Thoughts On Martin Luther King In Shirtsleeves and an Unforgettable Film

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

This being a week after the national holiday devoted to the man who gave his heart, soul, and life to the cause of racial justice, I’ve been reading The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, edited by Clayborne Carson and published in 1998 by IPM Warner. With the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X coming up next month, I’m also reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X, written with Alex Haley and published in 1968 by Grove Press. In addition, thanks to TCM’s special MLK birthday programming, and Comcast On Demand, I’ve been able to see One Potato, Two Potato (1964), an unforgettable yet sadly all but forgotten film about racism in the midwest.

Getting Physical

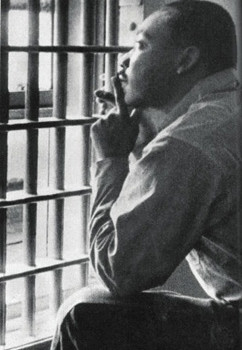

For me, the most striking photograph in King’s autobiography is the full-page medium-close-up of him taken staring through the bars of his cell the Birmingham jail in October 1967, half a year before his death. He’s seen from the side, his chin propped in the “V” formed by his thumb and index finger, the other hand holding one of the bars. He appears to be in casual attire, workingman’s shirtsleeves and trousers, a notable departure for a man most often seen in suit and tie, arm in arm with colleagues or supporters at an event or declaiming at the pulpit. The preacher and public speaker, perennial leader of Civil Rights gatherings, usually looks a bit buttoned-up, which makes it that much more dramatic the moment that voice comes thrillingly forth. When he belts out his stirring “I have a dream” mantra, it’s hard to believe such oratorical ecstasy is coming from the man in the well-tailored suit. The grainy, close-to-soft-focus quality of the prison photograph gives an aura of mystery to the pose, as if the index finger of his left hand might be sending a subtle signal to his followers, a calming “Ssh, hush now,” that contrasts with the presence of latent, virile force and great physical strength, like that of a star player about to charge onto the field or the court or the diamond or the stage.

No wonder, then, that the first chapter of his book presents him as a newborn exemplar of physical and mental health: “From the very beginning I was an extraordinarily healthy child. It is said that at my birth the doctors pronounced me a one hundred percent perfect child, from a physical point of view. I hardly know how an ill moment feels.” The same thing would apply, he says, to his “mental life,” that he has “always been somewhat precocious, both physically and mentally. So it seems that from a hereditary point of view, nature was very kind to me.”

As for his homelife, it was also “very congenial. I have a marvelous mother and father. I can hardly remember a time that they ever argued … or had any great falling out. … It is quite easy for me to think of a God of love mainly because I grew up in a family where love was central and where lovely relationships were ever present. It is quite easy for me to think of the universe as basically friendly mainly because of my uplifting hereditary and environmental circumstances. It is quite easy for me to lean more toward optimism than pessimism about human nature mainly because of my childhood experiences.”

In Contrast

King’s emphasis on a happy, healthy, loving “quite easy” upbringing shines a light on the world of difference between the lot he was born into and the one that was Malcolm Little’s. The first chapter of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, titled “Nightmare,” begins with his pregnant mother watching as torch-bearing, shotgun-brandishing Klansmen surround the house on horseback shouting for her husband to come out before proceeding to smash all the windows with their gun butts. That was in Omaha, Nebraska. Three years later in Lansing, Michigan, six-year-old Malcolm’s activist father was beaten to death and “laid across some tracks for a streetcar to run over him.” From that horror forward it’s one blow after another, the insurance company refusing to pay (claiming the murder was a suicide), the forces of welfare applying pressure rather than helping, the mother finding and losing another man, then going mad, the family shattered, Malcolm taken in by caring foster parents, doing well in school, only to be told by one of his teachers that he has no future as a lawyer or a teacher in that community even though he has shown himself to be academically superior to white students.

Right now I’m 100 pages into the Autobiography and can’t put it down. I can’t believe it’s taken me this long to get around to what is clearly one of the major books of the sixties. I hope to write more about it next month.

Brave and Brilliant

One Potato, Two Potato is a deceptively “small” film about an interracial couple living in what seems to be a relatively enlightened, reasonably tolerant northern Ohio town. Next to 1967’s overblown, Oscar-sweeping, hamhandedly politically correct Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Larry Peerce’s picture is both brave and brilliant, a landmark work, as human and powerful as Stanley Kramer’s blockbuster is hollow and belabored. Although One Potato, Two Potato received only one Oscar nomination (for Orville Hampton and Raphael Hayes’s’ original screenplay), it caused a stir at Cannes, winning the Best Actress award for Barbara Barrie and leaving those in the audience in stunned silence before they erupted with what Time magazine called “the longest, loudest ovation in nine years.”

