Living In William Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury” — A Birthday Celebration

By Stuart Mitchner

Looking ahead to William Faulkner’s September 25th birthday, I reread the 1956 Paris Review interview in which he says The Sound and the Fury (1929) is the novel that caused him “the most grief and anguish,” comparing himself to the mother who “loves the child who became the thief or murderer more than the one who became the priest.”

Looking ahead to William Faulkner’s September 25th birthday, I reread the 1956 Paris Review interview in which he says The Sound and the Fury (1929) is the novel that caused him “the most grief and anguish,” comparing himself to the mother who “loves the child who became the thief or murderer more than the one who became the priest.”

For what it’s worth — a phrase to be reckoned with in this column — the novel of Faulkner’s that has afforded me the most pleasure and induced the most awe is the one that became “the thief or murderer.” In the same interview, Faulkner says that he wrote it five separate times. “It’s the book I feel tenderest towards. I couldn’t leave it alone, and I never could tell it right, though I tried hard and would like to try again.”

I read The Sound and the Fury four separate times, first when I was 19. Having found my way through it, I began reading it over again the day I finished it. Half a year later, I went back to it and finished it in two weeks. Seven years later, I reread it on the other side of the world.

Speaking of “worth,” I once owned a first edition of The Sound and the Fury that cost me $80, without the dust jacket; with a dust jacket, even in the 1980s, the price would have been way beyond my means. Although I read around in that charismatic object, I never read it through, satisfied simply to hold it, admiring the checkerboard cover design, the weight of the volume, the feel of it. In 2024 even a naked, unjacketed first like the one I once owned is spectacularly unaffordable. It seems that Faulkner’s “thief” is worth his weight in gold, and so, like a minor character in the first edition’s Dickensian rags to riches adventure, I sold Faulkner’s outlaw genius for a handsome profit, or so it seemed at the time.

This Ragged Scoundrel

Right now the novel by Faulkner that means the most to me is not only unsaleable but un-donatable; it would be a crime to leave this ragged scoundrel on any library’s doorstep, not least that of the Friends and Foundation of the Princeton Public Library, sponsors of last week’s highly successful book sale.

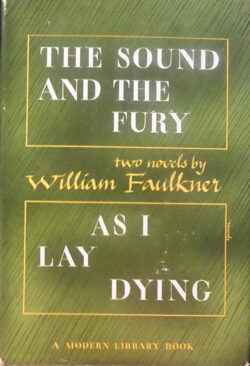

The book in question is a vandalized-looking Modern Library paperback in which the publisher paired The Sound and the Fury with As I Lay Dying (1930), a shorter book Faulkner described in terms of “simple brick by brick manual labor” next to the vagrant causer of “grief and anguish” — which has sustained the brunt of the damage, namely the rupture on page 104 that left pages 105 to 108 wholly detached, with 107 torn in four places, yet still surprisingly intact. Another much more drastic sundering occurred on page 108, where the number of blue ballpoint underlinings is evidence of my excitement as a reader, giving the impression that I not only literally “got into” the novel but actually, bodily pushed my way between the covers, totally unmooring pages 109-170, a complete unit, and still worse, doing the same to pages 173-300, leaving page 301 attached to the remainder of the volume, which survived thanks only to the fact that I was too fascinated by the villainy of The Sound and the Fury to deal with the brickwork of As I Lay Dying.

As I carefully open a book that has broken into three distinct pieces, the first thing I see is my name printed by the same ballpoint used with shameless abandon throughout. Below that are the dates of previous readings, with this later addition, in pencil: “Also finished, Katmandu, Nepal, January 1966.”

The Last Paragraph

That dated note refers not to my devastated Modern Library copy but to a cheap paperback edition bought in India, from which I saved the last page as yellowed evidence of the most satisfying reading experience of my life this side of Shakespeare. For all the previous times that I thought I “got” or was “getting” the novel, nothing close to that happened until I finished the final chapter, just me and the book curled up in an Army surplus sleeping bag. When I read the last paragraph aloud to myself in the below-freezing chill of the room, I could see my breath.

