On Ezra Pound’s Birthday: Life and Contacts

By Stuart Mitchner

Denizens of YouTube’s cosmic jukebox can celebrate Ezra Pound’s birthday by listening to him deliver Part I of his landmark poem Hugh Selwyn Mauberly (Life and Contacts). The reading was reportedly recorded in 1959 when he lived in Castle Brunnenburg in the Italian Tyrol, some 39 years after the poem was first published and 65 years before the 2024 election. With a few taps on the keyboard, you can go eye to eye with the old poet, who describes himself as E.P. “born in a half-savage country, out of date” — actually Hailey, Idaho Territory, U.S.A., October 30, 1885.

Denizens of YouTube’s cosmic jukebox can celebrate Ezra Pound’s birthday by listening to him deliver Part I of his landmark poem Hugh Selwyn Mauberly (Life and Contacts). The reading was reportedly recorded in 1959 when he lived in Castle Brunnenburg in the Italian Tyrol, some 39 years after the poem was first published and 65 years before the 2024 election. With a few taps on the keyboard, you can go eye to eye with the old poet, who describes himself as E.P. “born in a half-savage country, out of date” — actually Hailey, Idaho Territory, U.S.A., October 30, 1885.

The Voice

Pound’s voice stays with you. At 74, he comes through alive and slashing, with phrases that resonate a week before the Fifth of November:

“a tawdry cheapness / Shall outlast our days…”

“All men, in law, are equals…We choose a knave or an eunuch / To rule over us.”

“What god, man, or hero / Shall I place a tin wreath upon?”

As Pound gathers steam, he could be referring to any war anywhere, any political situation —

“These fought …. Some quick to arm, / some for adventure, / some from fear of weakness, / some from fear of censure, / some for love of slaughter, in imagination, learning later …” They “walked eye-deep in hell / believing in old men’s lies, then unbelieving / came home, home to a lie, / home to many deceits, / home to old lies and new infamy; / usury age-old and age-thick / and liars in public places.”

Pound and Politics

Today the lies, infamy, and deceit are spread through eruptions of misinformation on a scale inconceivable in 1920 or 1959. The term “usury” is also a key to Pound’s personal prejudice, in this instance the stereotypical Jewish money-lender embodied by the war profiteers that Pound blamed for the First World War, as well as for creating and exploiting the Second.

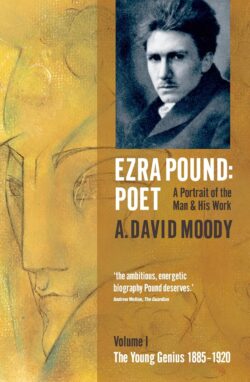

In his preface to Volume I of Ezra Pound: Poet (Oxford 2007), A. David Murray describes Pound leaving London in 1920 knowing “that in his time and culture any earthly paradise would have to be forged in the inferno of imperial capitalism.” His poetry is “prophetic, at once revealing something of the mystery of the contemporary money-dominated and market-oriented Western world, and envisioning a wiser way of living.”

During Pound’s 1960 Paris Review conversation with poet Donald Hall, he recalls visiting his father, an assistant assayer at the U.S. mint in Philadelphia. After “the Democrats finally came back in [in 1893],” the silver dollars were “recounted, … four million dollars in silver. All the bags had rotted in these enormous vaults, and they were heaving it into the counting machines with shovels bigger than coal shovels.” For Pound, this image out of the “capitalist inferno,” the “spectacle of coin being shoveled around like it was litter — these fellows naked to the waist shoveling it around in the gas flares — things like that strike your imagination.”

By 1940 Pound was calling the Democratic president “that brute Rosefield,” FDR being one of the prime targets of his pro-Fascist wartime broadcasts from Mussolini’s Italy — for which he was arrested in May 1945 by U.S. forces and held in an American military detention center near Pisa. Imprisoned for weeks in a wire cage open to wind and rain, Pound suffered “a nervous collapse from the physical and emotional strain,” according to the introduction to the 2003 paperback edition of The Pisan Cantos: “Out of the agony of his own inferno came the eleven cantos that became the sixth book of his modernist epic, The Cantos, itself conceived as a Divine Comedy for our time.”

Published by New Directions, The Pisan Cantos won the 1948 Bollingen Prize for poetry, awarded by the Library of Congress. “The honor came amid violent controversy, for the dark cloud of treason still hung over Pound,” who was incarcerated in a Washington, D.C., hospital for the insane until poets and authors rallied around him and gained his release in 1958. According to Ernest Hemingway, who later expressed his debt to Pound in A Moveable Feast, “Whatever he did has been punished greatly and I believe he should be freed to go and write poems in Italy where he is loved and understood.”

