Born 111 Years Ago Today, William Burroughs Knocks on Our Door

By Stuart Mitchner

Let the devil play it!

—Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

The finale to Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, based on his song “Der Wanderer,” has been described as “technically transcendental” with a “thunderous” conclusion. It was also infamously difficult to play, so deviously demanding that Schubert himself reportedly threw up his hands during a recital and yelled “Let the devil play it!”

The finale to Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, based on his song “Der Wanderer,” has been described as “technically transcendental” with a “thunderous” conclusion. It was also infamously difficult to play, so deviously demanding that Schubert himself reportedly threw up his hands during a recital and yelled “Let the devil play it!”

I’m beginning this article on Schubert’s birthday, Friday January 31, looking ahead to the Wednesday, February 5 birthday of William Burroughs (1914-1997), who ventured into “Let the devil play it” territory when he linked the killing of his common-law wife Joan Vollmer to “the invader, the Ugly Spirit,” which “maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.” According to his introduction to Queer (Penguin 1985), Vollmer’s death during the drunken William Tell fiasco of September 6, 1951, opened the way to his breakthrough work Naked Lunch — if you believe him when he says he’d never have become a writer “but for Joan’s death.”

In a January 1965 Paris Review conversation reprinted in Writers at Work: The Third Series (Viking Compass), Burroughs frames the killing in the context of guns and gun violence in Mexico City, recalling it, as if offhandedly, “And I had that terrible accident with Joan Vollmer, my wife. I had a revolver that I was planning to sell to a friend. I was checking it over and it went off — killed her. A rumor started that I was trying to shoot a glass of champagne from her head, William Tell style. Absurd and false.”

He can’t say “I killed her” or even “it killed her.” Just “killed her.” The suggestion that “it just went off” is coming from a lifelong gun owner; witnesses at the scene not only agree about the William Tell scenario but remember Joan jesting just before the shot was fired: “I’m turning my head; you know I can’t stand the sight of blood.”

The Photograph

When I wrote about Joan Vollmer last month, I’d seen only two photographs of her: one resembling a college yearbook portrait, the other a snapshot by Allen Ginsberg in which she’s holding a bag of groceries; she appears conventionally attractive, with nothing in her expression to suggest someone capable of verbally holding her own with Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg or sitting up night after night with Burroughs listening while he held forth and holding forth herself while he listened, attentively, according to Kerouac, who describes “a very deep companionship that none of us would ever be able to fathom.”

On his site realitystudio.org, Jed Birmingham includes a photo of Joan in death that ran in La Prensa and other Mexico City papers. What makes the image so wrenching is how pretty she looks; there’s even a hint of amusement in her expression, as if she’d actually been making that wisecrack about the sight of blood when the bullet hit her.

Found in Rome

In the summer of 1960 I bought a beat-up Olympia Press paperback mistitled The Naked Lunch at a street market in Rome, marked down to $1 because pages 85 to 90 had been ripped out. Burroughs probably wouldn’t mind. The textual violation fits with his interest in the “cut-up” technique he describes to the Paris Review, admitting that subsequent books like Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded contain cut-up and folded-in texts from various authors, including Shakespeare, Joyce, Rimbaud, Kafka, Eliot, and Conrad.

The Missing Pages

As for the missing pages in my Naked Lunch, I just kept right on reading; no problem, because by then I considered the book little more than a collection of grossly amusing sketches I was already looking forward to sharing with my friends when I got home. When the U.S. edition appeared, I found that the missing section (no surprise) contained some of the most graphic episodes in a three-ring circus of sex, torture, and death. I figured I wasn’t missing much since I found most of it off-puttingly self-indulgent anyway, as Burroughs himself seems to admit (“the sex scenes were for my own amusement”); the “Ugly Spirit” was in evidence on every page of the savagely, brilliantly, unremittingly ugly tour de force that brought him fame, literary honor, and membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Passages like these also helped get the book banned in Boston, brought to trial, and eventually judged “not obscene” by the Massachusetts Supreme Court.

The truth is that in spite of the convoluted testimony for the defense by Norman Mailer, Allen Ginsberg, and others, Naked Lunch remains unapologetically obscene. The favored blurb on the covers of that and subsequent books by Burroughs is from Mailer (“The only American novelist living today who may conceivably be possessed by genius”). As Burroughs himself has said, what he was possessed by was “the Ugly Spirit” that accompanied the killing of his wife. And what must have truly impressed Mailer was that Burroughs had killed his wife and gotten away with it.

Before “Naked Lunch”

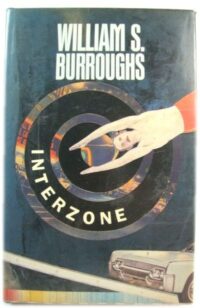

You get closer to the quiet painful truth of Burroughs and writing and death in “Lee’s Journal” from his pre-Naked Lunch collection Interzone (Penguin 1990). One passage begins, “Such a sharp depression. I haven’t felt like this since the day Joan died…What am I trying to do in writing? This novel is about transitions, larval forms, emergent telepathic faculty, attempts to control and stifle new forms.” What a contrast in tone to the obscene vaudeville to come starring A.J., “Last of the Bigtime Spenders” and the inimitable Dr. Benway (“Did I ever tell you about the time I performed an appendectomy with a rusty sardine can?”).

On the next page, Burroughs is even more explicit about the connection between Joan’s death and his own writing. Before September 6, 1951, he had “a special abhorrence for writing, for my thoughts and feelings put down on a piece of paper….This feeling of horror is always with me now. I had the same feeling the day Joan died; and once when I was a child, I looked out into the hall, and such a feeling of fear and despair came over me, for no outward reason, that I burst into tears. I was looking into the future then. I recognize the feeling, and what I saw had not yet been realized. I can only wait for it to happen. Is it some ghastly occurrence like Joan’s death, or simply deterioration and failure and final loneliness, a dead-end setup where there is no one I can contact? I am just a crazy old bore in a bar somewhere with my routines?”

“Word,” the third, final, and longest section of Interzone begins in the land of Naked Lunch, with a relatively tame preview of routines and cadenzas to come: “This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noise, farts and riot yipes and the slamming of steel shutters of commerce, screams of pain and pathos.”

Wait a minute. That cadenza has a familiar ring. Indeed, it reappears with minor adjustments a few pages from the end of Naked Lunch: The Restored Text (Grove Press 2001). Burroughs saved it to herald the end of his masterwork, as Schubert saved his Let-the-devil-play it cadenza for the last movement of the Wanderer Fantasy.

Burroughs begins his endgame movement: “Now I, William Seward, will unlock my word hoard…” And in the end, what are Burroughs’s cut-ups but variations on Schubert’s call for a satanic virtuoso to provide a cadenza worthy of the unplayable passage he himself had composed? No wonder Franz Liszt, the consummate cadenza virtuoso of the age, was not only fascinated and influenced by the Wanderer Fantasy but created his own symphonic variation.

Three Voices

Among the testimonials reprinted in Naked Lunch: The Restored Text, three are especially worth quoting. Lou Reed: “William Burroughs was the person who broke the door down.” Hunter S. Thompson: “William was a Shootist. He shot like he wrote — with extreme precision and no fear.” And Marshall McLuhan: “It is amusing to read reviews of Burroughs that try to classify his books as nonbooks. It is a little like trying to criticize the sartorial and verbal manifestations of a man who is knocking on the door to explain that flames are leaping from the roof of our home.”