“Every Little Thing” — With the Beatles in India, Songs and Stories of Rain and Shine

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

“They were rather war-weary during Beatles for Sale. One must remember that they’d been battered like mad throughout ’64, and much of ’63. Success is a wonderful thing, but it is very, very tiring.”

—George Martin

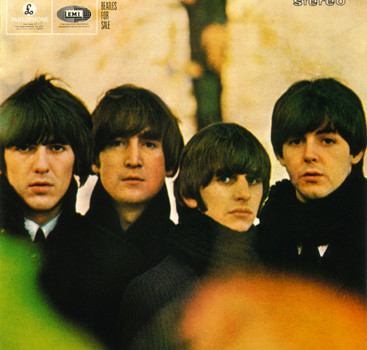

You can see the fatigue on the cover of Beatles for Sale. They look older and wiser. Instead of the Fab Four sitting on top of the world, these guys seem to be feeling the weight of it, as if global adulation were a burden. Put those four somber faces together with that title and the message is more cynical than playful. As the hottest property in the universe, with rigid recording deadlines to meet and exhausting tours to endure, the group is being packaged and sold to the nth degree. Still, they look great. There’s a Bohemian charisma about the cover image. You can imagine they have it in them to surprise the world, but surely not to amaze and even change it, which is what they would accomplish before the decade was over.

Fifty years ago they were in the EMI’s Abbey Road studios recording the album featuring the cover image of four “war-weary” musicians. Perhaps that’s one reason Beatles for Sale was never released in America, at least not until a 1987 CD. A butchered version (minus six songs) was packaged as Beatles ‘65, with a more conventional cover showing the group in various meant-to-be-cute-and-amusing poses. It didn’t matter to me one way or the other since I had them at my fingertips on the radio of the company car I was driving as a college traveler for W.W. Norton. I loved the music, singing along with it as I drove from campus to campus showing off the new Norton Anthologies in a ten-state swath from Alabama to North Dakota. I first heard “Eight Days a Week,” in downtown Memphis, “I Feel Fine,” on the car radio outside Little Rock, “She’s a Woman,” on a jukebox in Kansas City, and “Ticket to Ride” driving through the Badlands, windows down, spring blowing through.

I’d thought that traveling for a publisher would be a profitable way to satisfy my yen for the road, like commissioned vagabondage, but by the end of the first semester I was grinding through a miasma of motels and roadkill, nothing eventful happening until the day I arrived at the Chattanooga Tennessee Holiday Inn. Waiting for me, forwarded by the New York office, was a diseased-looking Indian airletter postmarked Udaipur that seemed to pulse and hum in my hand as I read the message inside, written on a leaky ballpoint by a British friend with a vivid prose style. He was describing a fascinatingly chaotic night journey on Indian Railways and urging me to join him. He concluded with this advisory: “Go with 10 pounds of luggage, 15,000 pounds peace of mind and the balance (say at least 100,000 tons) pure and indifferent love of humanity (a half ounce of tolerance will do here). Otherwise India will bring nothing but misery to you.”

Up to that moment I hadn’t been serious about going to India. I only knew that thanks to an expense account and the fact that each installment of my salary was being directly deposited, come summer I’d have saved enough to live for a year or more on the road. Due in great part to that letter, I turned down a job in the front office and got a ticket on the Queen Elizabeth, where I bunked with a guy from Liverpool who looked like John Lennon and had been exploiting the cult of the British invasion. One word from him in his Liverpool accent and American girls were swooning at his feet.

In Istanbul, after watching A Hard Day’s Night for the sixth time in a moviehouse near Taksim Square, I took an evening ferry across the Bosporus to Asia, caught a ride in a big truck and was on my way.

India Everywhere

There are times when memory blends so fluidly with experience that it becomes possible to imagine India beginning with the Beatles and continuing across Turkey to Tehran, to Kabul, to New Delhi with the Beatles singing “Every Little Thing” and “I’ll Follow the Sun” in a record store listening booth on the great Wheel of the Available called Connaught Circus.

Those two songs from Beatles for Sale rarely show up on lists of favorite Beatles tracks, but they’re in my top 20, if only because they blossomed in India. Paul was 16 when he wrote “I’ll Follow the Sun,” a perfect road song (“One day you’ll look to see I’ve gone, but tomorrow may rain, so I’ll follow the sun”) with as sweet a middle eight as anyone this side of Schubert could have composed. McCartney also wrote “Every Little Thing,” which may seem like just another “silly love song,” until you’re hearing John Lennon sing it in India.

