On the Brilliance of “My Brilliant Friend”

By Stuart Mitchner

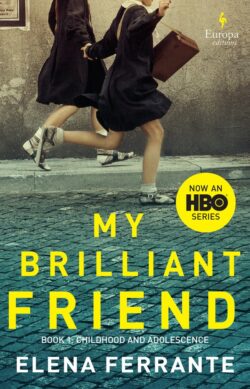

The television adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (Europa 2012) made its HBO debut on November 18, 2018. After watching the concluding episode of the fourth and final season on November 11, 2024, my wife and I sat in stunned silence, feeling as if we’d just seen an unquestionably great film in spite of a pandemic-mandated two-year “intermission.” It didn’t matter that we’d had to rewatch some of the third season to catch up with the tangential characters, events, and relationships. What made it possible to appreciate the film as a single unified work of cinematic art was the evolution of the extraordinary friendship suggested by the title. All the other characters and plotlines and subplots were ultimately and necessarily secondary, “supporting” in every sense of the word. Postwar Italian history, politics, communism, fascism, drugs, family life, black marketeers, local color — nothing compared in significance to the relationship between Rafaella “Lila” Cerullo and Elena “Lenù” Greco.

The television adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (Europa 2012) made its HBO debut on November 18, 2018. After watching the concluding episode of the fourth and final season on November 11, 2024, my wife and I sat in stunned silence, feeling as if we’d just seen an unquestionably great film in spite of a pandemic-mandated two-year “intermission.” It didn’t matter that we’d had to rewatch some of the third season to catch up with the tangential characters, events, and relationships. What made it possible to appreciate the film as a single unified work of cinematic art was the evolution of the extraordinary friendship suggested by the title. All the other characters and plotlines and subplots were ultimately and necessarily secondary, “supporting” in every sense of the word. Postwar Italian history, politics, communism, fascism, drugs, family life, black marketeers, local color — nothing compared in significance to the relationship between Rafaella “Lila” Cerullo and Elena “Lenù” Greco.

Hand in Hand

Picked by series creator Saverio Costanzo (Hungry Hearts) to direct the final season, Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin, Daughter of Mine) was particularly engaged by the sequences where Lila and Elena “parent together”: “It was so emotional when we were shooting because we built a family in this building with two mothers and two daughters — it was incredible.” After referring to the complex challenge of directing Irene Maiorino as Lila and Alba Rohrwacher as Elena, Bispuri said, “When I work with them, I use this expression: I like to take their hand in my hand.”

Bispuri’s phrasing echoes definitive moments in the early chapters of My Brilliant Friend, which like the other three books in the Neapolitan Quartet, is narrated by the grown-up Elena Greco (the film’s voiceover is done throughout by Alba Rohrwacher). When Lila gives Elena her hand on their first shared adventure, to confront Don Achille, the neighborhood “ogre of fairy tales,” this gesture “changed everything between us forever.” Convinced that the “ogre” had stolen their dolls, the girls have climbed four flights of stairs “toward the greatest of our terrors at the time.”

On the next adventure, Lila leads them into the unknown world beyond the neighborhood. As they approach the dark tunnel marking the boundary, “we held each other by the hand and entered.” But once the tunnel is out of sight behind them, Lila’s mood darkens, she becomes uneasy, and keeps looking back. Behind them “everything was becoming black, large heavy clouds lay over the trees.” Suddenly Lila decides to turn around, dragging them homeward. “A violent light cracked the black sky, the thunder was louder, Lila gave me a tug, and I found myself running.” Heavy rain descends on them: “We were soaked, our hair pasted to our heads, our lips livid, eyes frightened.” As they go back through the tunnel, Lila “let go of my hand.”

“For two years it was like I went into a tunnel” is the way Bispuri describes her direction of the final season: “That was the only way to go so in depth.” In James Poniewozik’s November 14 New York Times review, he praises the way Bispuri “conveys a brutal intimacy by holding on tight head shots of the actors. In this story of people who cannot escape their closeness, the viewer cannot either; the camera pushes you into the hot faces of anger, lust, grief.” Commenting on the earthquake episode in which Lila seems to be reliving the childhood trauma of the storm and the tunnel: “You can build as stable a life for yourself as you can. But you can never shake the fear, or the possibility, that the ground might split open and horrors escape from hell.”

