Martin, is reduced to gushing wonderment at how splendidly the Beatles handled the challenges and demands of making a film on a tight schedule and how well they worked with professional actors. The qualities that charmed the world — the style, wit, sense of fun, sheer energy, not to mention the singing and playing — clearly also charmed the people on the set.

Speaking of charm, there’s the first song after the title number, the only one that grows naturally out of a situation unrelated to the television special the group is seen rehearsing for and performing. Composed and sung by John Lennon, “I Should Have Known Better” is delivered with such joyous force and feeling that your spirits, already high from that opening rush, are lifted even higher, and when John and Paul go up the scale to maximum euphoria singing “Can’t you see? Can’t you see?,” you’re up there with them. Every time I see the baggage car sequence I find more to admire, partly because of being at first so intoxicated by the music that I took the visuals for granted. Another of their great escapes, though not as acrobatic as the zany freak-out in the field, this one has the Beatles taking refuge from the madness on the train, much of it stirred up by Paul’s trouble-making grandfather, the old rogue having been “jailed” for the duration of the journey. Shot through wire mesh giving the impression of a cage, the scene begins as a game of cards until you hear the sound of John’s harmonica as cinematic sleight of hand turns the cards into guitars and the players into musicians, a music video decades before MTV, with close-ups of John, Paul, George, and Ringo interwoven with shots of their small, formidably cute schoolgirl audience. When John sings, “I never realized what a kiss could be,” you’re realizing what a song could be, everything’s meshing, life and music in motion, then back to earth you come, the cards once again in play, Ringo’s won, and so have we all.

“If I Fell” is another infectious song written and sung by Lennon and marked by movingly unexpected harmonic nuances. “My first attempt at a ballad proper,” John has said. As usual in A Hard Day’s Night, plenty is happening in the background, no one stops to listen, people go about their business, everything coming together, music and life once again subtly, spontaneously interacting.

Smiling Through

Of all the songs from A Hard Day’s Night, the one that has the most personal resonance for me is “I’m Happy Just to Dance With You,” which John wrote for George to sing. What a gift. Maybe John felt generous, maybe he thought it too light (“I couldn’ta sung it,” he claims). What a gift for the world. In Istanbul, feeling lonely and strung-out on my way back from India, I heard the song playing over a loudspeaker at a park near Hagia Sophia. It was a lovely afternoon and as I walked among the people, families, couples, all ages, it was the first time I hadn’t been made to feel like an alien being, the object of hard stares on all sides. People were actually smiling at me, and I realized they associated me, the shabby westerner, with the music that was making them feel good. It was reflected glory, the Hard Day’s Night effect all over again.

Half a year earlier in Katmandu, sick and alone since Christmas Day, I pulled myself out of bed and staggered down the road to the nearest cafe. As I walked into the warm, bright room full of strangers, most of them from the west, hitchhikers like me, Germans, English, Dutch, Japanese, Americans, familiar music was playing. The Beatles, who else, and the song was “I’m Happy Just to Dance With You.” After a week of fever and nothing to eat, I sat down at a table with some people who seemed to know me or maybe they knew me through the music. They could tell I’d been under the weather. This was the first day of the new year. Happy New Year someone said. Happy happy happy, said the music. People were smiling as the song filled the room. It took no effort to feel that the world had become “a more companionable place.” The Beatles had taken it over “on our behalf.”

“Boyhood”

Whenever my son, who was bathed in Beatles from day one, moans and groans about the break-up and at how disappointing the solo output has been since 1970, I keep reminding him that between them John, Paul, George, and to a lesser extent, Ringo, made enough great music in their solo careers, that if you felt inclined, you could put together at least two or three great Beatles albums using the best songs. Over the years, I’ve made provisional selections, thinking one day I might take the time to put together a tape for my son. One of the many reasons I was applauding Boyhood at the Garden the other night was the scene where the father (Ethan Hawke) proudly presents the son (Ellar Coltrane) with “something that money couldn’t buy,” his own CD creation, The Black Album, a “secret Beatles record” he’d meticulously assembled from the solo work, complete with liner notes and playlist. The father’s overkill of presentation as his laid-back son fails to come up with a response worthy of the effort, was among the truest moments in an unforgettable film.

One of the first features to play at new Garden, by the way, was the re-released version of A Hard Day’s Night. This community theatre is the best thing to happen to Princeton in ages. You can find out about joining at www.thegardentheatre.com/membership.php.

The quotes from Geoffrey O’Brien and Ned Rorem are from articles in the New York Review of Books. I also quoted from William J. Dowlding’s ever-useful Beatlesongs (Fireside 1989). You can see the playlist for The Black Album at http://blogs.indiewire.com.