Poetry’s Month Begins With “Mad Men,” Wallace Stevens, and Tomas Tranströmer

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

One of my favorite moments in Mad Men, maybe my all time favorite, is when the craven Pete Campbell (Vincent Kartheiser) thinks he has the goods on Don Draper (Jon Hamm). He’s got proof that the genius who landed the Lucky Strike account for Sterling Cooper is a fraud, a man with a sleazy past and a stolen identity, so the two of them, the self-righteous loser and the handsome mystery man, march into the shoeless boss’s office where Pete smugly delivers the awful truth to little Bert Cooper. In a moment Robert Morse was born to play, Bert stares at Pete with the mother of all withering looks and says, “Whoooo cares?” Twice. And he doesn’t just say it, he leans forward and croons it, packing his total disregard of conventional small-minded morality into those two words.

My wife and I will go back to Mad Men next Sunday for the first time since we gave up after losing patience and moving on to the more compellingly plotted pleasures of Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones.

You may wonder why a column planned for the first day of April begins with a recollection of that moment of sublime dismissal. Simply put, when I handed the first draft of this piece to my wife, with its opening paragraph celebrating National Poetry Month, she gave me the Bert Cooper look. Whooooo cares? “Most people,” says she, “think of April as Tax Month.”

Stevens Unbuttoned

Granted the pomposity of a national month, but it does offer a chance to at least acknowledge the Valentine’s Day death of the former U.S. Poet Laureate Philip Levine, and the news last week of the passing of Nobel laureate Tomas Tranströmer, plus my belated discovery of Wallace Stevens’s “Adagia,” which I found by doing a search pairing poetry and austerity, the Orwellian buzz word that you will know even if all you ever read is Paul Krugman. A few clicks of the mouse and up pops “Money is a kind of poetry.” Intrigued by that message out of cyberspace from the austere author of “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” I looked further and found a proverbs-gone-wild one-man jam session he calls “Adagia.” This is Stevens as I’ve never seen him, unbuttoned, unplugged, unbowed, and unapologetic: we’re in his workshop, the rag and bone shop of his heart, his suit coat is off, his sleeves are rolled up, his tie is loose and flying in the wind though he’s sitting still, unburdening himself in the spirit of Whitman’s “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.”

This is the same Wallace Stevens who came to Princeton in the summer of 1941 to deliver a lecture titled “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words” for a collection of essays edited by Allen Tate and eventually published by Princeton University Press as The Language of Poetry. In a letter written after the event, Stevens says the lecture was “worth doing (for me), although the visit to Princeton gave me a glimpse of a life which I am profoundly glad that I don’t share. The people I met were the nicest people in the world, but how they keep alive is more than I can imagine.”

“The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words” would work as well as “Adagia” for the elemental questions Stevens is asking, such as what’s poetry? What’s a poem or a poet? A sample of the answers: “Poetry is a purging of the world’s poverty and change and evil and death,” a poem is “a meteor,” “a pheasant,” “a cafe,” “the disengaging of (a) reality,” “a health,” “the body,” “a cure of the mind,” “a renovation of experience,” “a pheasant disappearing into the brush,” “a search for the inexplicable,” “a revelation of the elements of appearance,” “the scholar’s art,” “a nature created by the poet.” My favorite at the moment is “The poet looks at the world as a man looks at a woman.” This is someone who when people would tell him they found his poetry hard to understand would say, “I understand it; that’s all that’s necessary.” Yet here he’s somewhere on the far side of austerity: “In poetry you must love the words, the ideas and the images and rhythms with all your capacity to love anything at all.”

There’s a hint of this Stevens in a letter to Allen Tate written the October following the Princeton visit. After a politeness (“I should not trouble you again”), he goes on, noting that “when a man is interested, as you are, in honesty at the center and also at the periphery (as both of us are, I should say) you might like to know of a remark that Gounod made concerning Charpentier. He said … ‘At last a true musician! He composes in C-natural and no one else but the Almighty could do that.’”

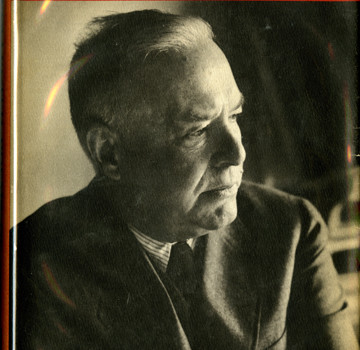

Tomas Tranströmer

Tomas Tranströmer

The reference to “a true musician” fits Tomas Tranströmer, who died March 26. Like all too many people who should know better, I had never read a word of him until I did some catching up online and found a copy of The Half-Finished Heaven (Graywolf $15), a selection made and translated by Robert Bly, which includes what may be the best poem about Schubert ever written, and by a poet pianist who loves the “stout young gentleman from Vienna known to his friends as ‘The Mushroom,’ who slept with his glasses on/and stood at his writing desk punctually of a morning./And then the wonderful centipedes of his manuscript were set in motion.”

In “Schubertiana” Tranströmer brings Schubert into Manhattan (“giant city … a long shimmering drift, a spiral galaxy”), where he knows “that right now Schubert is being played/in some room over there and that for someone the notes are/more real than anything else.” Listening to the great string quintet, the poet suddenly feels “that the plants have thoughts.” The fifth and final stanza concerns the Fantasia in f minor for two pianists: “We squeeze together at the piano and play with four hands …, two coachmen on the same coach; it looks a little ridiculous./The hands seem to be moving resonant weights to and fro, as if we were/tampering with the counterweights/in an effort to disturb the great scale arm’s terrible balance: joy and/suffering weighing exactly the same.” A reference to the “heroic” music launches a sequence that has a certain ring on April 1, 2015: “But those whose eyes enviously follow men of action, who secretly/despise themselves for not being murderers,/don’t recognize themselves here,/and the many who buy and sell people and believe that everyone can be/bought, don’t recognize themselves here.”