A Game of “Authors” with Jane Austen and Mark Twain

By Stuart Mitchner

One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.

—Jane Austen (1775-1817), from Emma

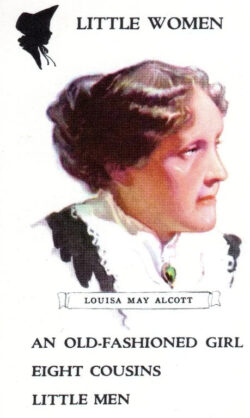

According to A Book of Days for the Literary Year, the week of December 15 begins with the publication of Emma, a day before Jane Austen’s 40th birthday in 1815. Emma Woodhouse’s comment about a divided understanding of the world’s pleasures, spoken soon after she herself disastrously misunderstands a courtship charade, has me thinking about Authors, the card game that my parents and I played when I was a boy. The fact that Jane Austen had been overlooked by the creators of the game (the only female being Louisa May Alcott) naturally didn’t occur to me, although when my wife and I played Authors with our son decades later, her absence was front and center. How could they leave her out, a question that had serious resonance on the Christmas morning I gave my wife illustrated editions of Persuasion and Mansfield Park.

According to A Book of Days for the Literary Year, the week of December 15 begins with the publication of Emma, a day before Jane Austen’s 40th birthday in 1815. Emma Woodhouse’s comment about a divided understanding of the world’s pleasures, spoken soon after she herself disastrously misunderstands a courtship charade, has me thinking about Authors, the card game that my parents and I played when I was a boy. The fact that Jane Austen had been overlooked by the creators of the game (the only female being Louisa May Alcott) naturally didn’t occur to me, although when my wife and I played Authors with our son decades later, her absence was front and center. How could they leave her out, a question that had serious resonance on the Christmas morning I gave my wife illustrated editions of Persuasion and Mansfield Park.

John Greenleaf Who?

The next stop in the Literary Year’s “week that was” is December 17, 1807, which marks the birth of John Greenleaf Whittier, the only author in the game whose presence there I didn’t understand. I’d heard of all the others thanks to my obsessive reading of Classic Comics, but my parents were never able to answer my question about Whittier, as in what’s he doing here? And even though he merits a place in the Literary Year, the editors utterly ignore him after noting Atlantic Monthly’s party to celebrate his 70th birthday in 1877, where that rogue Mark Twain stole the show, “shocking the diners” by comparing his fellow dinner guests Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes “to three drunken tramps in the Sierras.”

Reading Twain

What can you say? As you can see from the face on the Authors card, Twain’s a man to reckon with. Still, thanks mostly to my mother, who read all of Tom Sawyer aloud to me one summer, he was the author I knew best. As stern as he looks under those beetling white brows, he could always make me laugh, a tribute to my Missouri-born mother’s ability to take on different voices, although the passages she did most memorably were the love scenes between Tom and Becky, especially when they were lost in the cave.

Dickens Owns the Date

With Christmas only a week away, December 17 obviously belongs to Charles Dickens, that being the day in 1843 when A Christmas Carol was published. It’s also one of the four titles on the Dickens card, along with The Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, and Oliver Twist. One of the pleasures surely more than half the world can understand is when Scrooge follows Marley’s ghost to the window and looks out at the night “filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste.” And then when he looks out on the brightness of Christmas morning in an ecstasy of light and warmth and hope and good cheer after the spirits of Christmas past, present, and future have transported and transformed him.

The card portrait of Dickens in profile always struck me as impressively lifelike, perhaps because of the touch of color in his cheeks and his steady gaze. In the words of the American Antiquarian Society’s entry on the origins of the game, “Before the world ogled over athletes and movie stars, the greatest celebrities were authors. People traveled far and wide to see the performances of Charles Dickens and Mark Twain as they read their stories aloud, complete with character voices and, in Dickens’s case, such taxing physicality that some believe it may have hastened his death.”

