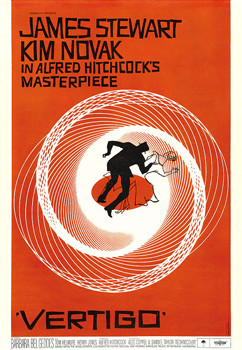

Poe’s Precipice of the Perverse: Hitchcock Takes the Plunge in “Vertigo”

By Stuart Mitchner

I suggest that Hitchcock belongs —and why classify him at all? — among such artists of anxiety as Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Poe. —François Truffaut

According to a 2012 critics poll in the British film journal, Sight and Sound, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) is “the greatest film ever made.” You can be sure that enlightened movie watchers around the world dispute that declaration, and with good reason. Even if I believed in the legitimacy of film rankings by “authorities” in the field, Vertigo would be nowhere near the top of my list. But when the late Robin Wood, whose writings on Hitchcock are classics of film criticism, demonstrates in eloquent and convincing detail why Vertigo is “one of the four or five most profound and beautiful films the cinema has given us,” I’m moved to reexamine my feelings about it, especially when a remastered print is available on DVD.

Having now seen the film twice in a three day period, I’m less appalled by the idea that people new to the medium or with limited knowledge of it will take the poll seriously enough to assume that Vertigo somehow sets the standard for film greatness. In the context of its era, it stands alone, a fascinating creation, ahead of its time, daring, inventive, and uncompromising. What sets it apart in addition to Hitchcock’s predictably masterful direction is Robert Burks’s cinematography, Bernard Herrmann’s score, and Jimmy Stewart’s performance as a man doomed to fall in love. Only Hitchcock could film a love story that takes the romantic metaphor to a morbid extreme. At the same time, as is frequently the case with Hitchcock, the picture suffers from the same lapses and excesses associated with the pop culture legend he crafted for himself as cinema’s rotund “Imp of the Perverse” — excesses he shares with the “Imp’s” author, that other morbid genius and master of the macabre, of whom Hitchcock has written: “… it’s because I liked Edgar Allan Poe’s stories so much that I began to make suspense films.”

Mad Love

Freely adapted from D’entre les morts, a lame thriller concocted by Thomas Narcejac and Pierre Boileau to catch Hitchcock’s attention, Vertigo is about a police detective named Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) who has retired from the force due to acrophobia brought on when he nearly falls to his death while pursuing a suspect. A college friend hires Ferguson to shadow his elegant, allegedly suicidal wife, Madeline (Kim Novak), who has been behaving strangely, brooding in cemeteries and communing with a museum portrait of her ghostly alter ego, Carlotta Valdes (a name that Poe would love). After saving her life when she jumps into San Francisco Bay, Ferguson falls in love with her and she with him, but when she jumped off the top of a Spanish mission bell tower to her death, he was unable to save her because of his fear of heights. The shock and the nightmares it engenders precipitate a nervous breakdown, from which he recovers with help from Midge, his former girlfriend who still loves him (a bespectacled Barbara Bel Geddes). When he meets Judy, a sales clerk without an elegant bone in her body (Kim Novak again) but with a haunting resemblance to Madeline, he’s compelled to make her over in the image of his dead beloved. This he accomplishes, only to discover that Judy had pretended to be Madeline as part of a plot involving the murder of the old friend’s rich wife. Twice deceived, taking Judy-as-Madeline back to the tower, he forces her to the top while chastising her for her duplicity and at the same time proving to himself that he can overcome his acrophobia. At the top, startled by the appearance of a nun, the girl falls to her death. Staring down at her body, Scottie Ferguson is “cured.” We know better. For Hollywood in 1958, this is a remarkably downbeat ending.

Jimmy Stewart

Of all the epigraphs that could be applied to Vertigo, the most apropos might be from Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale”: “I have been half in love with easeful Death/Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,” except that for Jimmy Stewart’s love-dazed Scottie, Death is beautiful and her name is Madeline. What Hitchcock ghoulishly classifies as a “necrophiliac” romance reaches its psycho-sexual pinnacle when the shopgirl Scottie has transformed into Madeline stands before him, “as if she were naked,” says Hitchcock, who consecrates the moment with a dizzying, full-circle 360-degree-angle shot of an embrace of Wagnerian proportions (to the Liebestod yet) between a madman and the corpse he’s created to satisfy his morbid lust (the level of discourse, again, typical of the master of the macabre). No one but an actor of Stewart’s stature, a star the moviegoing public absolutely believes in, could have preserved his integrity in so neurotic a role.

