In the Month of Jazz and Black History — Clark Terry and Malcolm X

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Clark Terry (1920-2015), whose horn could charm the birds off the trees, was adept at translating the lyric of a song into what he called the language of jazz, “how to bend a note, slur it, ghost it, how to say ‘I love you’ to a lovely lady.” Terry had what critic Gary Giddins called “comic esprit” — “every note robust, beaming, and shadowed with impish resolve and irony.”

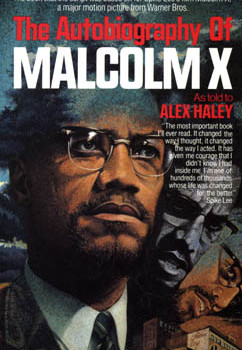

It’s fitting that news of the death of a great jazz musician has surfaced in the last week of Black History Month, which also happens to be, for obvious reasons, Jazz Appreciation Month. The music some call “the sound of surprise” also plays a part in The Autobiography of Malcolm X (as told to Alex Haley), most compellingly in the book’s vivid account of the dance hall scene in wartime Harlem. Black history and jazz history came together again when Clark Terry died on February 21, exactly 50 years to the day Malcolm X met a violent end in a Harlem ballroom.

Clark was There

“I was known to almost every popular Negro musician around New York in 1944-45,” says Malcolm X, who once hung out at the Savoy Ballroom and the Apollo Theatre, most often with members of Lionel Hampton’s band. According to his biography Clark (2011), Terry was in the trumpet section of Hampton’s band around the same time and soon after played at the Apollo with Illinois Jacquet. His account of the time has the feel of similar passages in the Autobiography: “I felt the beat of Harlem, the soul of black, brown, and beige America …. We played a few hot swinging tunes that night …. The audience was on their feet!”

Anyone intrigued by the scene brewing in New York in the swing to bop era of the war years will find one of the richest accounts of the period in Malcolm X’s book. While it’s understood that he’s on his way to salvation (and betrayal and death) with Elijah Muhammad and the Church of Islam, he clearly enjoys recounting his years as a hustler and petty thief and provider of reefer highs to jazz musicians whose names he also clearly enjoys dropping. If the right person had been around when he was growing up in Lansing, Michigan — say a teacher as generous as Clark Terry was known to be — Malcolm’s mission in life might have been music.

The Film

Thanks in part to the media fallout around Sunday’s Academy Awards, I watched the DVD of Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X, for which Denzel Washington received a Best Actor Oscar nomination. Besides comparing film and book, I was curious to see if Lee did anything with the anecdote about 13-year-old Malcolm Little’s short-lived career as a boxer, which is where I connected with and committed to the narrative. That Lee would bypass Malcolm’s misadventures in the ring is understandable, but the exclusion is related to the fact that the film begins with young Malcolm already enjoying life as a zoot-suited free spirit in Boston. By going with that structure, Lee consigns Malcolm’s traumatic, pivotal years growing up in the midwest to a series of flashbacks, which inevitably lessens the impact of the teen-ager’s escape to urban excitement from a middle American past marked by Klansmen firebombing his house and murdering his father and the definitive realization that the only future possible for him was a life of menial labor.

The Boxer

My encounter with the Autobiography coincided with a reading of the letters and speeches of Lincoln for last week’s column. One quality the two leaders have in common is self-deprecating candor of the sort found in Malcolm X’s account of adolescent humiliation in the boxing ring, the scene that Spike Lee chose to ignore. While I’ve been unable to find any quotes from Lincoln on his time as a wrestler who reportedly lost only one match out of 300, it would be in character for “honest Abe” to offset his prowess, perhaps by talking about the one match he lost.

While the incident has been framed by Haley, who introduces it with reference to the jubilation “among Negroes everywhere” when Joe Louis became the heavyweight world champion by knocking out James J. Braddock, Malcolm X’s voice comes through loud and clear as he recalls his first fight, with a white boy named Bill Peterson: “Then the bell rang and we came out of our corners. I knew I was scared, but I didn’t know, as Bill Peterson told me later on, that he was scared of me, too. He was so scared I was going to hurt him that he knocked me down fifty times if he did once.”

