On Lincoln’s Birthday — What a Play Shakespeare Might Have Written

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) knew Shakespeare by heart. It wasn’t just that he could recite long passages from Hamlet and Macbeth and Richard III, or that he felt compelled to regale friends, associates, and secretaries with lengthy impromptu recitations, even in the White House. “By heart” is no mere figure of speech. The Bard was in his blood, and he knew when the speeches he loved had been violated or omitted, as was sometimes the case with the king’s soliloquy in Hamlet (“O, my offence is rank”) or with the glorious duel of invective between Falstaff and Hal in scene 4, act 2 of the first part of Henry IV, which was dropped altogether during a performance the president attended in March 1863.

One-hundred and fifty years ago today Lincoln turned 55. That his February 12 birth date falls in close proximity to a high-profile ceremony honoring the profession of acting — he who loved Shakespeare and died in a theater at the hands of an actor — is one of those coincidences poets, fatalists, and columnists enjoy taking note of; the same could be said of the fact that less than two weeks after Lincoln’s 154th birthday, the Best Actor Oscar went to Daniel Day Lewis for his performance in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. Lewis, it’s clear, knew Lincoln “by heart,” having admitted “never, ever” feeling the same “depth of love” for a human being that he’d never met. Lincoln, he went on, probably has that effect “on most people that take the time to discover him.”

Last Days

This year the untimely February 2 death of Philip Seymour Hoffman will likely be acknowledged on Oscar night, as was Heath Ledger’s, also a month before the ceremony, in 2008.

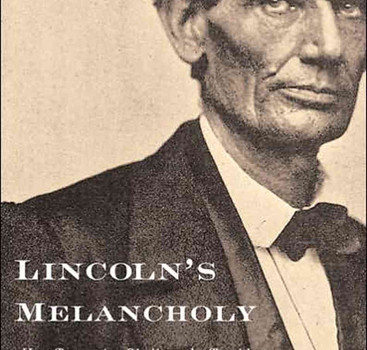

As I write, the front section of the February 6 New York Times is on my desk along with Joshua Wolf Shenk’s book, Lincoln’s Melancholy (2005); a 1904 collection of Lincoln’s Letters and Addresses; and a copy of Alec Wilkinson’s book-length profile of Pete Seeger, who died January 27. The Times is open to an article tracking Hoffman’s movements from place to place in New York (“A Complicated Actor in His Last Days”), playing with his kids in a Village playground, leaving the 92nd Street Y, landing strung out, looking like “a street person” at LaGuardia, having a four-shot espresso at Chocolate Bar, eating dinner at Automatic Slim’s, withdrawing cash from an A.T.M. at D’Agostinos. These glimpses of the actor — possibly the most familiar face on the screen for fans of sterner stuff than action blockbusters and tasteless comedies — going about his business in a familiar locale gave me a clearer sense of his stature, particularly in the way the desperate, driven, often unattractive roles he frequently played were reflected in the various eye-witness accounts of his appearance in those last days.

Sympathy for Seeger

It’s hard to resist remarking the contrast between Hoffman dying alone in New York and Pete Seeger, a beloved folk legend, dying in his nineties surrounded by family and remembered with a two-page obituary in the Times. On the Guardian tribute site someone who had seen Seeger at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall in 1967 wonders “Was this what it had been like to see Abe Lincoln speak? Seeger’s presence was simultaneously joyous and calming. His words, both spoken and sung were an absolute balm.” The more I read by and about Lincoln, particularly in Lincoln’s Melancholy, the less I can see in common between the man whose favorite Shakespearean play was Macbeth and the man who wrote “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.”

Reading Alec Wilkinson’s balanced profile of the singer, however, you find another, refreshingly less Lincolnesque Seeger. It’s hard not to like someone who can make fun of his skills as a carpenter, telling Wilkinson, “I put up some shelves to hold records and books right here, and the baby’s crib was under it. One night we heard a terrible crash, and the shelf and all the books and records had come down on her crib ….That’s the kind of stupid thing I’ve done all my life.”

You’re on Seeger’s side again when you read the transcript of his testimony during the HUAC hearings in 1955 when he took the first amendment rather than cowering in the fifth and went briefly to jail for it.

