Digitizing Princeton Cemetery Is “A 19-Acre Jigsaw Puzzle”

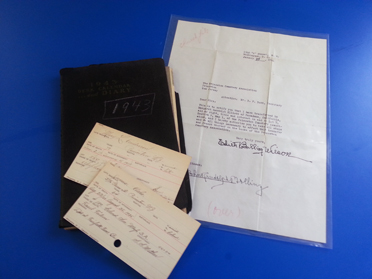

UNCOVERING THE PAST TO DIGITIZE THE FUTURE: Nassau Presbyterian Church’s project to document and digitize records from Princeton Cemetery has turned up such gems as this letter from Edith Bolling Wilson, wife of Woodrow Wilson, about the family’s cemetery plot.

From the corner of Witherspoon and Wiggins streets, Princeton Cemetery doesn’t look especially imposing. But the historic burial ground, which is owned by Nassau Presbyterian Church, stretches back to encompass nearly 19 acres. Some 25,000 interment spaces lie within its borders.

A project that will help indicate just who lies where in the 258-year-old cemetery is currently being developed by a team from the church, which is a few blocks away on Nassau Street. With the aid of old records, interment cards, military records, the daily log book, monthly financial reports, and even ground-penetrating radar, the workers are trying to clarify the history of the cemetery. At the same time, the church is being business-savvy by confirming how many graves are still available for sale.

“It’s a 19-acre jigsaw puzzle,” said Allen Olsen, who is managing the project, which will digitize cemetery maps and records. Mr. Olsen began the project two years ago and is working on it full-time with two part-time assistants. He estimates completion to be at least four years away.

Linda Gilmore, the church’s business administrator, has also been closely involved. “Obviously, from a business model, if we’ve still got space we can sell it,” she said. “But it’s much more than that. The end result of this will be a resource that has meaning for the community. It’s a historical resource we want to preserve. It’s exciting that we’re making it easier for people to find information not only about famous people buried there like Grover Cleveland or Aaron Burr, but regular people, too.”

Graves of the famous at Princeton Cemetery have long been a source of curiosity and a tourist attraction. Prominent on the list, along with Cleveland and Burr, are mathematician Kurt Godel, Paris bookshop owner Sylvia Beach, diplomat George Kennan, Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Eugene Paul Wigner, Declaration of Independence signer John Witherspoon, and the murdered parents of the Menendez brothers.

It is also the final resting place of lesser-known local residents, of all faiths. One of the common misconceptions about the cemetery is that it is only for those affiliated with the church. Another is that it’s sold out. “There are hundreds of graves still available,” Mr. Olsen said. “We’re discovering some now that we wouldn’t have known about before doing this research.”

Many believe mistakenly that the cemetery includes several signers of the Declaration of Independence (there is only one), that Albert Einstein is buried there (he isn’t, but his daughter is), and that it’s segregated. “There was segregation in the 1800s, but no longer,” Mr. Olsen said. “Anyone can buy anywhere. It’s totally open to the community.”

Records have always been kept by the cemetery workers. But when the church purchased a database and began doing the bookkeeping, staff members realized that a lot of work needed to be done. “It became clear that this wasn’t something we could do quickly,” said Ms. Gilmore. A mapping component was purchased, and Mr. Olsen began working geographically, section by section, starting with the newer sections.

He and his assistants begin by inspecting each plot and creating a paper map. They check the soil to see if there may be a burial from before 1957, when burial vaults were required. They photograph all of the headstones.

“We come back and we check the records we have,” he said. “We also check interment cards and ownership cards. Depending on the time periods, records were or were not kept well. We compare them with the cemetery log book. We also look at monthly financial reports. So we begin to compare things. And we cross-check everything to make sure we’re getting an accurate picture.”

Written records have been found in the archives of Princeton Seminary as well as in the church’s financial reports. An old file cabinet in the church basement has provided some clues, as has a cabinet full of letters. One discovery was a letter written by the wife of Woodrow Wilson about the family’s cemetery plot (see photo).

“You never know what you’ll find,” said Ms. Gilmore. “Sometimes we get information from people who come here to do research on their families. And there are so many stories. One card said ‘baby buried by the fence.’ Where by the fence? I want to know the story behind that. It’s just fascinating.”

After bringing in a company to do ground-penetrating radar, the team found 100 unmarked graves. They have also done rubbings and consulted the website Ancestry.com, and the Social Security death index, among other resources. “One of our challenges is: When is enough?,” said Mr. Olsen. “You could go on and on. We’re not doing the family geneaology for 25,000 interment spaces.”

Mr. Olsen has spoken about the project to audiences at The Nassau Club and elsewhere in town. The fact that the work won’t be finished for at least another four years is accepted and understood. “When I told one of the members of our committee on this project that after a year, we only had about 15 percent finished, he said it was okay,” Mr. Olsen said. “He said we have a moral and ethical obligation to do this, and to do it right.”