To make a tasteful film on a taboo subject in a year where racial intermarriage was still illegal in 14 states would already be a noteworthy accomplishment, but there are scenes of such searing truth in One Potato, Two Potato that it’s hard to imagine them ever being surpassed or even equalled. The film works from the outset because the couple is believable, both as individuals and as partners in the relationship. Bernie Hamilton’s Frank is a long way, thankfully, from the handsome, accomplished, too-good-to-be-true character played by Sidney Poitier in Dinner. He’s not handsome, not ugly, just what you’d call a “regular guy” and is treated as such by his white co-workers. He’s introduced to Julie by his friends, a white couple. If you’ve seen Barbara Barrie as Dennis Christopher’s mother in the feel-good favorite Breaking Away (1979), you know how well-cast she is as a shy, pretty, thoughtful divorcee raising a little girl by herself in the four years since her husband (Richard Mulligan) walked out. What begins as a friendship never quite becomes a fullblown romance. Julie and Frank share a playful sense of humor, taking part in a spontaneous game of hop scotch in the town park at night (a reflection of the child’s game for which the film is titled) and a foot race that leads to their first and only kiss, an astonishing moment to imagine appearing on American movie screens in 1964 (no surprise, the film ran into serious distribution difficulties).

One of the most telling sequences comes when the ex-husband shows up at the house where the couple and the child have moved in with Frank’s parents. When he sees his five-year-old daughter playing in the front yard he’s instantly smitten. In a lesser film he would be the stereotypical mean-spirited, irresponsible father who abandoned her and is scheming to lure her away. While it’s true that he’s brought her a gift, a huge stuffed animal, the games he plays with her (she has a toy gun, he lets her shoot him dead, they face off in a show-down) seem spontaneous, without any ulterior motive other than the perfectly human one of wanting her to like him. It’s the opposite of what you’d expect in a flashback narrative framed by a grim court hearing over custody of the child. Thanks to Robert Mulligan’s performance, you feel for him, he’s so clearly taken with the little girl he hasn’t seen since she was an infant. When Julie comes out of the house to speak with him, he still apparently has no intention of taking the child away from her. But the instant he sees the black husband and his black parents everything changes. It’s a shocking, deeply ugly moment of truth, he’s truly horrified, and the audience finds itself facing, head-on, naked racism. It’s chillingly real, purely animal, not hatred, but an absolute of fear and disgust revealing a level of twisted, soul-sickness it’s disturbing to witness. He can’t speak. He has to turn away, sickened and afraid, really as if he were confronted with monsters who have his blond wife and his lovely little blond daughter in their clutches.

Several scenes that follow are no less powerful — Julie physically attacking Frank when the judge rules against them, the child hitting her mother in rage and confusion when she realizes this stranger she played with one afternoon is taking her away from her home, her mother and adoptive father, her baby brother, her grandparents. Why is she being punished, she asks. What did she do wrong?

The grim truth of the judge’s verdict in favor of the white father, which he realizes is morally skewed, allows that the child has a better chance in life with a single white parent than in a mixed-race family. However pained by it Dr. King himself might have been, he would understand all too well the judge’s terrible rationale.

His Link to Life

There is no mercy, no hope, no bright light in the ending of One Potato, Two Potato, only that devastating last image of a screaming sobbing heartbroken child who thinks that she’s being driven away from her happy home life because she did something wrong.

Again, think of Martin Luther King’s words about his birth and loving upbringing, his “marveous” parents and his mother Alberta Williams King, who “has been behind the scene setting forth those motherly cares, the lack of which leaves a missing link in life.” It’s interesting that the one time in the book when King takes off the coat and tie and lets his hair down is in a letter to his mother written in October 1948 when he was 19 going on 20. There, after telling her how he boasts to the boys at Crozier Seminary that he has “the best mother in the world,” he refers to a girl he “used to date” and has “been to see twice,” and then tells his mother, “I met a fine chick in Phila who has gone wild over the old boy.” At a point in his life when he’s reading Thoreau on civil disobedience, Marx on capitalism, Nietzche on the power of the will, and discovering Gandhi on passive resistance, King is writing to his mother about a “fine chick” and boasting of how “the girls are running me down” (as in chasing him). What’s particularly revealing about the letter is how open and easygoing his relationship with his mother seems. He can talk to her comfortably, as to a close friend, because, as he puts it earlier, she instilled in him “a sense of ‘somebodiness’ “ and then said “the words that almost every Negro hears before he can yet understand the injustice that makes them necessary: ‘You are as good as anyone.’ “