What made the Katmandu reading special was not only that the book had seen me through a mysterious, debilitating illness, but that it had slowed down and leveled out for me, the way it does in the last paragraph. Like Faulkner’s much-quoted statement, “If I had not existed, someone else would have written me,” it was as if someone else were reading with me from a book that had begun with a 33-year-old deafmute named Ben, who had passed it to his brothers Quentin and Jason, and at the end to a third-person narrative centered by the presence of a Black woman named Dilsey, one of Faulkner’s “favorite” characters “because she is brave, courageous, generous, gentle, and honest.”

In his essay in Faces in the Crowd, Gary Giddins refers to his “first readings” of The Sound and the Fury and the time spent “struggling to figure out the puzzle,” and how after “coming to it with the story in mind,” he was “moved less by its linguistic sorcery than its resonant humanity.” For me something similar happened at the very end, after Luster starts to drive the horse-drawn carriage around the wrong side of the monument, setting off the deafmute Ben: “Bellow on bellow, his voice mounted, with scarce interval for breath.” As Ben’s “hoarse agony roared around them,” Faulkner in effect gave the reins to Jason Compson, who pulled them round to the right side of the monument, making possible the last paragraph sitting all by itself at the top of page 224 of that cheap long-lost paperback:

“Ben’s voice roared and roared. Queenie moved again, her feet began to clop-clop steadily again, and at once Ben hushed. Luster looked quickly back over his shoulder, then he drove on. The broken flower drooped over Ben’s fist and his eyes were empty and blue and serene again as cornice and facade flowed smoothly once more from left to right; post and tree, window and doorway, and signboard, each in its ordered place.”

The First Page

Approaching the fiction of William Faulkner in my mid-teens, the first “never read anything like this before” moment occurred in the opening pages of Sanctuary (1931), the novel Faulkner rewrote, “trying to make out of it something which would not shame The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying too much.” Strange enough to begin with a character named Popeye, whose face “had a queer bloodless color, as though seen by electric light; against the sunny silence, in his slanted straw hat and his slightly akimbo arms, he had that vicious depthless quality of stamped tin.” Behind him a bird sang “three bars in monotonous repetition: a sound meaningless and profound out of a suspirant and peaceful following silence which seemed to isolate the spot.” Popeye “appeared to contemplate” the man on the other side of the spring “with two knobs of soft black rubber.”

When I read this passage during my sophomore year in high school, I was having a similar response to the fugue-like cool jazz of Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan, which at first I found vaguely disturbing and within a year was devoted to. With Faulkner, the devotion came later, after the fourth reading of The Sound and the Fury.

Lawrence and Faulkner

D.H. Lawrence was born on September 11, 1885. Faulkner on September 25, 1897. I’ve been wondering what Lawrence would have made of Faulkner had he lived to update Studies in Classic American Literature. While I could find nothing in Faulkner’s letters or biography about Lawrence, and since Lawrence died in 1930, a year after the publication of The Sound and the Fury, I could only imagine that after riffing on Faulkner’s excesses and extremes, Lawrence would have concluded as he does with Whitman, paying tribute to a great poet.

2024 Anniversaries

The Oxford, Miss.-based Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference celebrated its 50th anniversary this July, drawing speakers, panelists and Faulkner aficionados from as far away as France, Japan, and Kazakhstan. The theme of this year’s celebration was anniversaries since 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of Faulkner’s first printed book, The Marble Faun, the 75th of Knight’s Gambit, and the 50th of the first authorized biography, Joseph Blotner’s Faulkner. If you go to the Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference website, you’ll see a photograph of a statue of Faulkner seated on a park bench, pipe in hand, gazing out at the town square of Oxford which inspired the closing paragraph of The Sound and the Fury.