Shakespeare in America: A Tale of Two Stratfords on Paul Robeson’s Birthday

By Stuart Mitchner

In his introduction to Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now (Library of America $29.95), James Shapiro writes of the “steady stream of American tourists” visiting the Bard’s birthplace, Stratford-Upon-Avon, among them “a pair of future presidents,” John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. According to Abigail Adams, Jefferson “fell upon the ground and kissed it” while her husband cut “a relic” from a chair said to have belonged to the poet himself.

Although legions of tour busses may never be a fact of life the way they are in Shakespeare’s home town, Princeton is something of an American Stratford for people coming to pay their respects to Albert Einstein, who lived the last half of his life here, and Paul Robeson, who was born here on this day, April 9, in 1898, and spent the first nine years of his life in the Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood, Jackson having been at one time the street now known as Paul Robeson Place.

A Realm Unto Himself

The many facets of Paul Robeson’s genius — as a speaker, athlete, singer, actor, and world figure like his friend Einstein — led the PBS series, American Masters, to refer to him as “the epitome of the 20th-century Renaissance man.” Shakespeare, who wrote the signature role of Robeson’s acting life. is beyond terminology. There’s no end to him, or to it, if you believe that no single human being could have created what he created, a vast, complexly intelligible realm that will always be there to be discovered, explored, inhabited. “Reading Shakespeare continues to bless us, long past the first encounter,” says another former president, Bill Clinton, in his foreword to Shakespeare in America. Clinton entered the realm when an English teacher in Hot Springs, Arkansas had him memorize a hundred lines from Macbeth (“I was not overjoyed”) from which he learned an early lesson about “the perils of blind ambition and the emptiness of power.”

Paul Robeson was introduced to Shakespeare in 1915 by an English teacher at nearby Somerville High School. According to Martin Duberman’s 1988 biography, the 17-year-old senior, one of 12 African American students, played the Moor in a burlesque version of Othello. His teacher “later recalled her hesitation in asking him to take on the parodic role of Othello as a hotel waiter, since the performance was designed to raise money for a class outing to Washington, D.C.,” which Paul could not have attended “because no hotel in the capital would accept a black guest.” Even so, he played the part and “proved a huge hit with the audience.”

Although he seems to have been popular with his white classmates, Robeson was aware of a more subtle version of prejudice in high school society that, as Duberman points out, “allowed him through practice and forewarning, to keep his temper under wraps.” A teacher who called him “the most remarkable boy I have ever taught, a perfect prince” still “can’t forget that he is a Negro.” It was Robeson’s understanding of the social reality, of always knowing his “place,” that sustained his popularity. The situation suggests a microcosm of his later career. Even when turning in superior performances, whether as speaker, athlete, singer, or actor, he had to “exhibit maximum affability and minimal arrogance.” Whenever whites were “surpassed” by him, his attitude could “never smack of triumph.” Duberman quotes Robeson repeating “a litany drummed into him by his father, ‘do nothing to give them cause to fear you.’”

Consider how it must have been for a man conditioned to downplay his power finding himself in a realm of language as rich as Othello, peering into the mirror Shakespeare held up to him as he assumes the character of a black general, a leader of men. Othello’s first great speech (Act 1, scene iii) is one that Robeson must have been thrilled to perform, the way it brings the actor and the character together as Othello discourses on his success as a performer disarming Desdemona with stories like those he dazzled her father with, moving her to tears “when I did speak of some distressful stroke/That my youth suffer’d,” recalling how she “gave me for my pains a world of sighs:/She swore, in faith, ‘twas strange, ‘twas passing strange;/’Twas pitiful, ‘twas wondrous pitiful.” Describing how Desdemona “wish’d/That heaven had made her such a man,” and if the Moor could but teach a friend how to tell his tale, it “would woo her,” he shows that the “witchcraft” he used to seduce her was simply a matter of stepping forth as the hero of his own story: “She lov’d me for the dangers I had pass’d/And I loved her that she did pity them.”

The speech about the wooing of Desdemona also gave Robeson the ammunition he needed to woo and win audiences at the play’s start, creating a bond that assured his power over them even through the climactic moment. It was there that Margaret Webster, the director of the triumphant 1943 New York production, felt that he fell short, unable to convincingly summon up the full measure of rage that would have shaken the theatre and filled Desdemona with mortal terror — Robeson being, remember, the man who grew up repeating the survivor’s mantra “Do nothing to make them fear you.”

