Kafka at the Morgan — A Homebound Celebration

By Stuart Mitchner

Kafka in ecstasy. Writes all night long….

—Max Brod, October 1912

On April 13, the Czech migrant who has been residing at 225 Madison Avenue since November 22, 2024, will be leaving town. I’ve had almost four months to visit the Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibit commemorating Franz Kafka’s June 3, 1924 death and yet here I sit in my study with a copy of Diaries 1910-1923 open to a facsimile of the undated first page, which begins with a single sentence: “The onlookers go rigid when the train goes past.”

On April 13, the Czech migrant who has been residing at 225 Madison Avenue since November 22, 2024, will be leaving town. I’ve had almost four months to visit the Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibit commemorating Franz Kafka’s June 3, 1924 death and yet here I sit in my study with a copy of Diaries 1910-1923 open to a facsimile of the undated first page, which begins with a single sentence: “The onlookers go rigid when the train goes past.”

At home, I can see the German sentence in Kafka’s handwriting and know what it says thanks to the English translation on the facing page. At the Morgan, while I’d be in the presence of the actual notebook, it would be under glass, as would Kafka’s unintelligible handwriting, the room would be crowded, and I would be distracted by the metropolitan rush of my first walk in the city since the October 2019 J.D. Salinger centenary at the New York Public Library.

“The Judgment”

What’s been holding me up? Along with the raw winter weather, and feeling estranged from the city I’ve known and loved since I was 10, I also feel estranged from the story that the exhibit commentary calls Kafka’s “literary breakthrough.” In effect I’m standing outside the gates of the Centenary Castle, unable to provide the password that would prove my understanding and appreciation of “The Judgment.” I was a 20-year-old college senior the first time I read the story and to say I didn’t “get it” would be a gross understatement. The moment at the end when the father calls the son “a devilish human being” and declares “I sentence you to death by drowning” was more of a shock to me than the giant-insect weirdness of the opening sentence of The Metamorphosis. Still living at home with my parents, with my thoughtful father’s fire-engine-red Buick convertible at my disposal every night, the proto “magic realism” of the demented judgmental father and the devoted son immediately, unthinkingly, literally obeying the absurd pronouncement seemed as incredible as, say, the thought that by allowing me to drive his flashy, high-powered car my father had sentenced me to death by driving.

Max Brod’s Gift

I found my “password” in Franz Kafka: Diaries 1910-1923 (Shocken 1976, 25th printing), edited by Max Brod and translated by Joseph Kresh and Martin Greenburg, with the cooperation of Hannah Arendt. Every reader who values the diaries should give thanks to Brod for ignoring Kafka’s command to burn all his unpublished work. For a start, imagine being deprived of the September 23, 1912 entry:

“This story, ‘The Judgment,’ I wrote at one sitting during the night of the 22nd-23rd, from ten o’clock at night to six o’clock in the morning. I was hardly able to pull my legs out from under the desk, they had got so stiff from sitting. The fearful strain and joy, how the story developed before me, as if I were advancing over water. Several times during this night I heaved my own weight on my back.”

Brod’s phrase “Kafka in ecstasy” can be felt in the rush of impressions that follow: “How everything can be said, how for everything, for the strangest fancies, there waits a great fire in which they perish and rise up again. How it turned blue outside the window. A wagon rolled by. Two men walked across the bridge. At two I looked at the clock for the last time. As the maid walked through the anteroom for the first time I wrote the last sentence. Turning out the light and the light of day.” Later in the entry, Kafka admits “Only in this way can writing be done, only with such coherence, with such a complete opening out of the body and the soul.”

Another Death Sentence

Imagine Brod reading this entry with the fate of the diaries in his hands after Kafka had sentenced them to “death by fire.” Imagine his response to the reference to “the great fire” in which “the strangest fancies perish and rise up again,” not to mention the phantom touch of this passage from 1910, among the first in the diary: “there was always something in me to catch fire, in this heap of straw that I have been for five months and whose fate, it seems, is to be set afire during the summer and consumed more swiftly than the onlooker can blink his eyes.”

