“The Soul of All of Us Together” — Scheide, Schubert, Bach, and the Dance of the Organist

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Once you reach a certain age, your catalogue of associations is so extensive and so many-sided that it’s possible to discover a personal connection to virtually any worthy subject that comes your way. Sometimes the connection is too tenuous or too far-fetched to pursue. Concerning medieval manuscripts, pipe organs, Bach, and William Sheide, who died November 14 and was recently remembered in a memorial service at Nassau Presbyterian Church, the connection with my father, an organist who studied Medieval manuscripts and requested that Bach be played at his funeral, is right there. So, in particular, is the reference to the acquiring of the Bartholomaeus Anglicus (1472) in Fifty Years of Collecting (2004), the Princeton University Library’s 90th birthday tribute to Scheide, the renowned bibliophile, benefactor, musician, founder of the Bach Society, and Princeton University graduate (Class of 1936). For some 20 years, until his eyes gave out, my father studied, edited, and for all purposes lived in Bartholomaeus Anglicus, De Proprietatibus Rerum, which dates from the same period.

In one of the essays in Fifty Years of Collecting, Louise Scheide Marshall recalls growing up “surrounded by books of all sorts, sizes, and ages.” She remembers how eager her father was to show her “a special book or two,” one of her favorites being a calligraphic manuscript of Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott bound in “lush blue morocco with inset opals.” She also admits to having “a special love for illuminated manuscripts,” and a love for “the sound and touch of the vellum.” Me, I grew up to the sound of my mother heroically typing my father’s 240-page heavily footnoted and annotated doctoral dissertation on the aforesaid De Proprietatibus Rerum.

In the Presence

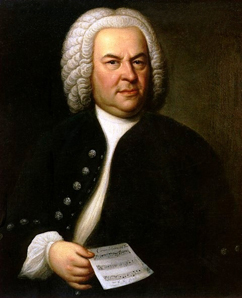

Three years ago I found myself in the presence of William Scheide’s Bach. Painted in 1748, the Haussmann portrait is one of only two that the composer sat for in his lifetime; it hangs near the entrance to the living room of the Scheide home on Library Place. The day I was there on a magazine assignment, Mr. Scheide was seated with his wife Judith by his side. A massive Holtkamp pipe organ loomed at the far end of the room; perched within reaching distance of the keyboard, was a stuffed animal I recognized from a decade of bedtime-story-reading as Curious George. His owner’s impish smile left no doubt that this was a man who had room in his life for both the mischievous monkey and the intimidating presence in the portrait — not to mention Dennis the Menace, judging from what his children said during the memorial service. And although his fondness for word play was noted, it seems that he was, like my father, “a strict grammarian.”

After some conversation, most of it about the logistics of installing and maintaining the Holtkamp, Bill Scheide was induced by our photographer to “play something” on the magnificent object. Although I had a notebook and pencil in hand during the brief demonstration, I wrote nothing down and have no idea what he played — but it had to have been Bach. The magnitude of the sound prompted a memory of my father’s prize possession, a pipe organ a third the size of the mighty Holtkamp but no less capable of raising the roof. And of course the roof-raiser of choice was Bach.

Schubert’s Adagio

While Bach also dominates the memorial service planned two decades ago by Scheide himself, the program is structured around Schubert’s Quintet in C Major, which was created a few months before the composer’s death at 31 in November 1828. As soon as I saw the Town Topics reference to Scheide’s son John’s thanking the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra Chamber Players after the performance of “a movement from a string quintet by Schubert,” I knew it had to be the adagio that Arthur Rubinstein called the “entrance to Heaven.” In a biographical film, The Love of Life, the world-famous pianist struggles to express the depth of his feeling for Schubert’s adagio. “This is something that I love more than anything …. It might be the soul of humanity,” he says, making a slow sweeping gesture with one hand, “the soul of all of us together.”

Rubinstein is referring in particular to the opening measures where Schubert seems to have ventured into some region between worlds known and unknown, life and death. At this moment, about halfway through the movement, the music intensifies, suggesting a struggle, desperate, passionate, and abruptly resolved before returning to the mood of mystery and longing and wonder with which it began.

That day in 2011, at the house on Library Place, Judith Scheide said the first thing her husband asks for in the morning is music. “We usually begin with Schubert,” she said. “Bill loves Schubert. It centers him for the day.”

The Organist’s Dance

When Judith Scheide said the day began with Schubert, not Bach, I was pleasantly surprised. The depth of Scheide’s devotion to Bach is evident in the choices he made for the memorial service. If the “day” of the service began and ended with Schubert, the eventful essence of it was Bach.

During my amateur listener’s tour of great composers, I’ve steered clear of Bach, perhaps because I’m waiting for an excuse — some anniversary coincidence — to take the plunge. If there’s any one obvious explanation for why I may have shied away from the subject, it’s that Bach’s music is associated with my father’s death. The organist at St. Paul’s in Key West for whom he sometimes covered knew exactly what to play for the funeral service and Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor was at the top of the list.

Taking advantage of an excuse to finally explore Bach, I looked online for performances of the numerous pieces listed in the Scheide memorial service program. Out of the lot the one that held me was “Alle Menschen müssen sterben,” BWV 643 (“All Mortals Must Die”), as performed on a Fratelli Ruffati pipe organ by T. Ernest Nichols, a student of Virgil Fox. The video was filmed in a chapel at Olivet Nazarene University in Bourbonnais, Illinois. What kept me going back to it again and again was the feeling that I was discovering how it would have been to stand behind my father as he played during the years when he was the regular church organist. Never a willing churchgoer, I always took his playing for granted, instead of proudly thinking how great that my austere father was producing the thunder that made the building shake. Perhaps it was because I was too far away. I couldn’t see his hands, only his face. Now and then he would look down at something, as if distracted.

Like my father, Nichols is slightly built, greyhaired, bespectacled, so here I am looking over his shoulder, in effect, for the first time, and now I know why he kept peering down. I always assumed the organ had only a few pedals, like the piano, not this array of wooden shafts, the equivalent of another keyboard to be played with the feet. It’s embarrassing to realize that I was as clueless and benighted about his music as I was about his scholarship. Funny, while his hands know right where to go, his feet are all over the place, he’s walking here, there, stepping this way, that way, his feet sometimes well apart only to slide side by side until they seem to be riding the same pedal; it’s like a slow thoughtful dance with comical overtones, the way the right foot suddenly shoots up to hit one of the higher pedals, a Charlie Chaplin move, like when he skates going around a corner, one leg out, a touch of slapstick for sure, but all the while the music being made is simple, lovely, consoling, perfect, and knows exactly where it needs to go.

And then at the end comes a sweet surprise, that playful little rolling repeat of the sad figure that’s been like a gentle chant all through, it feels improvised, as if the stern man in the portrait was smiling in spite of himself.

Note: In my Feb. 7, 2007, column on Schubert (“A Little Book Leads the Way: Celebrating Schubert’s Birthday”), I suggested that Toscanini once said that the music he wanted to hear as he died was the adagio of the String Quintet in C major. Apparently, that was not Toscanini’s request but Rubinstein’s, as he admits in the film “The Love of Life.” That was my error, though I would not be surprised if Toscanini had to pick a specific piece of music to hear on the way out, the adagio would be high on the list, if not at the top.