On Wallace Stevens’s Birthday: Blackbirds, Mountains, Cities, and Cathedrals

By Stuart Mitchner

I’ve just read Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” today being his 145th birthday. Why that particular poem now? Probably because it’s an infectious idea that inspires impersonation. And why 13? Why not 9 or 7? Or 10 to match the number of his birthday month?

I’ve just read Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” today being his 145th birthday. Why that particular poem now? Probably because it’s an infectious idea that inspires impersonation. And why 13? Why not 9 or 7? Or 10 to match the number of his birthday month?

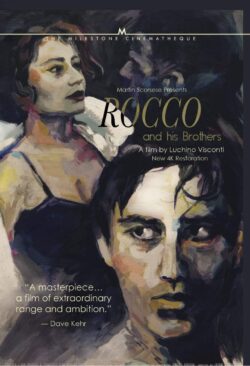

When I began writing a few days ago, I was thinking about ways of looking at Italy. What set me off was the Milan cathedral, which rises magnificently from the center of Luchino Visconti’s epic Rocco and His Brothers (1960), a film so “fearsome” (Martin Scorsese’s word) that people screamed “No!” “Stop it!” and “Basta!” when its prolonged explosions of murderous violence were first shown at the Venice Film Festival.

What happened to me? Suddenly, breathtakingly, after one of the movie’s most brutal, harrowing, hard-to-watch scenes, I found myself at the top of the cathedral surrounded by spires and pinnacles, with dizzy-making views of the city and country on all sides while straight scarily down below were tiny streetcars, busses, and human beings. I’m up there with Alain Delon’s Rocco and Annie Girardot’s Nadia, who was beaten and raped in front of Rocco by his brother Simone, mad with jealousy because Rocco and Nadia, a free-spirited prostitute, have fallen, truly, in love.

Dostoevsky and Twain

Imagine a scene out of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, as Visconti did in fact imagine it, with Delon as the Holy Fool Myshkin and Girardot as the forever fallen Nastasya Filippovna, transported from the 1860s to the 1960s, St. Petersburg to Milan and life, death, and love atop the cathedral: she’s threatened to throw herself from the roof, he’s trying to stop her, startled tourists are staring, and I’m so thrilled by the spectacular setting I feel like shouting. Along with everything else, it’s one of the greatest location shots in cinema.

“Away above, on the lofty roof, rank on rank of carved and fretted spires spring high in the air, and through their rich tracery one sees the sky beyond” — that’s how Mark Twain sees the setting in The Innocents Abroad (1869), viewing “long files of spires, looking very tall close at hand, but diminishing in the distance.” Stunned by the “wonder” of it (“So grand, so solemn, so vast! And yet so delicate, so airy, so graceful!”), Twain writes, “They say that the Cathedral of Milan is second only to St. Peter’s at Rome. I cannot understand how it can be second to anything made by human hands.”

When Annie Girardot died in March 2011, the New York Times accompanied her obituary with a still from the rooftop scene. And among the career-defining moments mentioned in the aftermath of Alain Delon’s death at 88 last month, I’ve seen none as intimate and compelling — one soulful close-up after another — as the shots of him atop the “wonder” that so moved Mark Twain.

That Singular Mountain

First published in 1917 and collected in Harmonium (1923), “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” opens “Among twenty snowy mountains,” where “the only moving thing was the eye of the blackbird.” In close proximity to Stevens’s “Blackbird” in The Collected Poems (1955) is a sonatina to Hans Christian Andersen, who looked at the cathedral of Milan in 1833 and saw “that singular mountain which was torn out of the rocks of Carrara.” Viewed “for the first time in the clear moonlight; dazzlingly white stood the upper part of it in the infinitely blue ether.” In his sonatina, the poet of twenty mountains asks, “What of the dove, / Or thrush, or any singing mysteries? / What of the trees / And intonations of the trees?” And in the last stanza: “What of the night / That lights and dims the stars? / Do you know, Hans Christian, / Now that you see the night?”

First published in 1917 and collected in Harmonium (1923), “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” opens “Among twenty snowy mountains,” where “the only moving thing was the eye of the blackbird.” In close proximity to Stevens’s “Blackbird” in The Collected Poems (1955) is a sonatina to Hans Christian Andersen, who looked at the cathedral of Milan in 1833 and saw “that singular mountain which was torn out of the rocks of Carrara.” Viewed “for the first time in the clear moonlight; dazzlingly white stood the upper part of it in the infinitely blue ether.” In his sonatina, the poet of twenty mountains asks, “What of the dove, / Or thrush, or any singing mysteries? / What of the trees / And intonations of the trees?” And in the last stanza: “What of the night / That lights and dims the stars? / Do you know, Hans Christian, / Now that you see the night?”

