Happening Now — Oscar Wilde, Eugene O’Neill and Ruth Wilson’s Jane Eyre

By Stuart Mitchner

There is no present or future — only the past, happening over and over again — now…

—Eugene O’Neill

The October 16, 1847 publication of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre is listed among Wikipedia’s Notable Events,1691-1900, along with the execution of Marie Antoinette (1793) and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859). As the 19th century continued “happening, over and over again,” Oscar Fingal O’Fflahertie Wills Wilde was born in Dublin on October 16, 1854 and Eugene Gladstone O’Neill surfaced in a New York City hotel on October 16, 1888.

The October 16, 1847 publication of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre is listed among Wikipedia’s Notable Events,1691-1900, along with the execution of Marie Antoinette (1793) and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859). As the 19th century continued “happening, over and over again,” Oscar Fingal O’Fflahertie Wills Wilde was born in Dublin on October 16, 1854 and Eugene Gladstone O’Neill surfaced in a New York City hotel on October 16, 1888.

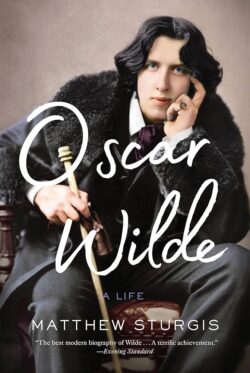

At this “now” moment, I’m doing my best to ignore the steady gaze of the colorized photograph on the cover of Oscar Wilde: A Life by Matthew Sturgis (Knopf 2021). I can imagine this supremely intense individual staring hard at the pedantic tabulator of “notable events” who failed to list the 1891 publication of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Taken in 1882 when Wilde was 28, the photograph evokes the moment in 1887 when Wilde viewed a portrait of himself and thought, “What a tragic thing it is. This portrait will never grow older and I shall. If it was only the other way.”

Since most closeup photographs of the author of Long Day’s Journey Into Night are pathologically grim, the pose on the cover of Louis Sheaffer’s O’Neill: Son and Playwright (Cooper Square Press 2002) appears perversely casual. A caption worthy of either man’s cover image would be this line from Wilde’s preface to Dorian Gray: “Those who go beneath the surface do so at their own peril.”

A Contemporary Eyre

The most compelling, intelligent, spirited Jane Eyre I ever saw was played by Ruth Wilson in the 2006 Masterpiece Theatre miniseries. The actress herself was born on January 13, 1982 in Ashford, Surrey, 100 years after the photograph of Oscar Wilde was taken. While Mike Hale’s 2014 New York Times profile mentions Wilson’s “dramatically wide lips, piercing blue-gray eyes” and “architectural eyebrows,” what makes her unforgettable as Alice Morgan, the beautiful psychopath who stalks Idris Elba’s London DCI in the BBC series Luther, is her seductively cunning mouth. It’s the combination of Jane Eyre and Alice Morgan, along with Wilson’s acclaimed dual performance as The Fool and Cordelia in the 2019 Broadway production of King Lear, that convince me she would make a fascinating 21st-century Sibyl Vane, the tragic heroine of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The most compelling, intelligent, spirited Jane Eyre I ever saw was played by Ruth Wilson in the 2006 Masterpiece Theatre miniseries. The actress herself was born on January 13, 1982 in Ashford, Surrey, 100 years after the photograph of Oscar Wilde was taken. While Mike Hale’s 2014 New York Times profile mentions Wilson’s “dramatically wide lips, piercing blue-gray eyes” and “architectural eyebrows,” what makes her unforgettable as Alice Morgan, the beautiful psychopath who stalks Idris Elba’s London DCI in the BBC series Luther, is her seductively cunning mouth. It’s the combination of Jane Eyre and Alice Morgan, along with Wilson’s acclaimed dual performance as The Fool and Cordelia in the 2019 Broadway production of King Lear, that convince me she would make a fascinating 21st-century Sibyl Vane, the tragic heroine of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

“Monstrous London”

Wilde’s gritty description of the East End is an appealing contrast to the assorted skyscrapers dominating the location shots in Luther. Equally appealing is the contrast to the fussy opening paragraph of The Picture of Dorian Gray, in a passage rich in Late Victorian atmosphere, Dorian tells Lord Henry how he discovered Sibyl Vane: “I felt that this grey, monstrous London of ours, with its myriads of people, its sordid sinners, and its splendid sins, as you once phrased it, must have something in store for me. I fancied a thousand things. The mere danger gave me a sense of delight…. I don’t know what I expected, but I went out and wandered eastward, soon losing my way in a labyrinth of grimy streets and black grassless squares. About half-past eight I passed by an absurd little theatre, with great flaring gas-jets and gaudy play-bills.”