Webster, who also played Emilia, Iago’s wife and Desdemona’s confidante in the same production, had hoped that Robeson would be able to bring “his anger over racism onto the stage with him,” but “he could not recapture it.” In the turbulent final scenes he “never matched at all the frenzy and passion the role called for.” Robeson himself “acknowledged that he had trouble unearthing his rage on demand,” because “he had been brought up, as a survival tactic, to keep it carefully interred”

Triumph and Tragedy

Robeson has a chapter to himself in Shakespeare in America titled “Paul Robeson’s Othello,” which consists of an ecstatic, topically resonant, politically driven notice in the Leftist journal, The New Masses, by Samuel Sillen, “a prominent figure in the Communist literary movement of the 1930s and 1940s.” It’s clear that though he’s sounding the party line, Sillen is genuinely moved by Robeson’s “indescribably magnificent” performance; nevertheless, his rhetoric reveals where he’s coming from when he calls Robeson “the greatest people’s artist of America” and the performance “an epochal event in the history of our culture.”

Given what would befall Robeson in the decade ahead, the reference to the “people’s artist” is galling, as is the partisan drumbeat that ends the “review” (by now you definitely feel the need to put that word in quotes): “We treasure the event. We mark it as a birthdate. We carry on from here, lifted by Paul Robeson to a height from which new and vast horizons of a creative people’s culture endlessly unfold.”

Robeson followed that drumbeat to his fate, which Sillens inadvertently forecasts in his reference to Othello as “a play primarily of a vast human injustice” where “Othello’s injustice to Desdemona is only a part of the great injustice that has been done to him and in which he himself has unwittingly collaborated.”

Always a Challenge

Trying to follow the last 25 years of Robeson’s life (he died on January 23, 1976) is disheartening, what with all the well-meaning, self-confounding moves he made, the exploitations and the betrayals, the black-listers and witchhunters smearing his name in the consciousness of the American public and contributing to the state of mind that led to a breakdown and a suicide attempt. Duberman’s biography concludes by observing that when he died, the white press “after decades of harrassing Robeson now tipped its hat to a ‘great American’” while discounting “the racist component central to his persecution” and ignoring “the continuing inability of white America to tolerate a black maverick who refused to bend.” Meanwhile, the black American press provided editorials depicting a “Gulliver among the Lilliputians” and a life “that would always be a challenge and a reproach to white and black America.”

Home to Stratford

In 1959, when Robeson was 62 years old, he returned to Shakespeare’s roots in Stratford to play Othello in Tony Richardson’s gimmicky production of the play at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. His Desdemona, 26-year-old Mary Ure, was told to play Othello’s wife “as if she were acting in an Arnold Wesker kitchen-sink drama.” According to Duberman, Richardson filled the stage “with splashy special effects that called maximum attention to his own lively powers of invention” and that were clearly at odds with Robeson’s “gravity and reserve.”

In the end, Robeson carried the day, as the “critical majority succumbed to the authority of his stage presence.” Othello sold out its seven-month run immediately, and on opening night, the audience gave Princeton’s native son 15 curtain calls.

Last month Princeton celebrated Einstein’s birthday with a community event full of fun and fondness for an adopted local icon. This past Sunday Paul Robeson’s birthday was celebrated in the building named for him with a screening of Show Boat. Our Stratford honors two of the giants of the previous century, mythic figures both, but of the two, the largest, most tragic, and most truly Shakespearean is Paul Robeson.

The Princeton Public Library has a large Robeson component in its collection, which includes Martin Duberman’s Paul Robeson (Knopf 1988) and Paul Robeson Jr.’s The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898-1939 (Wiley 2001).

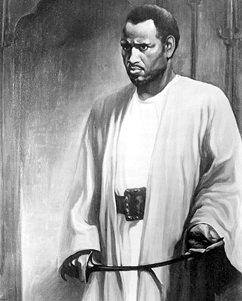

The painting of Paul Robeson as Othello in the 1943 production, still the longest running Shakespeare play in Broadway history, is by Betsy Graves Reynau (1888-1964).