Reading Together

In the first book of My Brilliant Friend, Elena Ferrante creates one of the most compelling, moving, and true depictions of childhood I’ve ever read. Even so, the series surpasses the novel in the scene where the girls, Elena (Elisa Del Genio) and Lila (Ludovica Nasti), read Little Women together, cradled in one another’s arms, a shared embrace with the book at the center, as if the two girls were one.

In the first book of My Brilliant Friend, Elena Ferrante creates one of the most compelling, moving, and true depictions of childhood I’ve ever read. Even so, the series surpasses the novel in the scene where the girls, Elena (Elisa Del Genio) and Lila (Ludovica Nasti), read Little Women together, cradled in one another’s arms, a shared embrace with the book at the center, as if the two girls were one.

The copy of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women the girls share was bought with the money that Lila shamed out of Don Achille when they confronted him about the stolen dolls. “We clutched each other’s hand tightly, waiting for him to bring out a knife. Instead he took out his wallet, opened it, looked inside, and handed Lila some money. ‘Go buy yourself dolls,’ he said.” Their shared copy of Little Women was “yellowed by the sun,” having been displayed in the stationer’s window “forever.” Meeting in the courtyard to read it, “either silently, one next to the other, or aloud,” they “read it for months, so many times that the book became tattered and sweat-stained, it lost its spine, came unthreaded, sections fell apart. But it was our book, we loved it dearly.”

Lila’s Genius

If you fall in love with the series during the reading scene, as I did, it’s hard not to think that the story is primarily about, as I suggested, the evolution of an extraordinary friendship. In fact, My Brilliant Friend is ultimately driven by the disturbed genius inhabiting a Neapolitan shoemaker’s daughter. In a sequence toward the end of the novel, when the girls are in their mid-teens, Elena is telling Lila about the theology course she’s taking. She doesn’t know what to think about the Holy Spirit. How can it make sense to consider it separate from God and Jesus? Lila’s response not only stuns her to the core, but inspires the eventual writing of the book: “We are flying over a ball of fire. The part that has cooled floats on the lava. On that part we construct the buildings, the bridges, and the streets and every so often the lava comes out of Vesuvius or causes an earthquake that destroys everything. There are microbes everywhere that make us sick and die. There are wars. There is a poverty that makes us all cruel. Every second something might happen that will cause you such suffering that you’ll never have enough tears. And what are you doing? A theology course in which you struggle to understand what the Holy Spirit is? Forget it, it was the Devil who invented the world, not the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.”

Working with a Ghost

Interviewed by the Guardian’s Kathryn Bromwich (Nov 11, 2018), series creator Saverio Costanzo, who directed the first season, talks about his strange collaboration with Ferrante, who writes under a pseudonym and communicates by email to protect her privacy. Says Costanza, “She gave us very good advice, she was not defensive at all — just guarded.” At the same time, “It’s like working with a ghost. It’s kind of a nightmare…. She goes for truth even when she writes to you. So she can be not at all delicate,” and yet “the fact that the communication was solely through writing kept the relationship healthy, work-related, focused on generating clear ideas.”

The Other Naples

Ferrante’s obsession with privacy reminds me of Roberto Saviano, the author of the non-fiction “personal journey” that inspired the other Neapolitan series presented on HBO. At the time I reviewed Gomorrah, on January 12, 2022, Saviano had been in hiding since 2006 (according to his Wikipedia, he still is), living his life in fear, his every move outside each so-called “safe house” organized around police escorts and armored vehicles.

Writing on the first anniversary of the January 6 attack on the Capitol, I began by quoting some words that accorded with my general impression of Gomorrah — “I dream of a darkness darker than black.” The quote comes from the journal of an officer who “felt himself spiraling downward in the days following the attack.”

The television images replayed to mark the anniversary of the insurrection made it clear that no amount of simulated murder and mayhem, however brilliantly shot and graphically executed, could compare with the violence of that real-life event, and for all the staged shootings, beatings, throat-slashings, and other innumerable acts of violence in Gomorrah, nothing could match the glaring intensity of the moment a young cop is crushed by the roaring, pounding mob, pinned against a door frame, screaming in pain, crying out in agony. The real thing is very hard to watch.

Saviano’s Gomorrah begins with quotes from Hannah Arendt (“Comprehension … means the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality — whatever it may be”) and Machiavelli (“Winners have no shame, no matter how they win”).