“Accomplishments Have No Color”: A Black History Valentine for Leontyne Price and Donald Lambert

By Stuart Mitchner

Thoughts of Valentine’s Day bring back a song I knew by heart when I was growing up. No wonder, the way my parents kept playing Nat King Cole’s recording of “Nature Boy.” They were addicted to it; so was everyone; the whole country was enthralled by the “strange enchanted boy who wandered very far, very far over land and sea.” The voice was already a pleasant part of our family’s life because of Cole’s “Christmas Song.” Now the same warm smooth deeply familiar voice that sang of chestnuts and yuletide carols and mistletoe was making me feel things I’d never felt before, exciting my imagination with dreams of distant lands and magic days, with a message about loving and being loved that was more appealing than the lessons I learned in school.

But then I heard about what happened when the singer and his family moved into a white neighborhood in Los Angeles. Their dog was poisoned; racist slurs were burned into their front lawn. I was ten. At that age it simply made no sense to me that people could hate the singer of a song with that message, a song the whole country loved.

A Diva’s Birthday

Now here we are in 2016 with the shootings in Charleston and Ferguson, the poisoned water in Flint, it’s Black History Month, and the New York Times just ran a striking series of photographs from the archives under the heading “Unpublished Black History,” including a picture from 1948, the year of “Nature Boy,” showing two second-graders at Princeton’s newly integrated Nassau Street Elementary School, one an earnest looking black girl with one arm raised, the other a white boy, chalk in hand, dutifully working out some simple addition.

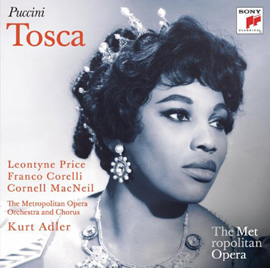

Today is also Leontyne Price’s 89th birthday. She was born in Laurel, Mississippi on February 10, 1927. Until a few days ago, I knew very little about her or her music, my only excuse being my decided lack of interest in opera when she was in her prime. In January 1961, while she was receiving a 35-minute ovation after her Met debut in Il Trovatore, I was going to jazz clubs in the Village and seeing John Coltrane play “My Favorite Things” at the Apollo in Harlem. When she was on the cover of Time, I was at a Carnegie Hall concert to benefit the African Research Foundation watching Miles Davis walk offstage after drummer Max Roach invaded the scene to protest the “colonial character” of the Foundation. As it happens, Miles Davis was a passionate admirer of Leontyne Price, writing in Miles: The Autobiography, “I love her as an artist. I love the way she sings Tosca. I wore out her recording of that, wore out two sets.”

You get an idea of what he’s talking about when you hear her sing the aria, “Vissi d’arte” from the opera Miles loved. One otherwise admiring YouTube blogger corrects the interpretation (“it’s supposed to be a prayer”), but the singer is beyond praying, she’s fighting for her spiritual life, asking why she’s been forsaken in her hour of grief: she’s not a supplicant but an artist who lived for art and lived for love and she’s singing at such a pitch, with such passion, that to hear her is like being ten years old again, feeling mindlessly happy and sad and excited by music about loving and being loved, for in the end that’s still what it’s all about.

“Old Man River”

The photos on Leontyne Price’s wikipedia page show her transition from a shy and sad-of-eye 24-year-old to Bess in Porgy and Bess to the super star of her glory years. It was while playing Bess that she fell in love with and married William Warfield, whose singing of “Old Man River” in the film Show Boat (1951) had its way with me around the time I was listening to “Nature Boy.” At 10, you cry when a cat dies, not when someone sings a song. While “Old Man River” was an epic of struggle compared to “Nature Boy,” both songs brought me to the same emotional place. Whatever love was, this music drew from it, evoked it, exalted it. You feel Jerome Kern’s music and you feel Oscar Hammerstein’s words even if you don’t understand the history. The clincher is the last verse, with the words “tired of living and feared of dying” as the camera moves in for a close-up of Warfield’s face. I was aware at the time that what I felt was what I was supposed to feel in church except that in church the lights were on, grown-ups could see you, and you had to behave yourself and try not to fall asleep or squirm too much; in the theatre it was dark and when the feeling got you no one could see it, it was all yours, whatever it was. Again, what better word for this mysterious force than love?

Witherspoon-Jackson’s Unsung Hero

You can’t talk about “Old Man River” without mentioning Paul Robeson, the most famous former resident of Princeton’s Witherspoon Jackson neighborhood. He can be seen singing the song in the earlier film of Show Boat (1936), his longer, more athletic version lifted by the presence of a chorus of workers for the last verse.

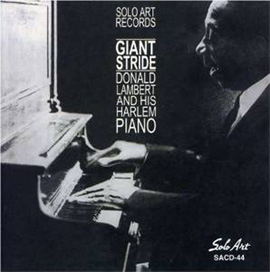

Another gifted former resident of the historic neighborhood you may not have heard of but should definitely listen to is the legendary stride pianist Donald Lambert, whose birthday is February 12. If you don’t mind the disintegrating video, you can see the man with the fastest right hand this side of Art Tatum playing breakneck renditions of Gershwin’s “Liza” and Grieg’s “Anitra’s Dance” at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival. When he was a boy of ten, Lambert played piano accompaniment to silent films on Nassau Street. His roots in the community run deep. His mother was born Elma Julia Skillman; his paternal grandmother was Annis Bayard Whycoff. When he was six his family was living with his grandfather, Israel Skillman, at 23 Jackson Street, now Paul Robeson Place. His grand-niece Leona Vernon recalled the day of his burial at Princeton Cemetery, May 8, 1962, when copies of his last album Giant Stride were handed out to family members. Leona has childhood memories of sitting with Uncle Don as he played. It must have been quite an experience. According to one listener, he could take “The Bells of St. Mary’s” and “make it sound like he was playing in St. Patrick’s Cathedral.” After listening to Lambert, jazz critic Gary Giddins heard “the emotional message of stride” as “one of liberation” or “freedom itself.” Driven by stride’s “rhythmic intoxication,” the result is “gloriously human.”

A Question of Color

Leontyne Price once said, “Accomplishments have no color.” She also said “The color of my skin or the kink of my hair or the spread of my mouth has nothing to do with what you are listening to.” I’ve just seen her sing “O patria mia” from Aida at her January 3, 1985 Met farewell. She was two years short of 60. As great as the performance, maybe greater, more “gloriously human,” is the way she receives the prolonged tumultuous ovation. With the camera on her face, close-up, she doesn’t smile. She barely blinks. It’s almost as if she were enduring a deluge of adoration. When she looks up, she’s still singing, but all the music is in her gaze. When she looks down and clasps her hands on her chest, it’s as powerful a picture of loving and being loved in return as you’ll ever see.

As far as I can tell, the only time Leontyne Price performed in Princeton was in a McCarter recital on January 17, 1955.

Donald Lambert was the subject of the first feature I wrote for Town Topics (“The Unsung Hero of Stride Piano, Princeton’s Own Donald Lambert,” Dec. 10, 2003), one of the only articles of mine that isn’t archived at www.towntopics.com.