Walking the Earth With Wallace Stevens, The Poet of Our Climate

By Stuart Mitchner

I thought on the train how utterly we have forsaken the Earth, in the sense of excluding it from our thoughts. There are but few who consider its physical hugeness, its rough enormity. It is still a disparate monstrosity, full of solitudes & barrens & wilds. It still dwarfs & terrifies & crushes. The rivers still roar, the mountains still crash, the winds still shatter. Man is an affair of cities. His gardens & orchards & fields are mere scrapings. Somehow, however, he has managed to shut out the face of the giant from his windows. But the giant is there, nevertheless.

Wallace Stevens, April 18, 1904

The poet, who turned 25 on October 2 of the same year, had these thoughts on his way back to New York City after a 42-mile walk from Manhattan to Fort Montgomery, “just failing of West Point.” He walked from seven in the morning until half-past six at night “without stopping longer than a minute or two at a time,” noting “How clean & precise the lines of the world are early in the morning! The light is perfect — absolute — one sees the bark of the trees high up on the hills, the seams of rocks, the color & compass of things.” After observing that “seven is the hour for birds, as well as for dogs and the sun,” he writes, “God! What a thing blue is! It is one of the few things left that bring tears to my eyes (or almost). It pulls at the heart with an irresistible sadness.”

That Stevens’s birthday is this Thursday coincides well with a column written in the wake of the Climate March and the Climate Summit at the U.N. One way to set the crowd cheering at a rally about global warming would be for a charismatic reader to celebrate “the color & compass of things” expressed in the poetry of Wallace Stevens.

Given his fascinating, perverse, and outré world of verse, where “man is the intelligence of his soil,/The sovereign ghost … the Socrates/Of snails, musician of pears,” Stevens never seemed the companionable sort of poet you could put in your pocket and wander in the country with the way you might with, say, Keats and Coleridge. You could see him as E.M. Forster did C.P. Cavafy, standing “at a slight angle to the universe,” but if you read the notebook entries recording epic treks over the Palisades and the Poconos in his mid-20s, you find yourself following someone who strides through the universe in seven-league boots and is still going strong at 63, “like a man/In the body of a violent beast.” The poem, “Poetry Is a Destructive Force,” from Parts of a World (1942), ends as “The lion sleeps in the sun./Its nose is on its paws./It can kill a man.” In “A Weak Mind in the Mountains,” the poet imagines: “Yet there was a man within me/Could have risen to the clouds,/Could have touched these winds,/Bent and broken them down,/Could have stood up sharply in the sky.”

The Old Clothes Man

The hulking 24-year-old who wrote of the earth that “dwarfs & terrifies & crushes” is someone you’d definitely make way for if you were in his path. Here he is February 1906, on his way “to Morristown and back” (meaning he walked from Manhattan and back, about 26 miles): “Yesterday I was in my element — alone on an up-and-downish road, in old clothes, quick with the wind and the cold …. Old clothes men are indescribable impostors and boors — yet I am one of them! … My brain was like so much cold pudding. First, I loathed every man that I met, and wanted to get away, as if I were some wild beast.” What does he find to admire? “A bird on a telephone wire that seemed to enjoy the raking. Good old fellow! … What I did enjoy was the tear on my body — the beat of the blood all over me.”

Later in the same entry, he admits, “I can’t make head or tail of Life. Love is a fine thing. Art is a fine thing. Nature is a fine thing, but the average human mind and spirit are confusing beyond measure …. What a bore to have to think all these things over, like a German student, or a French poet, or an English socialist! It would be much nicer to have things definite — both human and divine. One wants to be decent and to know the reason why. I think I’d enjoy being an executioner, or a Russian policeman.”

He closes that dizzying soliloquy by wondering: “May it be that I am only a New Jersey Epicurean?”

Out of the old clothes man’s mind — Stevens in a nut-shell, like Hamlet: “O God, I could be bounded in a nut-shell and count myself king of infinite space” — come works like “The Poems of Our Climate,” “The Comedian as the Letter C,” “Of Hartford in a Purple Light,” “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” and “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts,” where “The trees around are for you,/The whole of the wideness of night is for you,/A self that touches all edges,” a “self that fills the four corners of night.”