The defeat took a toll on the 13-year-old’s reputation (“I practically went into hiding”): “A Negro just can’t be whipped by somebody white and return with his head up to the neighborhood …. When I did show my face again, the Negroes I knew rode me so badly I knew I had to do something …. I went back to the gym, and I trained — hard. I beat bags and skipped rope and grunted and sweated all over the place. And finally I signed up to fight Bill Peterson again.” In the standard Hollywood scenario the training would pay off, but “the moment the bell rang, I saw a fist, then the canvas coming up, and ten seconds later the referee was saying ‘Ten!’ over me …. That white boy was the beginning and the end of my fight career.”

Only at this point does the Muslim activist of the present intrude, declaring, “it was Allah’s work to stop me: I might have wound up punchy.”

Turning Point

One of the most devastating moments in the Autobiography (“the first major turning point of my life”) is delivered by a sympathetic teacher who tells a boy who was chosen class president that his superior academic performance will be of no use to him if he hopes to be a lawyer or a teacher. “One of life’s first needs,” the teacher tells him, “is to be realistic about being a nigger” and “a lawyer is no realistic goal for a nigger.” The white students whose grades were no match for his had been encouraged to become whatever they wanted while Malcolm, being “good with his hands,” was encouraged to be a carpenter.

“It was then,” Malcolm writes, “that I began to change — inside.”

The casual use of the n-word no longer “slipped off his back,” he stared at classmates who used it, “drew away from white people,” answered only when called upon, and found it “a physical strain simply to sit” in that teacher’s class. The “very week” he finished the eighth grade, he boarded the bus for Boston and his destiny.

Pure Breathtaking Cinema

There is, thankfully, nothing in the prose style of the Autobiography comparable to the bravura shot in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X that the director and his cinematographer Ernest Dickerson must have been proud of, and rightfully so; for pure breathtaking cinema, nothing else in the film comes close to it.

The equivalent moment is in the book’s opening chapter. After a team of mounted Klansmen terrify Malcolm’s family and his pregnant mother (she’s pregnant with him), they ride “into the night, their torches flaring, as suddenly as they had come.”

In the film they ride into an immense luminous storybook moon, each rider equidistant from the other, as if they had been posed in place for the shot. All the fearful immediacy of their galloping shouting torch-waving window-shattering presence has been redefined into “something rich and strange” with a flick of the directorial wand. In 2015 viewers might assume some form of digital enhancement has been put spectacularly into play, so perfect is the effect of the tiny figures silhouetted against a moon as big as Mt. Everest and as luminous as some mad genius’s fantasy of the godhead. There it is, you gape in wonder, then it’s gone and you’re thinking “what’s a piece of visual poetry like that doing in a place like this?” We’ve just witnessed Klan terrorism in a film about the black leader who became famous chastising the “white devils,” and the coda to that episode of racist viciousness is — a thing of beauty?

Writers are taught to “kill your darlings.” If a phrase or a metaphor makes you pat yourself on the back, chances are it’s something you want to look at very carefully the next morning. Graham Greene termed the tracking of suspect figures of speech “shooting tigers.” But really, why in the name of contextual decorum deprive the audience of an image so stunning? How to justify leaving a piece of perfect cinema on the cutting room floor? Still and all, it feels wrong — a bit like showing John Wilkes Booth galloping away from Ford Theatre into a moonlit dreamscape.

Clark Terry

Better to end with one of Clark Terry’s “darlings.” Describing the way Duke Ellington handled his musicians (“all these very different attitudes and egotudes”), Terry writes, “He knew exactly how to use each man’s sound to create the most amazing voicings. The sounds of trains, whistles, birds, footsteps, climaxes, cries. Rhythms that vibrated the floor. Harmonies with ebbs and flows that almost lifted me right out of my chair.” Terry imagines the eyes of the audience “glued to us like we were the fountain of life. The music was so powerful and electric, if I’d had a big plug I could have stuck it in the air and lit up the whole world.”

———

The passages from Clark’s lively memoir were also quoted in my review. “The Time of His Life: Reading Between Clark Terry’s Lines,” Town Topics, Feb. 15, 2012.