Mixing It Up with Phil Lesh and Ezra Pound on The Day After

By Stuart Mitchner

Writing on Sunday, November 3, I’m trying not to worry about the state of the nation on Wednesday, November 6. The backyard is painted yellow gold with leaves; the bird baths, front and back, are thriving; the new birdfeeders are wildly popular, and we’ve had a month of classic autumn weather — if you don’t count the drought. But I might as well be on “Dover Beach” with Matthew Arnold, the night-wind on my face on a sunny afternoon, the closing lines like one long sentence — “the world which seems to lie before us like a land of dreams, so various, so beautiful, so new, hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, not certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; and we are here as on a darkling plain swept with confused alarms of struggle and light, where ignorant armies clash by night.”

Writing on Sunday, November 3, I’m trying not to worry about the state of the nation on Wednesday, November 6. The backyard is painted yellow gold with leaves; the bird baths, front and back, are thriving; the new birdfeeders are wildly popular, and we’ve had a month of classic autumn weather — if you don’t count the drought. But I might as well be on “Dover Beach” with Matthew Arnold, the night-wind on my face on a sunny afternoon, the closing lines like one long sentence — “the world which seems to lie before us like a land of dreams, so various, so beautiful, so new, hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, not certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; and we are here as on a darkling plain swept with confused alarms of struggle and light, where ignorant armies clash by night.”

How about going with something a little lighter but dark around the edges, like Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” (“let us stop talking falsely now, the hour’s getting late”) — or else “Desolation Row,” even if Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot are “fighting in the captain’s tower.” Funny, as much as Allen Ginsberg admires Dylan, he complains about that line on allenginsberg.org because “Eliot and Pound were friends.” Hey, this is Bob Dylan, this is what he does, he mixes things up, so does Pound, who didn’t ride to the rescue of The Waste Land with gentle suggestions: he struck the lance of his pen deep into the heart of the first page. Otherwise we’d have something called He Do The Police In Different Voices.

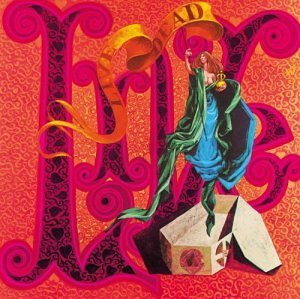

OK, we’ll mix vintage Ezra with some buoyant electric bass from the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh, who died late last month. Lesh’s playing on “Dark Star” and “Alligator” kept me going as I tried to read The Cantos and early troubadour poems like “Na Audiart,” which reads like a verse translation of Lesh’s bassline, with the Dead putting the pulse of life into Pound’s refrain “Audiart, Audiart.”

Jiu Jitsu

In the unlikely event of an actual physical confrontation, the dashing young Pound — the ex-Wabash College faculty member who stormed London’s Bohemia in 1908 — would be a fearsome opponent. In the second volume of Writers at Work (Viking Compass 1965), Robert Frost recalls the time Ezra demonstrated his jiu jitsu skills in a London restaurant: “Wasn’t ready for him at all. I was just as strong as he was. He said, ‘I’ll show you, I’ll show you. Stand up.’ So I stood up, gave him my hand. He grabbed my wrist, tipped over backwards and threw me over his head. Everybody in the restaurant stood up.’’ Frost adds that Pound also “cultivated the French style of boxing. They kick you in the teeth.” Frost is a good sport about it, even if he can’t help quoting a teacher of Pound’s at Penn who “had him in Latin” and claimed that “Pound never knew the difference between a declension and a conjugation.”

Learning from Poirier

The jiu jitsu story is from a 1960 Paris Review interview conducted by Richard Poirier, whose Introduction to Graduate Study class at Rutgers in the late 1960s starred Eliot and Joyce. Thanks to his Partisan Review essay “Learning from the Beatles,” the students who entered the program way back then were more conversant with the Doors and the Grateful Dead and the Beatles’ White Album than they were with Shakespeare and Milton. Poirier also had his own cunning way of “mixing things up,” both in his teaching and writing (The Performing Self, Oxford 1971), which may be one reason I’m bringing together “strange bedfellows” like Lesh and Pound. “Think of putting together a mobile,” Poirier once told me. “A piece here, a piece there, no special order at first, just assemble it and make sure it’s balanced.”