“Mr. Nixon”

Pound lived in Italy through the 1960s, giving annual readings at Spoleto’s Festival of Two Worlds from July 1966 up until the year preceding his death at 87 (November 1, 1972), six days before Richard Nixon’s landslide victory over George McGovern. The fact that a “Mr. Nixon” turns up in Part II of Mauberly is among the coincidences inherent in the fact that Pound’s birth and death dates precede American elections. In Murray’s biography, which is subtitled The Young Genius: 1885-1920, “Mr. Nixon” is numbered among Mauberley’s “contacts,” none of whom, Pound claimed “were to be identified with particular people known to him.”

Murray goes on to name some possibilities in the London group Pound was associated with, most prominently his “stylist” friend Ford Madox Ford. Among “Mr.Nixon’s” literary tips, the final piece of advice was: “And give up verse, my boy, / There’s nothing in it.”

Whether or not Ford actually inspired “Mr. Nixon,” he has given the world an image of Pound arriving in London at 22 “with the step of a dancer, making passes with a cane at an imaginary opponent” while wearing “trousers made of green billiard cloth, a pink coat, a blue shirt, a tie hand-painted by a Japanese friend, an immense sombrero, a flaming beard cut to a point, and a single, large blue earring.”

Character and Poem

Speaking of Mauberley as a character, Murray suggests that he has “all Pound’s mastery of the art of composing words and images into music, but he is his opposite when it comes to the relations of life and art. Not life for art’s sake, but art for life’s sake has always been Pound’s cry.” Discussing Mauberly as a poem, T.S. Eliot (whose 1922 masterpiece The Wasteland lives and breathes in great part thanks to Pound’s vision of art for life’s sake) declares it “a great poem” and “a positive document of sensibility. It is compact of the experience of a certain man in a certain place at a certain time; and it is also the document of an epoch; it is genuine tragedy and comedy; and it is, in the best sense of [Matthew] Arnold’s worn phrase, a ‘criticism of life.’”

A Certain Place

A couple in their twenties traveling through Italy in the summer of 1966 found themselves in Spoleto on the day Ezra Pound was reading at the Festival of Two Worlds. The legendary poet had not been on their schedule; they didn’t even know that he was still alive; it was as if the Lost Generation had been found on a rainy/sunshiny day in early July. There he was, the last survivor of 1920s Paris, as alive as we were, breathing the same air, with his white forked beard, his hair a white cloud, eyes in a blue mist, his voice a whisper compared to the voice on the record made seven years before. And when he said he was reading from something he called “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley,” we had no idea what to expect from such a dull, unpromising title, although the first lines sounded familiar, worthy of the legend standing behind the lectern: “For three years, out of key with his time, he strove to resuscitate the dead art of poetry.”

And how did it feel when we came out of the building in a mist of sun and rain and saw him in the street, braced on his cane? I’ll quote from Mauberley, the last three lines from “Envoi,” which he’d delivered toward the end of the reading and which are printed in italics in T.S. Eliot’s edition of Pound’s Selected Verse: (Faber & Gwyer 1928):

Siftings on siftings in oblivion,

Till change hath broken down

All things save Beauty alone.

Ginsberg Blesses Pound

A year later, in the last week of October, Allen Ginsberg visited Pound in Venice, playing him a tape of contemporary rock: The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” and “Yellow Submarine,” Bob Dylan’s “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” “Gates of Eden,” and “Absolutely Sweet Marie,” and Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman.” Pound sat silent throughout the concert, responding with “a slight smile” to the line “No one was saved” from “Eleanor Rigby” and to “six white horses that you promised me were finally delivered down to the Penitentiary” from “Sweet Marie.”

A week later, in an apparent reference to Pound’s antisemitic wartime broadcasts. Ginsberg announced, “I’m a Buddhist Jew,” going on to mention “the series of practical exact language models which are scattered throughout the Cantos like stepping stones – ground for me to occupy, walk on – so that despite your intentions the practical effect has been to clarify my perceptions – and anyway, now, do you accept my blessing?” To which Pound said, “I do,” admitting “my worst mistake was the stupid suburban prejudice of anti-Semitism, all along, that spoiled everything.” Said Ginsberg, “Ah, that’s lovely to hear you say that…”

Note: Thanks are due to the Princeton Public Library, where I found Volume I of A. David Murray’s Ezra Pound: Poet (Oxford 2007), along with Volume II, The Epic Years 1921-1939, and Volume III, The Tragic Years 1939-1972.