Robert Desnos, Henri Rousseau, and “A Cat Like Nothing Else on Earth”

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

There’s a rapping at my study door, a soft persistent tapping, with a hint of claw in the sound. The door is gently banging back and forth in the frame as I sort through ideas for a May 28 column. When the rapping intensifies, it inspires thoughts of a famous Raven at a famous chamber door. Even in the age of Rap the word “rapping” belongs to Poe.

Waiting on the other side is Nora, our glossy 11-year-old tuxedo cat who can’t abide closed doors. I put my thoughts on hold and clear a space for us amid the jumble of books piled on the chaise by the window. Stepping lightly over the rocky paperback-hardback terrain until she has a clear view of the street below, Nora casts a watchful eye on the commotion of a garbage truck making the Thursday pick-up. No birds or squirrels being in sight, she turns her attention to a battered paperback anthology of French poetry I found at the Cranbury Book Worm the other day, gives it a whiskery nuzzling, and then puts one white paw on Baudelaire: His Prose and Poetry, as if to say, “This is mine.” Then she curls up by my side and, as my maternal grandmother would say, commences purring.

With my free hand, I open the Baudelaire, a severely creased Boni & Liveright Modern Library edition from 1919, and start reading aloud from a prose poem about twilight madness and a man who would be sociable and indulgent during the day and “pitiless” in the evening, having once thrown at a waiter’s head “an excellent chicken, in which he imagined he had discovered some insulting hieroglyph.”

While I’m not suggesting that our Nora has a soft spot for Baudelaire, I can tell you that her ears perked up when I read the last part, she who in her wild youth performed feats equal to the throwing of chickens at waiters, if not the throwing of waiters at chickens. Remember that Baudelaire himself was partial to a “strong and gentle” cat, “the pride of the house,” beloved of “ardent lovers and austere scholars” and worthy of comparison to “the mighty sphinxes” with “particles of gold spangling their mystic eyes.”

In fact, it was “The Cat Like Nothing Else On Earth,” a poem by Robert Desnos, that took me to the Cranbury Book Worm and the paperback anthology of French poetry I’m reaching for when the “pride of the house” decides she’s had enough, slips off the chaise, and heads for the door.

The Book Worm

In its heyday, when it occupied the most imposing house on Main Street, the Book Worm had well over 100,000 volumes in stock, not to mention stacks of old Life magazines, LPs, CDs, DVDs, posters, paintings, and upstairs, along with more rooms of books, a substantial assortment of antiques — and fresh vegetables. Here, surely, was the only bookstore in the world that sold cucumbers and tomatoes grown in the mulch made from a compost heap of decaying books. Sadly, the Worm has been downsized to a shadow of its former self and installed in a cramped store front a block away, but as the Stones will tell you, while you may not always get what you want, if you try, sometimes you get what you need. I got Robert Desnos (pronounced Dez-nose) and Henri Rousseau.

Gateway to Rimbaud

Given the condition — spine cocked, page ends yellowed — Wallace Fowlie’s bilingual 1955 Grove Press paperback, Mid-Century French Poets, should not be priced at $6. The catch is that it’s inscribed “Wishes to Marion and Francis for a blessed Xmas, love Wallace 1955.” Francis is Francis Fergusson, the author of Idea of the Theater (Princeton 1949), who taught at Rutgers, lived in Kingston, died at Princeton Hospital in 1986, and sublet our house in Bloomington one summer; on the subject of inscriptions, the Fergusson kids wrote their names in pencil on the wall of the closet in my room, and so did Leslie Fiedler’s kids when the author of Love and Death in the American Novel sublet the house for a year.

As for Fowlie, he was nothing less than the gateway to Rimbaud for Jim Morrison and Patti Smith. His translation of the Works is on my desk even now. He also wrote a book about Rimbaud and Jim Morrison called The Rebel as Poet, and his friendship with Henry Miller resulted in the publication of their correspondence.

With inscriptions and associations like that, and a nice selection of Desnos inside, how could I not buy this book?

Rousseau’s Dream

My other purchase at the Book Worm was a Museum of Modern Art monograph from 1946 about Rousseau (1844-1910), who was born on May 21 and might have been the subject of last week’s column if he hadn’t been competing with Fats Waller.