“Dark Star”

I once spent the night in the New York apartment of a fellow grad student with a fondness for the Dead. He’d just bought the Live/Dead double album, which had been recorded in early 1969 at Fillmore West and the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco. Scrunched on a sofa in the disorder of his living room, I found sleep hard to come by, no wonder, since he played Live Dead over and over deep into the night as I drowsed in and out of a “Dark Star” dream world haunted by the subtle poetry of Phil Lesh’s bass.

I once spent the night in the New York apartment of a fellow grad student with a fondness for the Dead. He’d just bought the Live/Dead double album, which had been recorded in early 1969 at Fillmore West and the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco. Scrunched on a sofa in the disorder of his living room, I found sleep hard to come by, no wonder, since he played Live Dead over and over deep into the night as I drowsed in and out of a “Dark Star” dream world haunted by the subtle poetry of Phil Lesh’s bass.

Though the lyrics of “Dark Star” were a lesser feature of the experience, “Shall we go, you and I” is a direct echo of T.S. Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” in which Eliot does everything but hold out his hand and pull you aboard. “Let us go then, you and I” opens one of the most inviting poems in English, in marked contrast to Pound’s The Cantos (New Directions 1989), which I found massively uninviting until last week, when the 818-page life’s work Pound liked to call his Divine Comedy began making sense, its vastness and allusiveness reflecting the soundscape of the Net where anything might turn up, including an allusion to the cycle of folk tales sometimes known as “the grateful dead.”

A Talk With Lesh

A year after my wife and I saw Pound at the Spoleto festival in July 1966, we saw the Grateful Dead in Ann Arbor. When the show was over, we talked with Lesh about “the long strange trip” in music he’d taken since his time in Berkeley, where he and my wife had had mutual friends. Lesh told us that Jerry Garcia happened on the name “grateful dead” in an old dictionary (a page from the volume in question can be seen on ultimate-guitar.com). “The door opened and I walked in,” Lesh said after we asked how he and the Dead happened. “It was that simple.” Not so simple has been the recorded evolution of the Grateful Dead as a lifework like the Cantos, extended beyond the studio into a world in itself by devoted generations of so-called Deadheads.

An “Unreasonable Project”

Several months after our August 1967 conversation, Lesh and the Dead were in L.A. recording their second album Anthem of the Sun, which took six months compared to the three days needed to complete their self-titled Warner Bros debut. Company president Joe Smith called Anthem “the most unreasonable project with which we have ever involved ourselves.” Lesh apparently bore the brunt of the blame since what happened in the studio had been inspired by his fascination with the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage, and John Coltrane.

Mixing “Anthem”

Although I knew nothing about the studio back story, Anthem was the Dead record I kept coming back to, drawn by the feeling that I was in touch with something comparable to the bassline visitation that dreamed me through my night with the Live Dead. Blair Jackson’s liner notes describing the recording sessions suggest a wild variation on the idea of “mixing things up.” After the producer walked out, the band took full advantage of the situation, creating layered versions of the album’s five main compositions “by combining studio tracks with a number of live performances of the tunes recorded on the road during the fall of ‘67 and the winter of ‘68.” Says Jerry Garcia: “We were making a collage … where you are actually assembling bits and pieces toward an enhanced non-realistic representation. In other words, we mixed it for the hallucinations.”

Pound Post-Election

On my way into The Cantos, it helped to follow Allen Ginsberg’s example, taking advantage of “the series of practical exact language models which are scattered throughout like stepping stones” for readers to “occupy, walk on” in order to clarify their perceptions.” Reading the coded cantos Pound wrote while he was in a post-war detention camp in Pisa, I can imagine a writer in today’s divided nation doing something similar, mixing obscure under-the-radar allusions crafted to escape the meddling of malign authorities.

Let It Shine

I figure there must be some Deadheads at Trump’s rallies. Sometimes I imagine someone behind the scenes blasting out “Turn on Your Lovelight” from Live/Dead, really loud, and suddenly all the haters are dancing and singing along, “Let it shine on me, let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.”