Inside was “a tawdry affair, all Cupids and cornucopias, like a third-rate wedding-cake. The gallery and pit were fairly full, but the two rows of dingy stalls were quite empty, and there was hardly a person in what I suppose they called the dress-circle.” The play was Romeo and Juliet, and although Romeo was played by “a stout elderly gentleman” and Mercutio by “a low-comedian,” Juliet was “hardly seventeen years of age, with a little, flowerlike face, a small Greek head with plaited coils of dark-brown hair, eyes that were violet wells of passion, lips that were like the petals of a rose. She was the loveliest thing I had ever seen in my life.” Night after night Dorian went to see her: “One evening she is Rosalind, and the next evening she is Imogen. I have seen her die in the gloom of an Italian tomb, sucking the poison from her lover’s lips. I have watched her wandering through the forest of Arden, disguised as a pretty boy in hose and doublet and dainty cap. She has been mad, and has come into the presence of a guilty king, and given him rue to wear and bitter herbs to taste of. She has been innocent, and the black hands of jealousy have crushed her reedlike throat.”

As Wilde tells it, Sibyl falls in love with Dorian, loses her way as an actor, is cruelly rejected by her “Prince Charming,” and kills herself, which propels Dorian to his Faustian fate. I’d prefer a sequel in which Ruth Wilson’s Sibyl continues performing brilliantly and finds herself “happening over and over again” as a vengeful stalker pursing Dorian Gray in John Logan’s memorable series Penny Dreadful (2012-13).

Born in Times Square

From August to October 2011, Ruth Wilson played the title role of Anna Christie at the Donmar Warehouse, one of eternal London’s “little theatres.” The production won the 2012 Olivier Award for “best revival,” with Wilson receiving praise from the Guardian for “vividly” embodying Eugene O’Neill’s description of Anna as “a tall, blond, Viking-daughter” who has the haunted look of a woman traumatized by her past.

Earlier I said that O’Neill was born in a New York City hotel. In fact, the Barrett House hotel was located on the corner of Broadway and 43rd Street, in the heart of today’s Times Square. So you could say that the author of Beyond the Horizon and numerous other O’Neill plays was born around the corner from the theatres where they were first performed and six blocks south of the Eugene O’Neill Theatre on 49th Street.

My Times Square

The Times Square I haunted as a ninth-grader with a Kodak was lined with movie palaces, each with an immense billboard above the marquee, from the Paramount, the Astor and the Victoria to Loews State and the Mayfair, where the immense billboard was wrapped around the side of an otherwise mundane building. The only time I experienced a Times Square New Year’s Eve was with my parents, seeing in 1953. On November 27 of that year, O’Neill died in the Sheraton Hotel in Boston. According to his biographer Louis Sheaffer, when he was dying, he whispered, “I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room and died in a hotel room” — a quote that would surely have amused Oscar Wilde.

Jim and Josie

Apparently the Eugene O’Neill of grim closeups was no less grimly unforthcoming in interviews, since virtually all the online quotes attributed to him are taken from his plays. The line that turns up most often — “There is no present or future — only the past, happening over and over again — now” — is from his last work, A Moon for the Misbegotten, a sequel to Long Day’s Journey Into Night that I saw in 2006 at McCarter’s Berlind Theatre. The speaker is Jim Tyrone, based on O’Neill’s older brother Jamie, who was dying at the time Eugene was composing the play. Tyrone delivers the line during one of his touching, rough and tumble love scenes with Josie, who was nicely played by Kathleen McNenny the night I saw it.

Since Ruth Wilson won an Olivier for her performance as the “tall, blond” Anna Christie, she’d be my choice to play Josie, who is sketched by O’Neill as “so oversize for a woman that she is almost a freak…. Her sloping shoulders are broad, her chest deep with large, firm breasts, her waist wide but slender by contrast with her hips and thighs. She has long smooth arms, immensely strong, although no muscles show. … But there is no mannish quality about her. She is all woman. The map of Ireland is stamped on her face, with its long upper lip and small nose, thick black eyebrows, black hair as coarse as a horse’s mane, freckled, sunburned fair skin, high cheekbones and heavy jaw.”

O’Neill’s sketch of Jim Tyrone refers to his “naturally fine physique” that has become “soft and soggy from dissipation…. His eyes are brown, the whites congested and yellowish. His nose, big and aquiline, gives his face a certain Mephistophelian quality which is accentuated by his habitually cynical expression. But when he smiles without sneering, he still has the ghost of a former youthful, irresponsible Irish charm -— that of the beguiling ne’er-do-well, sentimental and romantic. It is his humor and charm which have kept him attractive to women, and popular with men as a drinking companion.”

The Last Word

The other day my son and I were on the trolley walk between the Great Road and Johnson Park School, so called because it follows the route of the streetcar that took O’Neill from Princeton to the flesh pots of Trenton in his short-lived student years at Old Nassau. I always think of O’Neill on that walk, regardless of what’s going on in the world, including presidential elections and the World Series.

Right now, in O’Neill’s no-present, no-future, forever happening past, I’m giving Oscar Wilde the last word, from the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, which my son says has inspired songs by U.K. rock groups Sweet and Nirvana: “From the point of view of form, the type of all arts is the art of the musician. From the point of view of feeling, the actor’s craft is the type.”