Michael Brown Was a Cardinal Fan — A Celebration of October Baseball

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

In spite of Thursday night’s season-ending loss to the Giants in San Francisco, St. Louis Cardinal fans enjoyed their share of baseball ecstasy in the 2014 post-season. With the glorious exception of Game One’s comeback win against Clayton Kershaw and the Dodgers, the manifestations of maximum ecstatic intensity happened at home, in Busch Stadium. At such times there’s nothing between you and almost 50,000 deliriously happy strangers but the television, and thanks to the HD flat screen, the sensation of being there is overwhelming — it’s you and your vastly extended Cardinal family, singles and couples, siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles and kids, all shapes and sizes. If you were really there, side by side cheering Redbird heroics, you’d be submerged in a delirious love-in, all high fives and hugs. But deep down you know that such cozy, familial thoughts are delusional, Missouri’s a red state and Busch a sea of red with the hometown crowd garbed in Cardinal colors. How many of these folks you’re jumping up and down with would stay friendly should the subject turn to something other than baseball, like for instance the shooting of a black youth by a white cop in a St. Louis suburb?

At first I had no reason to think the shooting of Michael Brown had anything to do with the team I’ve been following since I was a ten-year-old. The Cardinal heroes memorialized with images and statues in Busch Stadium include black players like Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Ozzie Smith. Interracial chemistry has been a key component of the Cardinals from the 1964 World Champions on through the championship teams of the 1980s. By the time the Redbirds surged into first place on their way to winning the Central Division, the Michael Brown story was all over the news, the shadow of Ferguson spreading in the direction of Cardinal Nation until a group of protestors, most of them African Americans, actually showed up outside Busch during the National League Division Series with the Dodgers. A chaotic scene developed when Cardinal supporters began yelling at the demonstrators. While some fans simply resented the inopportune intrusion, like how dare they rain on the Cardinal parade, others shouted racist cliches that were tame by Tea Party standards while one man sported a Cardinal jersey with the policeman’s name, Darren Wilson, taped on the back. At times it sounded like little more than opposing crowds at a high-school football game trading chants, “Let’s go Mike Brown!” vs “Let’s Go Cardinals!”

The Cap on the Casket

I wonder how many Cardinal fans affronted by the intrusion of racial conflict on the hallowed ground of playoff baseball knew that Michael Brown’s family had placed a St. Louis Cardinal hat on top of his coffin. Clearly the team had some personal significance for the Browns. Michael was shown wearing the hat in one of the photographs displayed next to the coffin and his father was wearing one during an interview. Various news stories also pictured people in the Ferguson crowds casually attired in Cardinal regalia, and there are fans among the Ferguson cops who show up at Busch wearing Cardinal jackets and hats, as viscerally devoted to the emblem of the redbirds on the slanted bat as the citizens of Ferguson rallying for justice in the name of Michael Brown.

Team logos are not to be taken lightly. Emerson suggests as much when he celebrates “the power of national emblems” in “The Poet,” where “the schools of poets and philosophers are not more intoxicated with their symbols, than the populace with theirs.” He mentions “stars, lilies, leopards, a crescent, a lion, an eagle,” and, why not, a pair of cardinals. In the ideal best-of-all-possible baseball worlds, the National Pastime prevails in a realm of its own, remote from the chaos outside the stadium. Of course there are skirmishes like the one in the first inning of the first game of the Division Series when Cardinals pitcher Adam Wainwright unintentionally hit Yasiel Puig of the Dodgers, the benches cleared, players roared and pushed at one another, and Wainwright escorted Puig to first base in friendly fashion, the two men briefly arm in arm, as if in respect of that pastoral world of highs and lows, wins and losses, where people who on the outside might blunder into deadly conflict cheer and cry together, are wounded and healed, brought down and uplifted, know joy and know sorrow, all within the precincts of the game.

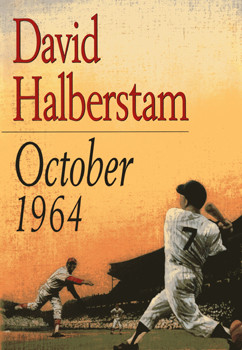

1964

Fifty years ago, on the last day of the 1964 season, the Cardinals completed one of the wildest runs in baseball history to win the pennant and the chance to face Mickey Mantle’s Yankees in the World Series. That feat seems all the more special and unlikely after my rereading of David Halberstam’s October 1964 (Villard 1994), which offers a fascinating back story for both teams. One of the elements that attracted Halberstam was the importance of the interracial makeup of the Cardinals in a year that had been charged with events more cathartic than the shooting of Michael Brown. In fact, the people in the New York office of W.W. Norton, the publisher I was working for, gave serious thought to the potential risk of driving a company car with New York plates in the Deep South only months after the murder of the three Civil Rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi. There was even some discussion about whether or not they could get me Mississippi plates. Halberstam, however, had no need to dwell on the climate of the times. Most readers, including baseball fans, knew what had been going on in the country during those explosive years.

“Where Are Our Black Players?”

In the course of showing how “more than most teams, the Cardinal players came to deal with race with a degree of maturity and honesty rarely seen in baseball at that time,” Halberstam writes about the onetime owner, beer baron August “Gussie” Busch, who was acutely aware that Budweiser sold more beer to blacks than any other brewery in the country. One day in the 1950s he asked his manager and coaches, “Where are our black players?” The all-too-obvious answer was, “We don’t have any,” to which Busch said, “How can it be the great American game if blacks can’t play?” And then: “Hell, we sell beer to everyone.” This burst of interracial enthusiasm roused the Cardinal scouts to action and by spring training 1964, a racially balanced championship team had been put together and harmoniously integrated. In the face of segregated living facilities, and Florida law, a wealthy friend of Busch’s bought a motel and rented space in an adjoining one, so that the entire team and their families could stay together. According to Halberstam, “a major highway ran right by the motel, and there, in an otherwise segregated Florida, locals and tourists alike could see the rarest of sights: white and black children swimming in the motel pool together, and white and black players, with their wives, at desegregated cookouts.”

Cardinal Serendipity

In the late summer of 1964 when I was in Norton’s New York office working out the itinerary for my tour of colleges from the Deep South to the Upper Midwest, I scheduled an October 15 visit to Creighton University in Omaha. I didn’t know at the time that Creighton was Bob Gibson’s alma mater. Nor did I have any reason to believe the Cardinals were going to catch up to and pass the fading Phillies in the pennant race. As long as I’d been rooting for the Cardinals, they’d never made it to the main event. I followed the Series as best I could, on motel TVs or on the car radio driving down through the Dakotas. On October 15 I landed on the Creighton campus where all anyone could talk about was Bob Gibson, Class of 1957, pitching the seventh game of the World Series (that’s him in action on the cover of October 1964). It had to be some kind of Cardinal serendipity, that on the day Gibson turned in one of gutsiest pitching performances in World Series history to win the deciding game of the 1964 Series, I was watching it on TV, cheering along with a crowd of cheering Creighton students. Somehow I found myself in the right place at the right time, a white guy in a suit feeling at home in baseball, sharing the ecstasy.