“Strange Days Indeed” — John Lennon, Kathmandu, and Loud Mouth Lime

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

The other night I found John Lennon alive and well online singing “There’s a little yellow idol to the north of Kathmandu” from “Nobody Told Me,” a song brimming over with the Lennon spirit, funny, straight-ahead, full of life, kick up your heels and let it roll. That slightly altered quote (“little” instead of “one-eyed”) from the old sidewalks-of-London busker’s delight, “The Green Eye of the Little Yellow God,” was a happy surprise.

In the aftermath of the earthquakes, I’d been searching for material for a column about Kathmandu, and the Google genies had given me one of Lennon’s most engaging post-Beatles songs, with the subtle negativity of lines like “Everyone’s a winner and nothing left to lose” harking back to the passionate positivity of “nothing you can do that can’t be done, no one you can save that can’t be saved” from “All You Need is Love,” the song he sang to the world in the summer of 1967. While the other Beatles were performing at that worldwide television event, with a host of rock luminaries joining the chorus, it was John’s song, his words, his voice sending the message. In the best and most impossible of all worlds he would be at Abbey Road right now with his three mates recording a special song to raise much-needed money for Nepal Earthquake Relief.

The Himalaya Hotel

In his account of a journey to India and Nepal, poet Gary Snyder describes coming into Kathmandu at night and stopping at the Himalaya Hotel, which was “so filthy and rat-infested” that he moved next day to a hotel “a cut better.” Some years later, on Christmas Day, delirious with fever, I found refuge in the same hotel. In the almost three weeks I was laid up there, alone, I never saw any rats, but I could hear them in the wall.

The night Gary Snyder arrived, Kathmandu “was very quiet, and most shops were closed, because everyone was inside awaiting the end of the world,” since “at 3 p.m. that afternoon … all the visible planets plus the moon and sun went into conjunction and the whole Indian nation was convinced the world would be destroyed.”

On May 20, 2015, it’s impossible to read that passage without recalling images of the devastation inflicted on Nepal on April 25 and again on May 12. Maybe the astrologers Snyder refers to were weighing cosmic conjunctions with the geophysical odds, given that the magnitude 8.0 earthquake of 1934 had caused more than 10,000 deaths and that, according to Geohazards International, the Kathmandu Valley was the most dangerous place in the world in terms of per capita earthquake casualty risk.

If you could measure events in the timeline of a life according to seismic numbers, the three weeks in Kathmandu would measure around 7.8 to 8.0 magnitude on my personal Richter scale. For a start, I was coming down with a bad cold when I landed in the center of the city, still reeling from a skidding-and-sliding-on-the-edge-of-the-abyss journey from the Indian border in the back of a truck, an experience Snyder describes as “a 12-hour ride up to 9,000 feet and back down again on the wildest, twistiest road” he’d ever been on. Having eaten nothing since the previous morning at Raxaul on the Indian border, I didn’t hesitate when a welcoming party of stoned-out fellow hitchhikers urged me to sample a concoction they called Djibouti Roo from amid an array of fat chocolate goodies displayed on an elaborately embellished silver tray. Only after I’d wolfed down one of the biggest pieces did I learn that Djibouti Roo’s street name was Mad Dog Pie, and that in addition to several melted Cadbury fruit and nut bars, it contained a super group of mind-benders, including ganja, hash, morphine, opium, cocaine, and LSD.

Falling Down

The place we were sitting in as the Mad Dog began biting me had a wildly overblown reputation in the hitchhiker interzone. Time and again on the way east we heard that the Globe Cafe was the place to head if your goal was Christmas in Kathmandu. With Shakespeare’s playhouse in mind, I fantasized a Globe-like structure surrounded by streets as narrow, winding, and funky as those of Elizabethan London. While the streets lived up to my fantasy, the Globe itself was little more than a dingy, smoky, low-ceilinged room full of westerners Getting High and Being Cool. Upstairs was a sort of flophouse dormitory where I spent the next 12 hours, “hanging on for dear life,” as the saying goes, while everything fell to pieces around me.

Getting upstairs had been an epic undertaking. As soon as I tried to stand I fell down. Stood up, took two steps, fell down again. A grim-faced Nepalese woman was showing me to the staircase, which was outside the building. Every time I toppled she glared over her shoulder, waiting for me to get back on my feet. It was beyond “if looks could kill.” Such was the depth of dismissal in her stare, this dark lady of the Globe, that hers became the face plaguing long nights and days of fever in my freezing cave of a room at the Himalaya Hotel.