Still at Home

I almost made the trip to the Morgan last week, on a dry, windy, suddenly summery Saturday. Instead, I stayed home, fresh from reading “The Judgment” with the Diaries once again open to the first entry. Having Joseph Kresh’s translation on my desk gave me time to appreciate the way “The onlookers go rigid when the train goes past” presages the story’s closing sentence — “At this moment an unending stream of traffic was just going over the bridge.”

The sentenced son had rushed “across the roadway, driven towards the water,” grasping at the railings “as a starving man clutches food,” swinging himself over, “like the distinguished gymnast he had once been in his youth, to his parents pride,” thinking “Dear parents I have always loved you, all the same” as he lets himself drop, aware of a motor bus coming which would easily cover the noise of his fall.”

The life-goes-on poetry of passing train, approaching bus, and “unending” traffic would have been lost to me to me in the museum, even though I might have been gazing at the notebook actually containing the full first draft of the story that Kafka wrote into the preceding pages of the diary, which I have close at hand in Ross Benjamin’s 670-page “complete, uncensored” edition of the Diaries (Schocken 2022). I mentioned Kresh’s translation just now because I prefer “The onlookers go rigid when the train goes past” to Benjamin’s “The spectators stiffen when the train passes.” I’m also wondering about Benjamin’s translation of the diary version of the last sentence of “The Judgment” — “At that moment a positively endless stream of traffic was going over the bridge.” Did Kafka himself remove that unnecessary “positively”? Or was it Benjamin’s addition?

The Crowded Desk

Look at this desk. There’s barely room for the computer keyboard. In fact, Benjamin’s tome just fell on the floor, narrowly missing my left foot. Perched precariously on top of my old Modern Library edition of Selected Short Stories translated by Edwin and Willa Muir is Stanley Corngold’s invaluable Expeditions in Kafka (Bloomsbury 2023). (Like Chekhov’s gun, Corngold’s book has to go off at the end of the article, primed with the bullet of a quote.) Meanwhile, tucked into a corner under the shelf containing a photograph of my smiling 35-year-old father with our Siamese cat in his lap is a circa 1920s guide to Prague whose large colorful map shows me the river and the bridge of the story, plus the street where Kafka and his family lived from 1907 to 1913, on the top floor of the house “Zum Schiff.” According to Benjamin’s italicized addition, Kafka called the street “the approach road for suicides.”

Enter Andersen and Zola

In short, I have everything I need here at home except the Morgan, which would never fit on my desk, unless it were in a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, who was born on this day, April 2, in 1805. On the large table within easy reach on my right is a copy of the Tales of Grimm and Andersen with an introduction by W.H. Auden. Next to it is Michael Rosen’s The Disappearance of Emile Zola: A Story of Love, Literature and the Dreyfus Case (Pegasus 2017). Zola became Andersen’s April 2 birthmate 35 years later in 1840.

What have these two to do with Franz Kafka? You might as well ask what do extraordinary transformations and Dreyfus scandal antisemitism have to do with the author of The Metamorphosis and The Trial.

Corngold’s Gun

Stanley Corngold has given me the closer I need even though I used the same irresistible line a year and two months ago in my column on Expeditions in Kafka. Referring to Kafka’s “relevance to the flows of (forever) current life,” Princeton’s professor emeritus offers this “pandemic-appropriate” advisory from Kafka’s Dearest Father: Stories and Other Writings: “There is no need for you to leave the house. Stay at your table and listen. Don’t even listen. Just wait. Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked, it can’t do otherwise; in raptures, it will writhe before you.”

———

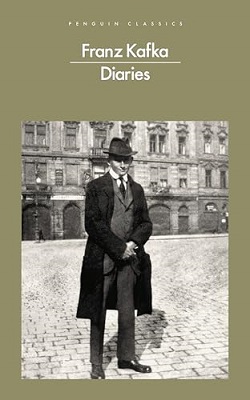

For information about the Kafka exhibit, which runs through April 13, visit themorgan.org/visit or contact tickets@themorgan.org. The cover image of Kafka on the Altstädter Ring in Prague shown here also appeared with the Morgan’s full-page ad in the December 5, 2024 issue of The New York Review of Books. Besides celebrating Kafka’s centenary, the Morgan Library is celebrating its 100th anniversary as a public institution.