“Where Do We Go From Here?” — Thoughts on Diaries, George Kennan, and the Demise of a Building

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Whenever I see the snow-covered ruins of the former medical center I’m reminded of the euphoria of the day I became a father and of the trauma of enduring an all-night ER vigil in July 1997 shortly after my son turned 21. It’s also impossible to drive by the site without thinking of two of Princeton’s most illustrious residents: Albert Einstein, who died in the hospital in April 1955, and George Kennan, who died ten years ago on the 17th of this month at home on Hodge Road. On both occasions, Princeton was datelined around the world.

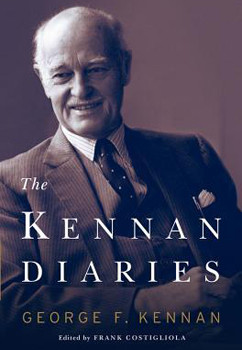

Thoughts of George Kennan evoke memories of Princeton during the first six years of the 1980s when my wife, son, and I lived in a garage apartment on the “ample grounds” behind “the sturdy, spacious turn-of-the-century structure” described in Kennan’s Memoirs 1950-1963. When he returns to the house in August 1953 after the tumultuous period during which he served as U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, he finds the place, as recounted in The Kennan Diaries (Norton 2014), “in dismal shape: empty, battered, barn-like, electricity and telephone shut off, the yard neglected and unkempt,” poison ivy growing all along the drive, and “a family of cats” living in the garage, above which my cat-loving family would live some 30 years later. In the necessarily more circumspect and polished Memoirs, 146 Hodge Road is the “comfortable, reliable and pleasant shelter” George Kennan and his wife Annelise would inhabit for five decades. While being “devoid of ghosts and sinister corners,” the house was “friendly and receptive in a relaxed way, but slightly detached, like a hostess to a casual guest, as though it did not expect us to stay forever.”

Kennan’s Tower

When the former Kennan home was on the market a few years ago, my wife and I returned to it for the first time since trick or treat visits with our son in the late 1980s. My objective was to see the tower study where GK (as I refer to him in my own journal) had done so much of his writing. I used to imagine him up there communing with Chekhov, warmed by the wood-burning stove he would feed with firewood he chopped himself. From Kennan’s tower I looked down at the windows of the garage apartment and the ground-floor room that had been my study, remembering how at night I would often gaze up at the lighted window when he was at work. Since I was busy writing a novel under contract, it was a way of keeping company.

In fact, there’s a passage in the Diaries that writers everywhere would do well to memorize. On September 4, 1951, George Kennan’s only message to himself after “a thoroughly wasted summer” is “Write, you bastard, write. Write desperately, frantically, under pressure from yourself, while God still gives you the time. Write until your eyes are glazed, until you have writer’s cramp, until you fall from your chair for weariness. Only by agitating your pen will you ever press out of your indifferent mind and ailing frame anything of any value to yourself or anyone else. Think neither of rest, nor relaxation, nor health, nor sympathy. These things are not for you.”

He held to his mission, writing just under 20 books, winning two Pulitzer prizes and two National Book awards.

On the Bench

While I’d never had the nerve to ask Kennan if I could see his tower study, my irrepressible six-year-old son wasted no time in charming a personal tour out of our landlord. My journal includes several encounters between the two, for instance, May 24, 1983, when GK came over for a chat before he and Annelise left for Europe. While we talked, my son, a first grader at the time, was sitting between us on the bench in front of the carriage house that was our home. Kennan had painted it rust-red with green trim (“Norwegian style,” he told us) to match the miniature replica opposite, a playhouse he’d built for his own children. The author of American Diplomacy was talking about his attempt to develop something better than the standard foreign service prose for the famous “X article” when the boy on the bench suddenly began discoursing on the subject of codes. According to my journal, “GK patted him nicely but firmly on the head and said ‘Let me finish, Benjy,’” while continuing to cheer me up by relating some of his own experiences with clueless editors (my novel was published that October, the first copy hand-delivered to me by a smiling Annelise, who had intercepted the UPS man).

Star Wars and Cookies

Two sides of life behind the Kennans are on view in my entry from Dec. 17, 1985: “Walked out to get the empty trash can and GK was sweeping the driveway where the bricks slope down to the street. We started talking about the Star Wars madness. He told me it was [Edward] Teller’s idea, that he had talked Reagan into it. ‘He’s been trying to start a war between the U.S. and the Soviets for years and now it looks as though he may succeed!’