In a letter from 1818, Percy Shelley’s way of looking at Milan’s cathedral was to note “the effect of it, piercing the solid blue with those groups of dazzling spires, relieved by the serene depth of this Italian heaven, or by moonlight when the stars seem gathered among those clustered shapes.”

“An Awful Failure”

While stanza VIII of “Blackbird” speaks of “noble accents” and “lucid, inescapable rhythms,” Stevens knows that the blackbird “is involved / In what I know.” And when “the bards of euphony” in stanza X “cry out sharply,” I find that it helps counter the disparaging of the cathedral by Oscar Wilde in a letter from 1875 (“An awful failure … monstrous and inartistic. The over-elaborated details stuck high up where no one can see them”), as well as John Ruskin’s claim in Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) that the duomo “steals from every style in the world: and every style spoiled.” Calling it “this curious Flamboyant,” Ruskin finds “the only redeeming character about the whole” being “the crowding of the spiry pinnacles into the sky.”

Obscured by Mist

Writing in Pictures from Italy (1846), Charles Dickens brought London weather with him: “The fog was so dense here, that the spire of the far-famed Cathedral might as well have been at Bombay, for anything that could be seen of it at the time.” Flash forward to the 20th century and Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929) and the cathedral in Milan is “fine in the mist” as Frederick and Catherine pass by it, too much in love to come back for a clearer look. In stanza IV of “Thirteen Ways,” a “man and a woman are one” and “A man and a woman and a backbird are one.”

From the Center

The only reference to Milan in Stevens’s Letters (Knopf 1966) is his August 1949 response to an “unusually exciting” letter about Bergamo from a friend that prompted him to “look up the place,” whereupon he “learned for the first time what everybody else in the world has probably known for centuries; that Milan is a great center, perhaps not a great place but a great radial focus,” — which sends me to Stanza IX of “Thirteen Ways”: “When the blackbird flew out of sight / It marked the edge / Of one of many circles.” This “way of looking” works for Milan and its cathedral, which Visconti chose as the setting for the central, most significant conversation in Rocco and His Brothers, no doubt aware that its construction in 1386 coincided with the ruling power of his ancestor, Gian Galeazzo Visconti, who not only approved of the site’s centrality but hired a French engineer familiar with Rayonnant Gothic. Whether Flamboyant or Rayonnant, it’s the poet’s “radial focus” that makes “ways of looking” central to the geometry of Wallace Stevens.

Fellini, Rome, Keats

The catch is that I’ve been writing about a vicarious Milan, having never seen the fabulous cathedral in person, and yet, as should be obvious by now, I feel that I have. I could say the same about the uncut version of the three-hour-long Rocco and His Brothers that I saw for the first time last week on a Milestone DVD. Until then the only version of Visconti’s “fearsome” Rocco I’d seen was the crudely edited travesty that arrived in America only to be dwarfed by the Rome of Federico Fellini in La Dolce Vita (1960).

In a late poem, Stevens muses on “the sources of happiness in the shape of Rome, / A shape within the ancient circles of shape / And these beneath the shadow of a shape.” For all the wonders of Fellini, nothing could match what I felt standing at the age of 19 in the room where John Keats died at 26. On each of my visits to Rome in the 1960s, I visited that room adjacent to the Spanish Steps “within the ancient circles of shape” and then the Protestant cemetery near the Pyramid of Cestius, looking first at Shelley’s grave (“Nothing of him that doth fade, But doth suffer a sea-change Into something rich and strange”) before settling down in front of the grave of Keats, gazing at these words: “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.”

Inflections and Innuendoes

In August 1925, William Faulkner sent his mother a postcard of the Piazza del Duomo in Milan: “The Cathedral! Can you imagine stone lace? or frozen music? All covered with gargoyles like dogs, and mitred cardinals and mailed knights and saints pierced with arrows and beautiful naked Greek figures that have no religious significance whatever.”

In his prime Faulkner could have written the cathedral into a single soaring sentence five pages long. In Stanza V of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” Stevens doesn’t know which to prefer — “the beauty of inflections or the beauty of innuendoes / The blackbird whistling / Or just after.” Although Hemingway left the cathedral in a mist in A Farewell to Arms, his inflections and innuendoes make you see what you feel in his 1927 story “In Another Country,” which begins, “It was cold in the fall in Milan and the dark came very early. Then the electric lights came on, and it was pleasant along the streets looking in the windows. There was much game hanging outside the shops, and the snow powdered in the fur of the foxes and the wind blew their tails. The deer hung stiff and heavy and empty, and small birds blew in the wind and the wind turned their feathers. It was a cold fall and the wind came down from the mountains.”