But in the context of Lincoln’s tendency for brooding and self-doubt, what most struck me about the coverage of Seeger’s death, also in connection with the coverage of Hoffman’s last days, was Jesse Wegman’s January 28 op-ed piece about Seeger protege Phil Ochs’s last night. The theme is “being there” for someone in distress. Nobody was there for Hoffman, though judging from an article in this Sunday’s Times (“His Death, Their Lives”), it’s touchingly apparent that the actor who died alone at night “with a needle in his arm” had been an inspiration to numerous others struggling with addiction. According to what Neil Young told Wegman, Seeger never forgave himself for not being there for Phil Ochs on an April night in 1976. Seeger had been in the city and was late for the train home to Beacon, an hour up the river. Ochs was in trouble, had been depressed and drinking heavily for a long time “and had reached out to Pete. ‘He really wanted to talk.’” Seeger had to choose between staying in the city to be with Ochs and taking the train home. To his lifelong regret, he’d taken the train. Ochs hanged himself that same night and “for 37 years the decision to leave that night ate at Pete.”

Brother’s Blood

Unlike you gentlemen of the profession, I think the soliloquy in Hamlet commencing “O, my offence is rank” surpasses that commencing “To be, or not to be.”

—President Abraham Lincoln,

17 August 1863

Lincoln was writing to the actor James H. Hackett, who had played Falstaff in the compromised version of Henry IV the president had seen some months before. Though he was writing to acknowledge receiving a copy of Hackett’s self-touting book on Shakespeare, he took the occasion to mention his favorite plays, with, again, Macbeth the most admired (“It is wonderful”). Meanwhile he neatly avoided mentioning his disappointment in a production that left out his favorite part, writing, “The best compliment I can pay is to say, as I truly can, I am very anxious to see it again.” When Hackett quoted Lincoln’s letter in a publicity broadside that generated negative press, the president responded more than graciously with a note saying that he’d “not been shocked by the newspaper comments” because such comments “constitute a fair specimen of what has occurred to me through life. I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule.”

Even as he was exercising his inner Shakespeare with the word play on malice, ridicule, and kindness in early November 1863, Lincoln was looking forward to the speech he would deliver at the dedication of the Gettysburg national cemetery later that month. No wonder, then, that he would favor the more fitting “offence is rank” soliloquy by the fratricidal Claudius, with its reference to “the primal eldest curse” of “a brother’s murder,” to “a man to double business bound,” to a hand “thicker than itself with brother’s blood,” and to the question, “Is there not rain enough in the sweet heavens to wash it white as snow?”

Looking for some mention of Lincoln’s 55th birthday in my 110-year-old edition of his letters and speeches, I found something from January 7, 1864, written on a letter from the governor of Ohio “regarding the shooting of a deserter on that day.” Lincoln calls the case “a very bad one,” since before receiving the governor’s message, the president had ordered the man’s “punishment commuted to imprisonment … at hard labor” for the duration of the war, “and had so telegraphed.” Lincoln explained the failed act of mercy in these words: “I did this, not on any merit in the case, but because I am trying to evade the butchering business lately.”

“The Greatest General”

The photograph of Lincoln used by Shenk for the cover of Lincoln’s Melancholy was taken in 1860, a year before he became president. The troubled expression on Lincoln’s already careworn face bears out Shenk’s subtitled premise (How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness). In a prelude, Shenk recounts the story Leo Tolstoy told a reporter a year before he died. Having found himself the guest of a Caucasian chief of the Circassians “living far from civilized life,” he was telling the chief and his “wild looking riders … and sons of the wilderness” about the Czars and the greatest military leaders, with particular emphasis on Napoleon. They were duly fascinated but they wanted more. What about “the greatest general and greatest ruler of the world,” the man whose name was Lincoln.” Tolstoy accordingly told them of Lincoln “and his wisdom, of his homelife and youth,” But they wanted to know more, “his habits, his influence upon the people and his physical strength,” surprised to hear that he “made such a sorry figure on a horse.” Finally they asked for a photograph of this hero who “spoke with a voice of thunder” and was “so great that he even forgave the crimes of his greatest enemies and shook brotherly hands with those who had plotted against his life.” To find a photograph, Tolstoy went to the nearest town with one of the young riders. As he handed the picture to him, Tolstoy was impressed by “the gravity of his face and the trembling of his hands” as he gazed” for several minutes silently … deeply touched.” Asked what had so moved him, the young man pointed out that Lincoln’s eyes are “full of tears and that his lips are sad with a secret sorrow.”

Tolstoy no doubt embellished the moment, for he was as starstruck as the Circassians, telling the reporter that of all the great national heroes and statesmen of history, Lincoln was the only real giant … a saint of humanity whose name will live thousands of years in the legends of future generations.”

What a play Shakespeare might have written about such a man.