Out of Reach

The other day I was thinking how different that year and a half on the other side of the world would have been if today’s communication devices had been available. At the heart of the whole experience was knowing that I was out of reach of my parents and everything to do with the routine reality of home or work life in the States. Looking back, I know a cell phone or iPad would have been good to have during the nine days I spent in a Katmandu fleabag reading The Sound and the Fury and experiencing Dostoevskian fevers as I fought off a mysterious virus. I could have texted my parents, thereby putting them in a panic with phone calls to the embassy for the immediate assistance of a trustworthy, preferably American doctor.

Fate Finds Me

Since my schedule was all over the place, the only way I could get mail was at Poste Restante in one city or another among the rough outline of my route I’d given my parents and friends (and agent). It was in Goa that the long arm of the homeland reached out and, most fatefully, found me. I was about to board an overnight train to Madras when a frantic postal clerk came running after me with a letter from my father in Indiana. I’d just checked for mail at Poste Restante in Panjim one last time and had been informed by this same clerk that nothing was there for Mr Stuart, no letters, it was impossible that anything had come. One of the unreal realities of the Indian experience lived in the gulf between the Possible and the Impossible. Now here was the postal clerk defying the impossible as he chased me down to personally deliver a message he assumed must be of supreme importance.

And he was right. Inside the envelope instead of the expected letter from my father was one to me at my home address from a girl I’d met in California some years before. My father’s note said “I enclose a letter from What’s-her-name in San Francisco.” That forwarded letter began the lively correspondence that led to a meeting the following summer in Venice, which led to an October 8 marriage to Miss “What’s-her-name.”

Narayan Meets the Beatles

Narayan Meets the Beatles

This past week, besides listening numerous times to “Every Little Thing,” “I’ll Follow the Sun,” and the other Lennon-McCartney songs on Beatles for Sale, I’ve been reading stories by the Indian writer R.K. Narayan, who creates characters not unlike the noble postal clerk in Goa who went out of his way for me that day. Reading Narayan and listening to the Beatles is like drinking good strong Indian chai in earthenware cups and eating scones with jam and clotted cream. Which is to say they are not mutually exclusive activities. Like the music of the Beatles, Narayan’s stories make you smile, lift your spirits, engage your sense of wonder, enrich your life, and infect you with a touch of the wanderlust.

The love-is-tough and life-is-hard songs on Beatles for Sale — such as “I’m a Loser,” “No Reply,” “Baby’s In Black,” “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party,” “What You’re Doing” — have equivalents in the stories of Narayan. One way or the other, every one of those songs is about thwarted love and embattled relationships, whether you’re a loser (“Of all the love I have won or have lost/There is one love I should never have crossed”) or your girl friend is cheating on you in “No Reply” (“I saw the lie, I saw the lie”), or if she’s left the party with someone else (“I wonder what went wrong, I’ve waited far too long, I think I’ll take a walk and look for her”).

Versions of these possibilities are in play in Narayan’s “The Shelter,” which begins with a man taking cover from a sudden heavy rain by ducking under a banyan tree. Soon he becomes aware of another person, oops, it’s his estranged wife. There they are, stuck together while the rain pours as only rain can in south India. The man tries to make conversation. He’s feeling awkward and she’s giving him nothing. As he natters on about rain and umbrellas and the coincidence of their meeting, she ignores him.

Married couples, especially those celebrating four decades or more together, will nod knowingly to read that Narayan’s couple “had had several crises in their years of married life. Every other hour they expressed differing views on everything under the sun …. Anything led to a breach between the partners for a number of days, to be followed by a reconciliation and an excessive friendliness.” Now that “the good rain” has “brought them together,” the man makes courtly overtures, and expects her to “be touched by his solicitude,” but she’s having none of it. He says he’s sorry, claims to be a changed man, tries to find out where she’s living, and finally says of the rain, “We have got to face it together,” to which she says “Not necessarily” and dashes off, disappearing into the downpour. Narayan’s hapless husband calls out to her, but it’s no use. Will he chase after her? Probably not. Of course if you’re sufficiently lucky or resilient or devoted, you’ll stay under the banyan tree, facing the rain together.