Things Get Grim

December 18 is a dark date in the Literary Year. John Dryden is attacked by minions of the Earl of Rochester in 1679; the poet Samuel Rogers (The Pleasures of Memory) dies in 1855; born that day in 1870, storywriter Saki (H.H. Munro) is killed in battle in France in 1916. December 19 isn’t much better. In 1832, New Jersey poet Philip Freneau gets lost in a snowstorm while returning from a tavern and dies near his home in Middletown Point; in 1848 Emily Brontë dies of consumption at 30, after catching cold at her brother Branwell’s funeral. For December 20, the editors resort to Mark Twain again to lighten things up, as he did in 1871, comparing himself to George Washington (“I have a higher and greater standard of principle. Washington could not lie. I can lie, but I won’t”). In 1968, however, John Steinbeck (The Grapes of Wrath) dies of a heart ailment in New York City, and on December 21, 1940, in Los Angeles, Princeton’s prodigal son F. Scott Fitzgerald dies at 44 of a heart attack, leaving his Hollywood novel The Last Tycoon unfinished.

A Special December 18

I’ve been pacing around this particular date for over a week. Needless to say, my mother isn’t in the Book of Days for the Literary Year. She did desperately want to be a writer and kept at it from her late teens to her early forties. The closest she came to success was in 1950 when the Kenyon Review published her story about a paranoid judge, which led to a mention in Best American Short Stories of 1951 and an agent and several years of top publishers reminding her of the bestselling novel they were sure she “had in her.” She tried, leaving dozens of aborted opening chapters, with whole typewritten paragraphs x-ed out. Instead, she produced some stories her agent sent around, but most of the time she sat at the Royal portable typing hundreds of pages of an extremely personal journal that answered many of the questions I had about her life but never had the nerve to ask.

I found her papers in a blue vinyl suitcase the day she died on December 18, 1978. I sat up all night reading her, getting to know the woman she was in her prime, a ritual I have followed every December 18 for decades.

“I Wrote a Story!”

Of all the glimpses of my mother I found in the journals, the one that spoke to me, writer to writer, begins, “But now look what’s happened! I’ve written a story clear through! It’s a spring night with the wind demanding to be heard and rain falling every now and then, gently. When I come out, I find a misty world dripping like a freshly sprayed vegetable, the full moon like a huge street lamp seen through the rain. And how funny it is what the touch of the wind on my face does to me, this soft, restless wind, reaching right inside me and touching every sense I possess. I could do desperate and violent things when the wind is this way. I started writing at 1:30 A.M. and finished the story by about 5:00. It runs to 5000 words. Delirious with happiness I celebrate by going for a long drive just as the sun’s rising.”

Sharing a Book

That summer of sharing Tom Sawyer, cuddled up on the big bed, my mother reading, me listening with eyes closed, imagining Tom and Becky in the cave, came back full force when I saw the two Neapolitan schoolgirls cuddled together sharing their copy of Little Women in My Brilliant Friend. That’s when I bonded with the series. Just now I looked at Louisa May Alcott’s portrait card in the Authors deck. She’s shown in profile, a handsome woman in middle age, her gaze fixed as if on some distant prospect. Her expression is mild, as if she were picturing future readers like the girls in My Brilliant Friend.

That summer of sharing Tom Sawyer, cuddled up on the big bed, my mother reading, me listening with eyes closed, imagining Tom and Becky in the cave, came back full force when I saw the two Neapolitan schoolgirls cuddled together sharing their copy of Little Women in My Brilliant Friend. That’s when I bonded with the series. Just now I looked at Louisa May Alcott’s portrait card in the Authors deck. She’s shown in profile, a handsome woman in middle age, her gaze fixed as if on some distant prospect. Her expression is mild, as if she were picturing future readers like the girls in My Brilliant Friend.

If Alcott were thinking of her fellow author, Mark Twain, her gaze would likely darken, for she reportedly helped make sure that Huckleberry Finn was banned from the Concord Public Library, having once declared, “If Mr. Clemens cannot think of something better to tell our pure-minded lads and lasses, he had best stop writing for them.”

Twain and Jane

In the context of Emma Woodhouse’s observation that one half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other, I’ll close with Mark Twain, from an unpublished 1905 essay that eventually appeared in the Winter 1999 Virginia Quarterly Review: “Whenever I take up ‘Pride and Prejudice’ or ‘Sense and Sensibility,’ I feel like a barkeeper entering the Kingdom of Heaven…. Does Jane Austen do her work too remorselessly well? For me, I mean? Maybe that is it. She makes me detest all her people, without reserve. Is that her intention? It is not believable. Then is it her purpose to make the reader detest her people up to the middle of the book and like them in the rest of the chapters? That could be. That would be high art. It would be worthwhile, too. Someday I will examine the other end of her books and see.”