In the early scenes with Midge, in her apartment/studio (she’s an artist reduced to designing bra/lingerie ads), you have glimpses of the familiar “waal, shucks ma’am” Jimmy Stewart whom comedians and certain schoolboys in the 1950s loved to impersonate. The actor remains at a bland remove from the character until the moment he drags Kim Novak out of San Francisco Bay. It’s surprising that for all his attention to the virtues of the film, Robin Wood neglects to mention the extraordinary medium close-up two shot of Stewart and Novak after he’s pulled her out of the cold water. The image is on the screen only a matter of seconds, but in it you see the man coming face to face with his gorgeous fate for the first time. He’s shaking, out of breath, as he beholds, dazed, in a dream, the timeless beauty of the creature whose life he’s saved. An actor unsurpassed in believably and wrenchingly expressing extremes of anguish, Stewart makes you feel the man’s helpless plunge to the depths of his love for the unconscious woman in his arms; at this point his emotions are so exposed, it’s as if he thinks she’s about to die at the very moment he’s discovering and adoring her. All he can say is her name. It’s his first declaration of love. It also may be Novak’s most beautiful moment, for she’s seen in profile, drenched, damply radiant, like Hitchcock’s version of the Birth of Venus. We still haven’t heard her say a word, which is just as well since she never seems comfortable speaking the language of the wealthy woman she’s impersonating. While that serves the director’s purpose well enough, you still can’t help wishing a more accomplished actress were playing the part.

Wrong Move

Probably the most famous instance of Hitchcock’s fetish for women in spectacles is in Strangers On a Train, when the strangling of Farley Granger’s bespectacled wife is reflected in the lenses of her fallen glasses. Hitchcock makes Midge’s glasses her essential feature, a way of at once defining and deglamorizing her role as the sane, sensible, loving alternative to Scottie’s fatal fascination with Madeline and the portrait of Carlotta Valdes. Aware of the power of that image over the man she still loves, Midge uses a copy of the painting to compose what Robin Wood calls “a parody portrait of herself” as Carlotta, complete with her own dark-framed glasses, which look ridiculous in the elegant period trappings of the original portrait. Wood sees nothing to complain about in the cringe-inducing scene where Midge shows Scottie the portrait; he treats the embarrassment as if it makes filmic sense, as if she thinks she can render the obsession “ridiculous by satirizing it.” In fact, she humiliates herself, alienates Scottie by violating the image of his passion (he stalks out of the apartment), and worse yet, she violates the film’s credibility, having been forced by the Imp of the Perverse to make exactly the wrong move. When she tears her hair and berates herself (“Stupid! Stupid!”) she’s also voicing the sentiments of a large portion of the audience watching the irrepressible Hitchcock inflict a direct hit on his own creation.

Vertigo in the Perverse

All quibbling aside, I find the presence of Poe in Hitchcock appealing because it agrees with my sense of Hitch as a 20th century phenomenon in American culture comparable to Poe in the 19th century. Like Hitchcock, Poe inflicted perverse distortions on his own work, playing games, jesting, defying the logic of his creation with ornate, bombastic, melodramatic gambits of the sort that made T.S. Eliot observe that “The forms which his lively curiosity takes are those in which a pre-adolescent mentality delights,” and that inspired Henry James to call an enthusiasm for Poe “the mark of a decidedly primitive stage of reflection.” Comparing Poe to Baudelaire, his champion in France, James found him to be “much the greater charlatan of the two, as well as the greater genius.”

Finally, it’s worth noting the employment of vertigo as a metaphor in “The Imp of the Perverse” where Poe writes, “We stand upon the brink of a precipice. We peer into the abyss — we grow sick and dizzy. Our first impulse is to shrink from the danger. Unaccountably we remain.” The notion of the perverse, of knowingly surrendering to the fatal impulse, is developed at length in the same long paragraph as Poe elaborates on this moment on the brink, as if one were tempted by curiosity to experience “the sweeping precipitancy of a fall from such a height … for the very reason that it involves … the most ghastly and loathsome images of death and suffering which have ever presented themselves to our imagination — for this very cause do we now the most vividly desire it. And because our reason violently deters us from the brink, therefore do we the most impetuously approach it. There is no passion in nature so demoniacally impatient, as that of him who, shuddering upon the edge of a precipice, thus meditates a Plunge.”

In a 1960 article called “Why I Am Afraid of the Dark”, Hitchcock recounts his discovery of Poe. “When I came home from the office where I worked I went straight to my room, took the cheap edition of his Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, and began to read. I still remember my feelings when I finished ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue.’ I was afraid, but this fear made me discover something I’ve never forgotten since: fear, you see, is an emotion people like to feel when they know they’re safe.”

As always, I found Hitchcock’s most interesting remarks in François Truffaut’s collection of interviews, from which several quotes are taken, including the one at the top.