Loud Mouth Lime

Among the jumble of things on the bulletin board above my desk at home is a clipping of a grinning green face with a big blue mouth and above the silly creature the words Loud Mouth Lime in purple letters. On my desk as I write is a pile of ancient Indian aerogrammes postmarked Calcutta, Benares, Allahabad and New Delhi filled to the brim with leaky ballpoint messages from me intermingling with a number of neatly written-with-fountain-pen letters on pale blue crinkly stationary with matching envelopes postmarked Berkeley, Beverly Hills, and Los Angeles from a girl I’d met three years before at a party in a Haste Street apartment house (since destroyed) in Berkeley.

Loud Mouth Lime appeared in one of the two California letters that found me in Kathmandu sweating out the nightly fevers in a U.S. Army sleeping bag laid on a charpoi in the Himalaya Hotel. My only medicine was a bottle of Aspro aspirin I bought at a nearby shop along with a packet of British arrowroot biscuits, which was all I had to eat in the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day. I had nothing to drink but the cold jars of water — “Kathmandu water is full of mica and gives everyone the runs” says Gary Snyder, though luckily for me it had just the opposite effect — and glasses of hot milky tea brought to me several times a day by a Nepalese boy no more than 10 who was only slightly less coldly indifferent to my humanity than the dark lady of the Globe had been. The way this lad scrutinized me you’d have thought that a giant green sleeping-bag caterpillar (Gregor Samsa comes to Kathmandu) had crawled into view from the rat-infested shadows. It wasn’t until around January 2 that I managed to make it half a block down New Road to the Indira Cafe to put some scrambled eggs in my stomach and to ask people who knew my friends to tell them where I was.

The low point came in the first week of January when I began to doubt that I’d ever get well. I was weak, exhausted from the strain of holding back a coughing fit I was sure would be the end of me. To this day I have no memory of picking up mail at the U.S. Embassy. All I know is that two letters from California dated December 10 and 21 showed up when my morale was in free fall. The first letter is bright, cheerful, playful, with some local color: “Buddhism is all the rage as are all mystic cults. Berkeley looks like Trafalgar Square all the time — the English beat look is in.” After apologizing for complaining about “non-thinking conformists” and “the nuts on Telegraph Avenue,” she stops writing to “go put on a Beatles record,” which makes her feel “cheery and crazy” while apparently inspiring her to clip the funny face off a packet of Kool Aid, tape it to the page, and end the letter thus, “Below is my most recent photograph which accompanied an interview which the editor of the New York Review of Books had printed last month. The interview pointed out the long winded but smiling-sardonic quality of my prose works, of which you have an example in your hand. Hoping my picture will encourage you to write, I am, as I have always been, Loud Mouth Lime.”

Strange and wonderful (“Strange days indeed,” as John sings in “Nobody Told Me”) that this grinning green face should have the power to lift me out of the endgame doldrums, even becoming a kind of comic keepsake, a joy-making version of the Green Eye of the Little Yellow God pinned on the bulletin board above my desk. Little did I know I was hooked, caught, my future foreshadowed in that silly smiling face, and in case I doubted my fate the letter from December 21 suggests that if I didn’t “freeze in the Himalayas, or get eaten by the abominable snowman, and if we get on well would I mind if we were together for most of the summer?”

Five months later in Venice we were together, and we’ve been together four decades and counting, for better or worse, ever since.

Sidewalks of London

Wondering what inspired John Lennon’s quote from “The Green Eye of the Little Yellow God,” my guess is that while watching The Late Late Show with Yoko one New York night, he had seen Charles Laughton reciting the J. Milton Hayes poem about Mad Carew and the yellow idol to the north of Kathmandu in St. Martin’s Lane (or Sidewalks of London), a film celebrating buskers and the beauty of Vivien Leigh that my wife L.M. Lime and I saw on a rented TV in Bristol in the early 1970s.

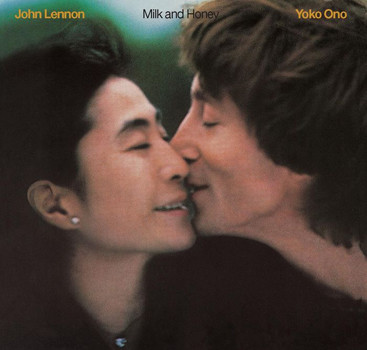

I read Gary Snyder’s “Now, India” in the October 1972 number of the journal, Caterpillar, which can be found in Snyder’s book Passage Through India (Counterpoint paperback 2009). “Nobody Told Me” is on the posthumous album, Milk and Honey (1984). As a single, it was Lennon’s last to reach the Top Ten in both the U.K. and U.S.