Stevens in the Barracks

A case for a companionable Stevens is made by Anatole Broyard in the Sunday, September 12, 1982, New York Times, where he recalls being “a rookie soldier” in an Army camp, “a barren and featureless place filled with strangers.” At times when “the world was too little with me …. I would go to my footlocker for the poems of Stevens.” While other men in the barracks had brought with them something from civilian life to prove “to the others, or to themselves, who they were or had been,” Broyard brought four volumes of Stevens’s poems: “He had a line for everything that was happening to me. When I looked at the sky, it ‘cried out a literate despair.’ The life I led in the Army was ‘a revolution of things colliding.’ I had no doubt that ‘these days of disinheritance, we feast on human heads.’ I saw myself caught ‘in the glares of this present, this science, this unrecognized, this outpost, this douce, this dumb, this dead.’ We were not allowed off the post during basic training, and Stevens was my favorite means of escape.”

Quoting Frank Kermode on “The Comedian as the Letter C’’ (“a sustained nightmare of unexpected diction”), Broyard says “Nothing could have suited me better, because the talk in my barracks was a sustained nightmare of expected diction.”

Boxing With Hemingway

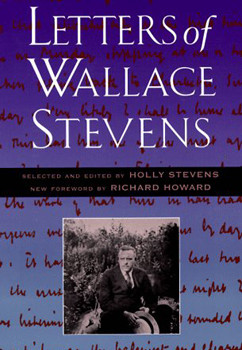

One odd example of “unexpected diction” in the Holly Stevens’s edition of her father’s letters (Knopf 1966) is his reply in July 1941 to a friend on the Princeton faculty who was looking for someone to lead a lecture series on “actuality.” After discussing several more conventional possibilities, Stevens recommends Ernest Hemingway. “Most people don’t think of Hemingway as a poet,” he explains, “but obviously he is a poet and I should say, offhand, the most significant of living poets so far as the subject of EXTRAORDINARY ACTUALITY is concerned.” Stevens, who more than once puts the words in capital letters, goes on to speculate on the fee Hemingway might require. “My guess is that … if he understood that Princeton was merely a place to speak on the subject and that his audience was to be merely a group of young men exactly like himself, interested in the same thing, he would come for, say, $500.”

It feels like entering a Stevens poem simply to imagine Hemingway, who as far as I know never gave a lecture in his life, presenting one on the subject of “extraordinary actuality” to a Princeton University audience, never mind the fee. The elephant in the room of the Hemingway-Stevens story, such as it is, concerns the incident five years earlier when the two men fought it out on a street in Key West. Stevens broke his hand on Hemingway’s jaw after which Hemingway knocked him down, more than once. The insurance executive was 20 years older, and, one would assume, less fit than the sportsman/novelist. Hemingway boasted about it, even giving his opponent’s dimensions, 6’2, 220 pounds, as if Stevens were a lion he’d brought down in the wild. The way Hemingway tells it in a letter, Stevens had said unpleasant things about him to his sister and had come looking for a fight at the same moment Hemingway was on his way to start one. The most curious detail is that Hemingway was wearing glasses and Stevens did not make his move until Hemingway took them off. Perhaps Stevens, like his younger, “old-clothes-man” self, was in a “loathing every man” mind-set when Hemingway walked into his path.

Walking

It seems likely that Stevens’s inclination for the unexpected was nurtured during those compulsive perambulations of his youth. In a New York Times interview with Lewis Nichols the year before he died, Stevens says, “I just write poetry when I feel like it. I write best when I can concentrate, and do that best while walking. Any number of poems have been written on the way from the house to the office.” But with a force as stately and surreal as Stevens, a mere house and office are not worthy. “Setting out on Stevens for the first time,” Randall Jarrell wrote, “would be like setting out to be an explorer of Earth.”

In his essay, “Imagination as Value,” Stevens observes that while the world may be “lost to the poet … it is not lost to the imagination … because, for one thing, the great poems of heaven and hell have been written and the great poem of the earth remains to be written.”

I found the notebook accounts of Stevens’s rambles in Souvenirs and Prophecies, The Young Wallace Stevens, edited, again, by Holly, whose nature-rooted name will come as no surprise if you read in and about her father.