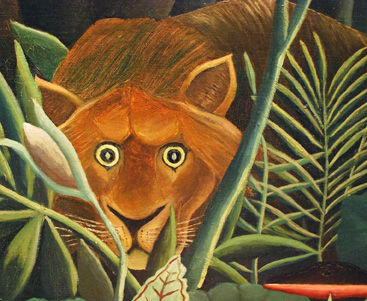

The reproductions in the Rousseau book are all in black and white, like Nora, and when she shows up again, nuzzling the leg of my desk, it happens that I’m gazing at a full-page detail of two wild felines prowling the dense forest in Rousseau’s The Dream, painted the year he died. As the title suggests, these creatures are moving wide-eyed and bewildered through the dreaming mind of the naked damsel on the couch. In the poem he attached to the painting, the painter imagines her listening to a snakecharmer’s flute. He’s given her face a stern touch of attitude, thinking perhaps of Léonie, the fiftyish widow with whom he was hopelessly in love at the time. Léonie worked behind the counter in a Paris department store Rousseau faithfully visited only to be unceremoniously rebuffed by her. Day after day, he would return home to paint himself deeper into The Dream. Same old story, he does it all for Léonie, leaves her paintings in his will, and she can’t be bothered to go to his funeral.

The Cat

Robert Desnos wrote “The Cat Like Nothing Else on Earth” for artists and dreamers everywhere, including of course, Le Douanier, the former toll collector eating his heart out over a department store sales clerk. Desnos’s phenomenal cat goes to a doctor who listens to his heart and tells him it “isn’t doing well/It’s like nothing else on earth.” Then he goes to see “his lady, who examines his brain,” and tells him, “Your brain’s not doing well/It’s like nothing else on earth.” As if that isn’t enough, she adds, “It’s unlike anything in the whole world.” The poem ends with a sigh: “And that’s why the cat like nothing else on earth/Is sad today and doesn’t feel so well.”

Of all the photographs of 20th century painters I’ve ever seen, none come as close to capturing the spirit of “The Cat Like Nothing Else” as the one of Rousseau taken in his studio on December 14, 1908. The aging painter sits facing the camera, his elbow on a table, his chin propped on his hand, looking as if he’s just shuffled home after another slap in the face from Léonie, the muse from hell. Home is one room with a large window. There’s a violin on the table, a broom in the corner, lots of pictures on the wall, and somewhere out of camera range, the artist’s paintings, his easel and the usual accoutrements of his true profession. When someone asks him isn’t it uncomfortable to sleep in a studio, he says, “When I wake up I can smile at my canvases.”

At least he’s got company. On the floor near the broom there’s a bowl of milk.

Desnos Cheats Death

When Robert Desnos died on June 8, 1945, at the concentration camp in Terezin, Czechoslovakia, it was from typhus. Some time before he fell ill, he and a group of other internees were being marched to the gas chamber, so the story goes, when Desnos suddenly began reading the palms of the condemned, predicting a long full life for everyone. His manner was so convincing, so dismissive of all earthly doubt, that the victims began to believe him, and the guards became confused, lost touch with their mission, and ordered the people back into the truck, which took them back to the barracks.

If this anecdote sounds far-fetched, there are indications throughout Wallace Fowlie’s biographical sketch that if anyone could have performed such a feat, it was Desnos, who grew up believing in the existence of the marvellous and the exotic. In the 1920s he hung out with the surrealists, the only one “who could speak surrealistically at will,” according to André Breton; he “read in himself as in an open book,” practiced automatic writing, and seemed to “live within poetry.” During the sleep seances the others engaged in, Desnos proved to be the only genuine medium. As soon as he was asleep, “his power of speech was released and flowed abundantly.” He had discovered a way of translating himself into poetry without the help of books, without the need of writing, “in a state of constant inspiration.”

During the occupation of Paris, Desnos joined the Resistance and helped direct the underground publications of Les editions de Minuit, until he was arrested by the Gestapo and taken to Auschwitz, then Buchenwald, and finally Terezin.

———

There’s that tapping at the study door. It’s after 2 a.m. and the Cat Like Nothing Else On Earth is waiting to be let in.

I have a friend from days on the road to thank for introducing me to Desnos and “The Cat Like Nothing Else On Earth.” This morning he sent me a poem he just finished, “The Shade of Robert Desnos,” which can be read on rogeryates.blogspot.com, at the top of a monthly roster of poetry very much worth scrolling through.