“While I was writing this, the phone rang, and it was Annelise. She was coming over with some cookies she’d baked. I went out to meet her — the first snow of the winter was falling. I walk her back to our house. She has brought us wine, too. She comes in. Leslie is already ready for bed, Ben is watching a Christmas cartoon special, this journal is lying open on the floor of the living room. She is remarkably nice, this woman who at first view intimidated us (back in the summer of 1980). But now she has real fondness for us (especially Leslie whom she hugged and called “sweetie”) and we for them both.”

For a change in tone, there was the time during a heavy snow later that same winter when a taxi carrying Leslie home couldn’t find the driveway. After the driver dropped her off: “We look out the window and there’s the taxi — on the Kennan’s lawn! I mean all the way down by the patio! He’d driven right over the flower beds! About an hour later our distinguished landlord is on the phone booming, ‘Stuart! What happened to the lawn? Somebody’s been driving all over the lawn!’”

Facing 80

The winter of 1985-86, George Kennan was approaching his 82nd birthday. He’d been anticipating the big number in a September 3 1983 entry from the Diaries: “I shall soon be 80 years old. I am not in good health. My days are narrowly numbered …. In my personal life I see nothing but grievous problems and dangers on every hand …. At the same time, I am impressed and humbled by what, as I am constantly being reminded, my name, and the image they have of me, have come to mean for many thousands of people.” He goes on to observe that “if, in these final years, there is little I can achieve by doing, there is still something to be achieved by acting creditably the part in which fortune has cast me … to try to look, at least, like what people believe me to be … and, by doing this, to try to add just a little bit to their hope and strength and confidence in life.”

I realize now that he was “doing this” every time he spoke with us, whether he was identifying the skink “Benjy” had found and held out for his inspection, or talking with me about writers and agents. According to the Diaries, in August 1983 Kennan was suffering from a kidney stone that “gnaws and hurts” and will become life-threatening the following year. In my journal from November 1984, I note how worried we’d been (“feeling in these past weeks as if a close relative were in danger”): “Things did not go well and Annelise says he’d had pneumonia and that they might have to operate.” By Thanksgiving we were relieved to hear the laser surgery in New York had worked and he was home and healing: “Today he was outside and we talked. He is going to be at the house and ‘idle’ (for him) for some time, which means, he said, we would have time to talk.” Meanwhile my wife had baked a Russian coffee cake that she and Ben had taken over to the Kennans. In early December, I record this exchange: “GK: ‘When I got home from the hospital I was about ¼ myself. Now I’m feeling about ¾ myself.’ Me: ‘That’s about as much as most people ever feel isn’t it?’” Seeing how exhausted I was (about ½ myself) after a typical day keeping up with my son, he tells me, “You’ll make it.” We agree that Ben at 8 is “sometimes over 100 percent himself.”

Long Lone Walks

In the November 15 1989 entry of Diaries, after the Berlin Wall had been brought down (“by the power of an entourage that wants performers more than it wants scholars”), which led to a deluge of “requests for interviews, TV appearances, articles, statements,” he asks “Where, then, do we go from here?” Where he goes is for a “long lone walk through the empty nocturnal Princeton streets, trying to think out the answer to that question.” This image of Kennan walking at night moves me but at the same time makes me smile because a more familiar image has the sage of Hodge Road seated tall in the saddle of a bicycle pedaling on his way to and from his office at the Institute for Adanced Study.

One Last Thought

When the hospital was undergoing the grotesque process of deconstruction, it was hard to remember personal moments, like watching my wife give birth, holding my son seconds after he was delivered, and seeing him through a serious operation at nine months and life-saving surgery at 27, on either side of the ER crisis of July 1997, from which we continue to feel the aftershocks. But nothing will ever diminish that time of happiness, April 28, 1976, in a room in a building that is no more, sitting on the bed with wife and newborn baby, and, as George Kennan describes a perfect moment in his student days at Princeton, “all was complete.”

Previous backyard views of the Kennan’s are in the review of John Gaddis’s Life (Nov. 23, 2011), a column on two Princeton streets (July 19, 2006), and one on the occasion of Kennan’s 100th birthday (Feb. 18, 2004). These can be accessed at www.towntopics.com/backiss.html.